With the massive commercial success of Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), other Hollywood studios scrambled to find their own comic book franchise in the hopes of replicating the boffo box office of the Caped Crusader. With the notable exception of Dick Tracy (1990), most of these films failed to appeal to a mainstream audience. These included pulp serial heroes The Shadow (1994) and The Phantom (1996), and the independent comic book The Rocketeer. Originally created by the late Dave Stevens, it paid homage to the classic pulp serials of the 1930s. For some reason, Disney decided that it would be their tent-pole summer blockbuster for 1991, cast two unproven leads – Billy Campbell and Jennifer Connelly – and hired Steven Spielberg protégé, Joe Johnston to direct. Despite promoting the hell out of it and spending a ton of money on merchandising, The Rocketeer (1991) underperformed at the box office.

It’s a shame because out of the lot of retro comic book films done in the 1990s, The Rocketeer was the best one and the most faithful to its source material. While both The Shadow and The Phantom looked great, they were flawed either in casting or with their screenplays while Dick Tracy was top-heavy with villains and director (and star) Warren Beatty’s ego, but The Rocketeer had the advantage of its creator actually being involved in bringing his vision to the big screen. The end result was a fun, engaging B-movie straight out Classic Hollywood Cinema albeit with A-list production values. The film has quietly cultivated a cult following and deserves to be rediscovered.

Cliff Secord (Billy Campbell) is a young, hotshot pilot who races planes for a living with the help of his trusted mechanic and good friend Peevy (Alan Arkin). One day, while out testing his new plane, Cliff stumbles across an experimental jetpack stolen from Howard Hughes (Terry O’Quinn). Soon, he finds himself mixed up with the FBI, who want to recover it, and unscrupulous gangsters who stole it in the first place. Also thrown into the mix is Neville Sinclair (Timothy Dalton), an Errol Flynn-type matinee idol who wants the jetpack for his own nefarious agenda. Cliff’s beautiful girlfriend Jenny Blake (Jennifer Connelly) is an aspiring actress who catches Sinclair’s eye, which further complicates Cliff’s life. With Peevy’s help, Cliff figures out how to use the jetpack and fashions himself an alter ego by the name of the Rocketeer.

Billy Campbell does a fine job as the scrappy Cliff Secord. He certainly looks the part and has great chemistry with co-star Jennifer Connelly (they fell in love while making the film). Connelly plays Jenny as the gorgeous girl-next-door and looks like she stepped out of a 1930s film. Jenny loves Cliff but dreams of being a movie star, not hanging around the airfield. Connelly, with her curvy figure, shows off her outfits well and does the best with what is ostensibly a damsel in distress role.

Timothy Dalton has a lot of fun playing the dashing cad as evident in the scene where he “accidentally” wounds a fellow actor during filming for stealing a scene from him. Sinclair is a vain movie star with big plans and there’s a glimmer in Dalton’s eye as he relishes playing the dastardly baddie. Alan Arkin is also good in the role of Peevy – part absent-minded professor-type and part father figure to Cliff.

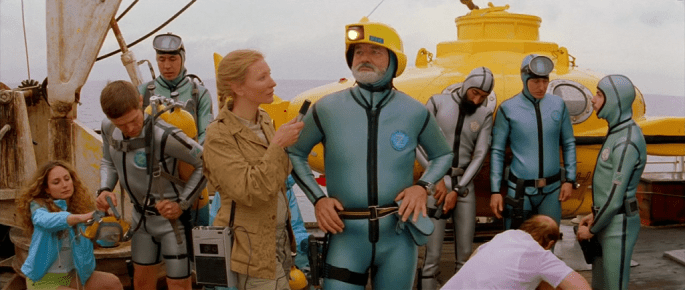

The Rocketeer features a solid supporting cast with the likes of Ed Lauter playing a no-nonsense FBI agent, Terry O’Quinn as the brilliant Howard Hughes, Jon Polito as the money-grubbing airfield owner, and Paul Sorvino as a blustery gangster begrudgingly in league with Sinclair. His casting is a nice nod to the patriarchal mobster he played in GoodFellas (1990) only a lot less menacing (this is Disney after all). The always entertaining O’Quinn is particularly fun to watch as a dashing Hughes that could have easily stepped out of Francis Ford Coppola’s love letter to American ingenuity, Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988).

