“Ocean’s Eleven was my opportunity to make a movie that has no desire except to give you pleasure, where you surrender without embarrassment or regret.” – Steven Soderbergh

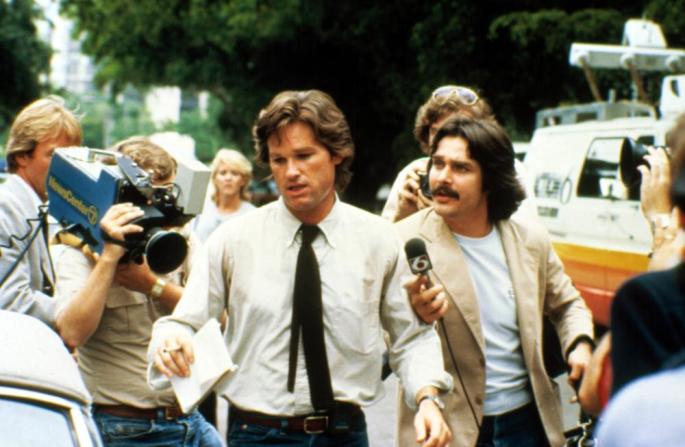

Fresh from the one-two success of Erin Brockovich (2000) and Traffic (2000), Steven Soderbergh made a conscious decision to shift gears and make a purely entertaining film for a major studio. He managed to convince movie stars George Clooney (whom he had already worked with on Out of Sight) and Brad Pitt to take major cuts in their multi-million dollar salaries and headline a remake of the Rat Pack heist film Ocean’s Eleven (1960). With Clooney and Pitt on board, Soderbergh was then able to get an impressive cast including the likes of Matt Damon and Julia Roberts (both of whom also agreed to take pay cuts) and avoid having his film come across as nothing more than a vanity project for a bunch of smug movie stars. On the contrary, Ocean’s Eleven (2001) is a slick heist film in the tradition of The Sting (1973) in the sense that you know the outcome (the good guys win) but the fun is in how they get there as Soderbergh utilizes every stylish technique that he has available at his disposal.

Daniel Ocean (Clooney) has just been released from prison and is eager to return to his high-end criminal enterprises. He sets his sights on Las Vegas with plans to rob three prestigious casinos: the MGM Grand, the Mirage, and the Bellagio, all of which keep their considerable sums of money in an ultra-secure hi-tech vault controlled by Terry Benedict (Andy Garcia) who, incidentally, is currently dating Danny’s ex-wife Tess (Roberts). It’s not going to be easy and so, with the help of his good friend and ace fixer Rusty Ryan (Pitt), they recruit nine experts to help them pull off a near-impossible heist. In addition to the heist, which serves as the main plot, Ted Griffin’s screenplay expertly weaves in a subplot involving Danny attempt to reconnect with Tess.

This film oozes cool right from the opening credits that play over a fantastic shot of the Atlantic City skyline at night accompanied by funky trip-hop type music by Northern Irish disc jockey David Holmes. We meet Rusty wasting his time teaching young movie stars (Holly Marie Combs and Topher Grace among others making fun of themselves) to play cards. We meet him in Hollywood with a cool groove playing over his establishing shot. This sequence is a bit of meta fun as we see Pitt, one of the biggest movie stars on the planet, teaching other movie stars playing a parody of themselves being totally clueless at playing poker only to eventually be hustled by a bemused Danny. Soderbergh even slides in a few sly inside jokes, like Danny asking Topher Grace if it’s hard to make the transition from television to film, which, of course, is exactly what Clooney did. Or, how Grace gets mobbed by autograph hounds while Clooney and Pitt are completely ignored.

One of the best sequences in the film is when Danny and Rusty recruit their crew. The scene where they convince Reuben Tishkoff (Elliott Gould) to bankroll their operation is a wonderful example of how expositional dialogue being delivered in the right way by the right actor can be entertaining and informative as Elliott Gould does a fantastic job of warning Danny and Rusty of just how dangerous Benedict is. From there, each character that Danny and Rusty approach is given their own introduction that briefly and succinctly highlights their unique skill and distinctive personality traits. Linus Caldwell (Damon) is an up-and-coming pickpocket with uncanny dexterity. There’s the Malloy brothers, Virgil (Casey Affleck) and Turk (Scott Caan), two drivers by trade with one of them having an affinity for remote controlled devices and a perchance for bickering and irritating each other, which provides a good source of humor. Livingston Dell (Eddie Jemison) is an electronics expert in the area of surveillance. Basher Tarr (Don Cheadle) is a demolitions expert with Don Cheadle sporting an obviously exaggerated Cockney accent. Yen (Shaobo Qin) is a diminutive top-of-the-line acrobat that can get in and out of any tight space. Finally, there is Saul Bloom (Carl Reiner), a retired flimflam man coaxed back into action by Rusty. Each actor is given at least one scene, often more, to come front and center and do their thing and this is done in a way that doesn’t distract you from the story at hand, which is quite an accomplishment with such a large cast.

