![1200[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/120011.jpg?w=685)

The cinema of M. Night Shyamalan has always been marked through thick and thin by the embrace of warmth where exploitation and cynicism would simply be an easier alternative. With one foot planted firmly in reality and the other in the prospect of paranormal phenomena (and even more specifically, its application in our daily lives), the Philadelphia native’s latest endeavor is simultaneously a sign of purest artistic reinvigoration and a most welcome return to form; magnificently erratic form at that, and most remarkable of all is how the man who was once dubbed “The Next Spielberg” balances his own conflicting muses amidst the deliberate chaos.

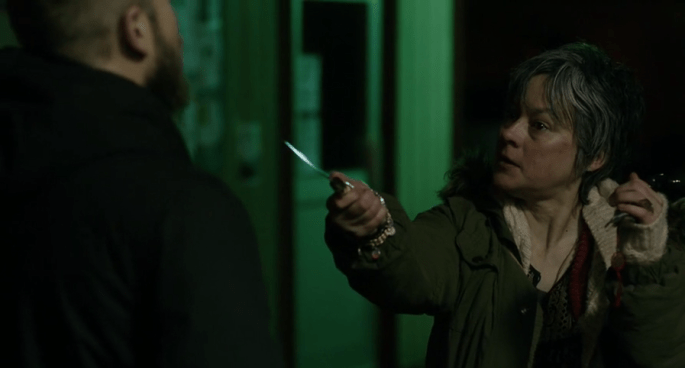

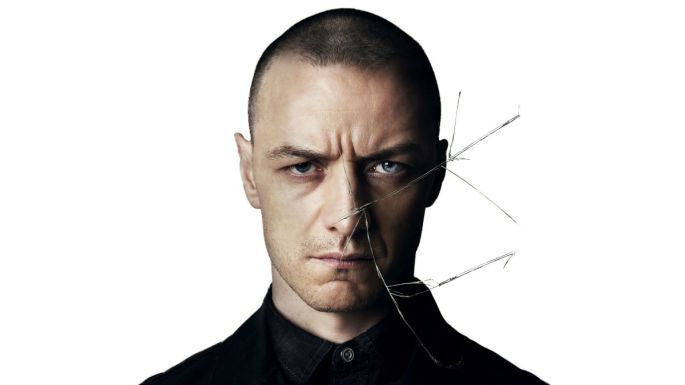

James McAvoy is absolutely intoxicating as Kevin Wendell Crumb, a man suffering from dissociative identity disorder who kidnaps a trio of teenage girls – Claire (Haley Lu Richardson), Marcia (Jessica Sula) and Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy) – after a particularly awkward birthday party and keeps them confined to a single locked cell underground for some undisclosed higher purpose, revealing more and more about his intentions through his various alter egos – including but not limited to a nine year old boy, an obsessive compulsive psychopath, and a woman with protective instincts not unlike a mother – which are constantly competing against one-another for dominance.

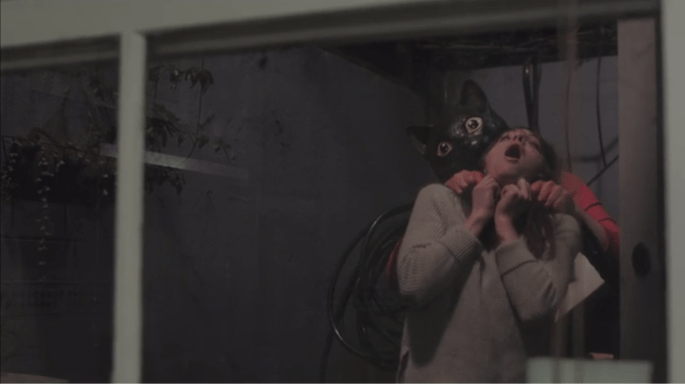

Due in no small part to the exquisite precision of “It Follows” cinematographer Mike Gioulakis, the walls, floors, closed and opened doors of Kevin’s seedy lair never breathe easy; in fact, they retain an intensely suffocating, sleazy ambience throughout that fits Shyamalan’s intentionally alienated (and perhaps alienating) direction like a glove. The director has always displayed a knack for manipulating the frame in unorthodox ways, and it serves him well for the purpose of immersive claustrophobia. Even the open air of the outside world feels tainted by palpable pulsating paranoia, as if escapism is utterly inexcusable in this disturbed domain.

A few of the more gleefully over-the-top indulgences in the film’s delightfully demented third act might prove to be slightly problematic, especially in regards to how seriously the connection between mental illness and childhood abuse is treated on a whole, but it makes for an unusually compelling spectacle. Only the final moments, which clumsily attempt to meld the preceding events with the enduring legacy of an earlier Shyamalan joint similarly about harnessing supernatural abilities, feel out of place in an otherwise exceptional example of exercising restraint and boundless, off-kilter ingenuity in equal measures.

As much as he goes for the jugular when he wants to get weird, it’s Shyamalan’s intuitive empathy that makes his best work utterly unforgettable. “Split” doesn’t claim to have all the answers to some of its bigger problems, and one suspects at times that its tongue may be planted firmly in its cheek, but it nevertheless stands as a satisfying exploration of inhuman actions and their potentially horrific repercussions; a mostly successful attempt to envision “monsters” inherent in our society as something more than that. It’s true that we’ve been here before, and so has M. Night, but what can you say? He’s damn good at what he does and it’s rather exhilarating to see him get in touch with the same unique gifts – as a storyteller, a preserver of perversion and perception alike – that he exhibited at a more tender age and elaborate on them in such a thoroughly satisfying way.

![elaine_wayne[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/elaine_wayne1.jpg?w=638&h=425)

![elaine_tearoom[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/elaine_tearoom1.jpg?w=638&h=425)

![manchester-by-the-sea-1[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/manchester-by-the-sea-11.jpg?w=685)

![489089306_640[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/489089306_6401.jpg?w=685)