The attention to period detail, in particular the vintage planes, is one The Rocketeer’s strengths. The film gets it right with the clothes that people wear and how they speak so that you feel transported back to this era. The recreation of old school opulence is fantastic as evident in the South Seas nightclub sequence where Sinclair works his charms on Jenny. Even Joe Johnston’s direction feels like a throwback to classic Hollywood filmmaking as he gives the flying sequences the proper visual flair that they deserve. He wisely keeps things simple, never trying to get too fancy or show-offy as he takes a page out of his mentor, Steven Spielberg’s book. There’s never any confusion as to what is happening or where everyone is – something that seems to be missing from a lot of action films thanks to the popularity of the Bourne films. Johnston is an interesting journeyman director whose best work is old school action/adventure films, like Hidalgo (2004), or slice-of-life Americana, like October Sky (1999), which is why he was the wrong choice to helm the ill-fated reboot of The Wolfman (2010) and the right director for Captain America: The First Avenger (2011).

Filmmaker Steve Miner (Friday the 13th, Parts II and III) was the first person to option the film rights to Dave Stevens’ independent comic book The Rocketeer but he ended up straying too far from the original concept and his version died an early death. Screenwriters Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo (Trancers and Zone Troopers) were given the option in 1985. Stevens liked them because “their ideas for The Rocketeer were heartfelt and affectionate tributes to the 1930’s with all the right dialogue and atmosphere. Most people would approach my characters contemporarily, but Danny and Paul saw them as pre-war mugs.” Their subsequent screenplay kept the comic book’s basic plot intact but fleshed it out to include the Hollywood setting and the climactic battle against a Nazi zeppelin. They also tweaked Cliff’s girlfriend to avoid comparisons (and legal hassles) to Bettie Page (Stevens’ original inspiration), changing her from a nude pin-up model to a Hollywood extra while also changing her name from Betty to Jenny.

Filmmaker Steve Miner (Friday the 13th, Parts II and III) was the first person to option the film rights to Dave Stevens’ independent comic book The Rocketeer but he ended up straying too far from the original concept and his version died an early death. Screenwriters Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo (Trancers and Zone Troopers) were given the option in 1985. Stevens liked them because “their ideas for The Rocketeer were heartfelt and affectionate tributes to the 1930’s with all the right dialogue and atmosphere. Most people would approach my characters contemporarily, but Danny and Paul saw them as pre-war mugs.” Their subsequent screenplay kept the comic book’s basic plot intact but fleshed it out to include the Hollywood setting and the climactic battle against a Nazi zeppelin. They also tweaked Cliff’s girlfriend to avoid comparisons (and legal hassles) to Bettie Page (Stevens’ original inspiration), changing her from a nude pin-up model to a Hollywood extra while also changing her name from Betty to Jenny.

Bilson and DeMeo submitted their seven-page outline to Disney in 1986. They studio put the script through an endless series of revisions and, at one point, frustrated by the seemingly endless process, the two screenwriters talked to Stevens about doing The Rocketeer as a smaller film shot in black and white. The involvement of Disney put the project on a much bigger level as the writers remembered, “you can imagine the commitment Disney was making to develop a series of movies around a character. They even called it their Raiders of the Lost Ark.” With Stevens’ input, Bilson and DeMeo developed their script with director William Dear (Harry and the Hendersons) who changed the zeppelin at the film’s climax to a submarine. Over five years, the mercurial studio fired and rehired Bilson and DeMeo three times. DeMeo said, “Disney felt that they needed a different approach to the script, which meant bringing in someone else. But those scripts were thrown out, and we were always brought back on.”

They found this way of working very frustrating as the studio would like “excised dialogue three months later. Scenes that had been thrown out two years ago were put back in. what was the point?” Disney’s biggest problem with the script was all of the period slang peppered throughout. Executives were worried that audiences wouldn’t understand what the characters were saying. One of their more significant revisions over this time period was to make Cliff and Jenny’s “attraction more believable … how do we bring Jenny into the story and revolve it around her, and not just create someone who’s kidnapped and has to be saved?” DeMeo said. In 1990, their third major rewrite finally got the greenlight from Disney. However, when the studio acquired the rights to the Dick Tracy film from Universal Studios, DeMeo was worried that executives would dump The Rocketeer in favor of the much more high-profile project. However, when Dick Tracy failed to perform as well at the box office as Disney had hoped, DeMeo’s fears subsided.