David Holmes expertly mixes jazz, funk, soul and hip hop in a way that evokes groovy trip hop or acid jazz but in a retro way that evokes Quincy Jones circa the 1970s. The often-fat bass lines give certain musical cues a confident swagger. There is also plenty of Hammond organ and vibraphone looped to give a lounge-y kind of vibe at times. Later on in the film, Holmes brings in strings and brass to accentuate the romantic subplot between Danny and Tess. Holmes also incorporates songs, like Elvis Presley’s “A Little Less Conversation” to fantastic effect. This came out of watching the original Ocean’s Eleven as Holmes explained in an interview, “Then I tried to think of ways to identify with what was going on – with it being a contemporary film, how to be original, but set within the heart of Las Vegas. Which is where the Elvis song ‘A Little Less Conversation’ came about, because obviously Elvis had a really strong affiliation with Las Vegas, and that track has a very contemporary feel.”

Steven Soderbergh read Ted Griffin’s screenplay in an afternoon in January 2000. The next day he called producer Jerry Weintraub and told him he wanted to direct the film. What he liked about the script was that it didn’t evoke the original 1960 version but “had this one foot back in the heyday of the studio star-driven movie, like Howard Hawks or George Cukor.” Soderbergh had always been drawn to heist films because, “the conflicts are so clear and dramatic. This seemed to be everything that you want a big Hollywood film to be, on the script level.” He had just made two dramas – Erin Brockovich and Traffic – and wanted to make a fun movie. To prepare for shooting Ocean’s Eleven, he watched Ghostbusters (1984) because he was impressed at “that sort of physical scale [that] feels so tossed-off, with such understated performances and obvious generosity among all the performers.” He also studied films by David Fincher, Steven Spielberg and John McTiernan because they knew how to “orchestrate physical action the way I like to see it.” He looked at how these filmmakers used lens length and height, camera movement and editing, as well as, “how they used their extras, how they structured movements within shots that carried you to the next movement and the next.”

Soderbergh got George Clooney involved and half-jokingly told him, “let’s make it an Irwin Allen movie, where they used to have 10 stars.” Originally, the director considered casting Luke and Owen Wilson, Bruce Willis, and Ralph Fiennes as the villain. Once Clooney was on board, they got the rest of the cast to commit at radically reduced rates, starting with Brad Pitt. However, during filming, the cast stayed in their own 7,000-square-foot villas at the Bellagio. Before shooting, Soderbergh told his cast, “Show up ready to work. If you think you’re just going to walk through this, you’re mistaken. If anybody gets smug, we’re dead.” Soderbergh wanted to shoot in the Bellagio, the MGM Grand and the Mirage – an impossible feat for more mere mortals; however, Weintraub had the connections and the clout to make it happen. The production was allowed to shoot on the floor of the casinos during the day, which nobody is given access to and the casino bosses even shut down entire pits for Soderbergh to shoot in. This allowed the director to design shots that were complicated and large in scale.

Soderbergh wanted the lighting for Ocean’s Eleven to be based in reality and to look like it wasn’t lit at all – not a problem in Las Vegas, a place overloaded with every kind of light imaginable. At times, Soderbergh would add some color to enhance the mood for dramatic purposes in order to put the audience inside the world of the film. He also realized that the locations played a large part in the plot and was interested in showing as much of the environment as possible. One challenge Soderbergh faced was the logistics of filming big dialogue scenes with Danny and his crew in a visually interested way. He had a lot of people in confined spaces and didn’t want these scenes to be boring. So, he attempted to frame shots that clearly established where everyone was while also giving them enough depth and geometry to make the characters interesting to look at.

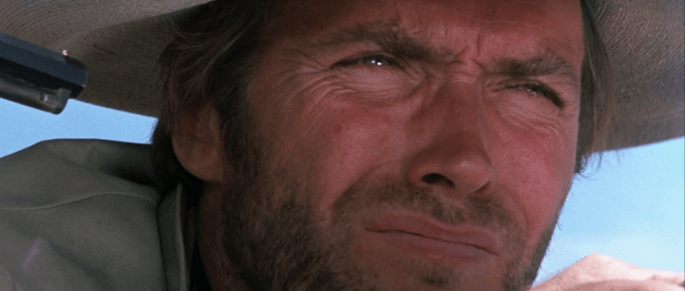

In a nice touch, Ocean’s Eleven never waxes nostalgic about the original film but instead is wistful about Las Vegas as it was in the 1960s when the casinos were still run by the Mob and had yet to be corporatized and Disney-fied. This is reinforced in one of the motivations Danny has of robbing Benedict. It’s not just that he’s dating his ex-wife but Benedict also recently demolished one of the last old school casinos left in Vegas. Unlike Benedict, Danny respects the past and recruits Reuben and Saul, veteran con artists whose heyday was the ‘60s. It’s great to see Soderbergh giving actors like Gould and Reiner screen-time in a major studio film. These guys don’t work nearly enough and their performances in Ocean’s Eleven are a potent reminder of how good they can be if given the right material and the opportunity. Entrusted with only his second major studio film with an A-list budget, Soderbergh effortlessly orchestrates a fun, engaging popcorn movie like an old pro that has been doing this for their entire career.