I’ve never seen anything like The Stunt Man. There will never, ever be another movie quite like The Stunt Man. This film has a very unique tone that is nearly impossible to pin down. It’s a satire of Hollywood. It’s a romance. It’s a drama. It’s a break-neck action picture. It’s a madcap comedy. This film is so many things, but most importantly, it has a wildly distinct personality, feeling like a film that just HAD to be made by the person who made it. The Stunt Man isn’t even really a film – it feels more like a carnival of ideas and action, totally off the reservation, made with a jocular style that has moments of peculiar beauty, and featuring performances that just have to be seen to be believed. There’s a raggedy quality to the film, an “in-progress” ambience that befits the movie-within-a-movie structure of the story, and the freewheeling style allows for much self-reflexivity on the part of Rush and his team of craftsmen. A notoriously tortured production, The Stunt Man has taken on the label of “lost classic” over the years, and it’s a film that many people probably have seen a long time ago but have fuzzy memories of now. It’s absolutely worth a revisit and reconsideration, if for no other reason that something this singularly bizarre and eccentric should be discussed more often than the generic, franchise-able crap that so often litters our multiplexes.

The Stunt Man, which was released in 1980, was adapted for the screen by Rush from Paul Brodeur’s novel, and centers on a Vietnam veteran named Cameron (Steven Railsback in an emotionally wild performance of astonishingly broad range) who has an run-in with the cops, flees, and accidentally ends up on the set of a big-budget WWI movie that’s being filmed on a near-by beach by a flamboyant and utterly tyrannical director named Eli (Peter O’Toole in a massively entertaining wink-wink performance) who hides the man under the guise of being a stuntman on his picture, who he then uses in a series of outlandish and death-defying set-pieces, sometimes without his participant’s full knowledge of all of the rules. Cameron can’t help but fall in love with the film’s leading lady, Nina (Barbara Hershey, sexy and funny), whose romantic past with her director causes Cameron to become a tad unhinged.

Cameron also starts to realize that his potentially insane boss has made it a habit of pushing his previous stunt-men to their limits, with possibly deadly results. Will Cameron’s cover be blown? Will he survive the increasingly crazy film production? Will he and Nina be able to live happily ever after? Cameron’s life starts to bleed from reality to fantasy and then back to reality, sometimes within the same scene, as Eli continues to press on in the most insane of manners, creating hostility between him and his crew, his actors, and pretty much everyone around him. Then the day comes for the film’s climatic action scene to be shot, and Cameron isn’t sure if Eli is out to sabotage him in an unsuspecting way, or if he’s just doing everything all in the name of cinema and for the perfect shot.

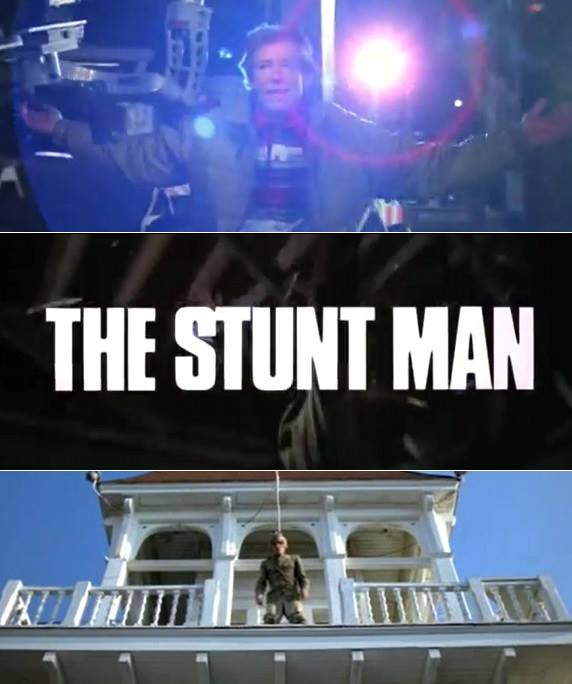

Rush was a filmmaker who understood the idea of madcap comedy better than most, and in The Stunt Man, he brought a level of gonzo energy to the film’s multiple action sequences, which, simply put, are all fabulous to observe and dissect. If you’re going to call your movie The Stunt Man you better have some great stunts to show off, and I just don’t understand how people weren’t killed while making certain sequences of this hilariously over the top film. One bit in particular, with Railsback running along the sides of houses and over roof-tops while planes are flying overhead and soldiers are firing rounds at him and jumping on him from all angles – it’s berserk, it’s hysterical, it’s all totally over the top, and finally amazing. No blue screens, no CGI, all real stunt work, with people crashing through balsa wood and sugar glass. This is a film that is all about the art of deception, and how cinema has the ability to lie to us yet make it look real and honest.

The Stunt Man also has a casual vulgarity that I just loved, with out of the blue nudity, random bits of seemingly improvised dialogue, a ton of looped audio that unintentionally ramps up the odd humor, and a general sense of anything goes/anything can happen which keeps the film hurtling along with a sense of unpredictability that is rarely matched. And then there’s the truly insane ending, with the film’s credits rolling while one of the actors is still talking, trying to make sense of his situation, and it’s like Rush is saying to everyone, himself included: “Hey, it’s just a movie.” Because Rush was attempting to bite off SO much with this effort, it feels like his ultimate “kitchen sink” film, something he made as if he were never going to direct a film again, cramming it with as many ideas and obsessions as he possibly could.

And that was sort of the case. After sitting on the shelf for over a year due to a lack of completion funds, 20th Century Fox bought the film, but Rush ended up battling it out with the studio over a botched release, despite the film being nominated for Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor for O’Toole. It then took Rush 14 years to return to the director’s chair (he was fired off of 1990’s Air America, for which he wrote the original script) for the ill-fated erotic thriller Color of Night, which became infamous as “that movie where Bruce Willis felt the need to show the world his bellend.” It’s a shame that Hollywood loves to forget about genuine voices like Rush, and Martin Brest, and Michael Cimino, filmmakers who were interested in telling stories outside of the cookie-cutter norm, guys with too much of an idiosyncratic view and style for the studio bean-counters.