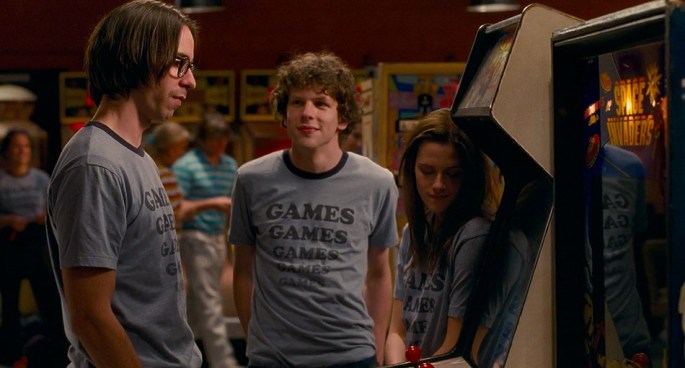

All kinds of actors were considered for the role of Cliff Secord, including Bill Paxton, who almost got it, and Vincent D’Onofrio, who was offered the role but turned it down. Finally, Billy Campbell was cast as Cliff. Prior to this film, his biggest role to date was regular on the Michael Mann-produced television show, Crime Story. For the role of Jenny, Sherilyn Fenn, Kelly Preston, Diane Lane, and Elizabeth McGovern were all considered but lost out to Jennifer Connelly, fresh from making the comedy, Career Opportunities (1991). Dave Stevens wanted Lloyd Bridges to play Peevy but he turned the film down and Alan Arkin was cast instead. The Neville Sinclair role was offered to Jeremy Irons and Charles Dance before Timothy Dalton accepted the role.

Campbell wasn’t familiar with Stevens’ comic book when he got the part but quickly read it and books on aviation while also listening to period music. The actor also had a fear of flying but overcame it with the help of the film’s aerial coordinator Craig Hosking. To ensure Campbell’s safety, he was doubled for almost all of the Rocketeer’s flying sequences. Hosking said, “What makes The Rocketeer so unique was having several one-of-a-kind planes that hadn’t flown in years,” and this included a 1916 standard bi-wing, round-nosed, small-winged Gee Bee plane.

The numerous delays forced William Dear to leave the production and director Joe Johnston signed on to direct. He was a fan of the comic book and when he inquired about its film rights was told that Disney already had it in development. He approached the studio and was quickly hired to take over when Dear departed. Johnston said, “One of the great appeals of Stevens’ work was his attention to detail, which really placed the reader in the period. I’ve tried to do the same thing cinematically.” Pre-production on the film started in early 1990 with producer Larry Franco in charge of securing locations for the film. He found an abandoned World War II landing strip in Santa Maria, which the filmmakers used to build the mythical Chaplin Air Field. The Rocketeer’s attack on the Nazi zeppelin was filmed near the Magic Mountain amusement park in Indian Dunes. The film was shot over 96 days and ended up going over schedule due to weather and mechanical problems.

Like The Right Stuff (1983) before it, The Rocketeer is a love letter to the wonders of aviation and the brave souls that risked their lives pushing the envelope. In a nice touch, Cliff even chews Beeman’s gum, the same kind that Chuck Yeager uses in The Right Stuff. The comic book is masterfully translated to the big screen, right down to recreating the iconic Bull Dog Diner. The filmmakers also got all the details of Cliff and his alter ego right, including the casting of Billy Campbell. The same goes for Jenny, although, because Disney backed the film, they downplayed the blatant homage her character was to famous pin-up model Bettie Page. With Dave Stevens untimely passing in 2008, watching this film is now a bittersweet experience but there is some comfort in that at least he got to see his prized creation brought vividly to life even if failed to catch on with the mainstream movie-going public. The Rocketeer is flat-out wholesome fun with nothing more on its mind than to tell an entertaining story and take us on an exciting adventure.

Like The Right Stuff (1983) before it, The Rocketeer is a love letter to the wonders of aviation and the brave souls that risked their lives pushing the envelope. In a nice touch, Cliff even chews Beeman’s gum, the same kind that Chuck Yeager uses in The Right Stuff. The comic book is masterfully translated to the big screen, right down to recreating the iconic Bull Dog Diner. The filmmakers also got all the details of Cliff and his alter ego right, including the casting of Billy Campbell. The same goes for Jenny, although, because Disney backed the film, they downplayed the blatant homage her character was to famous pin-up model Bettie Page. With Dave Stevens untimely passing in 2008, watching this film is now a bittersweet experience but there is some comfort in that at least he got to see his prized creation brought vividly to life even if failed to catch on with the mainstream movie-going public. The Rocketeer is flat-out wholesome fun with nothing more on its mind than to tell an entertaining story and take us on an exciting adventure.

Reynolds is a native Texan and Fandango is a love letter, of sorts, to the state. At one point, Phil criticizes Texas and Gardner replies almost reverentially, “It’s wild, Philip. Always has been. Always will be.” As if to reinforce this point, Waggener laments calling off his wedding after coming across a plaque recognizing the McLean Massacre, a place where two Indian fighters were ambushed and killed in 1837. The film has all the energy and vitality of a first-time director who’s willing to go for it and has a burning desire to tell a story. However, the film’s joyful celebration of youth is tempered by a melancholic tone that surfaces periodically as the Groovers realize that their carefree college days are over and the sobering reality of army boot camp and Vietnam hangs over their heads like a dark storm cloud. As Reynolds said in a recent interview, Fandango is “the end of era for these four, and some realized it more than others.” He would graduate to bigger, more ambitious studio films like Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Waterworld (1995), but none of his subsequent work has had the personal touch of Fandango. It’s as if Reynolds lost track of where he came from and had his personality, which is apparent in every frame of his debut feature, removed by the impersonal machinations of Hollywood.

Reynolds is a native Texan and Fandango is a love letter, of sorts, to the state. At one point, Phil criticizes Texas and Gardner replies almost reverentially, “It’s wild, Philip. Always has been. Always will be.” As if to reinforce this point, Waggener laments calling off his wedding after coming across a plaque recognizing the McLean Massacre, a place where two Indian fighters were ambushed and killed in 1837. The film has all the energy and vitality of a first-time director who’s willing to go for it and has a burning desire to tell a story. However, the film’s joyful celebration of youth is tempered by a melancholic tone that surfaces periodically as the Groovers realize that their carefree college days are over and the sobering reality of army boot camp and Vietnam hangs over their heads like a dark storm cloud. As Reynolds said in a recent interview, Fandango is “the end of era for these four, and some realized it more than others.” He would graduate to bigger, more ambitious studio films like Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Waterworld (1995), but none of his subsequent work has had the personal touch of Fandango. It’s as if Reynolds lost track of where he came from and had his personality, which is apparent in every frame of his debut feature, removed by the impersonal machinations of Hollywood.

This film does not quite look like it was shot in the ‘70s but made by someone who grew up in that decade. Rejects was made by a horror film fan for horror film fans. Zombie has created a truly disturbing horror movie with no real redeemable characters, that is refreshingly unpredictable and this is what makes it so scary, like the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Both movies are feverish nightmares except that in Massacre you felt sympathy for the female protagonist. The Devil’s Rejects does not even have that. You may find yourself rooting for the Firefly family early on but Zombie quickly rejects this notion by portraying them as truly irredeemable people. There is no sappy love story or cop-out ending and this remains true to many of the nihilistic movies of the ‘70s. Horror film obsessives always brace themselves for the wimp out ending — it is the downfall of so many horror films — Rejects does not make this mistake. Zombie has shown a real growth as a filmmaker, creating I daresay a modern horror masterpiece.

This film does not quite look like it was shot in the ‘70s but made by someone who grew up in that decade. Rejects was made by a horror film fan for horror film fans. Zombie has created a truly disturbing horror movie with no real redeemable characters, that is refreshingly unpredictable and this is what makes it so scary, like the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Both movies are feverish nightmares except that in Massacre you felt sympathy for the female protagonist. The Devil’s Rejects does not even have that. You may find yourself rooting for the Firefly family early on but Zombie quickly rejects this notion by portraying them as truly irredeemable people. There is no sappy love story or cop-out ending and this remains true to many of the nihilistic movies of the ‘70s. Horror film obsessives always brace themselves for the wimp out ending — it is the downfall of so many horror films — Rejects does not make this mistake. Zombie has shown a real growth as a filmmaker, creating I daresay a modern horror masterpiece.

Filmmaker Steve Miner (Friday the 13th, Parts II and III) was the first person to option the film rights to Dave Stevens’ independent comic book The Rocketeer but he ended up straying too far from the original concept and his version died an early death. Screenwriters Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo (Trancers and Zone Troopers) were given the option in 1985. Stevens liked them because “their ideas for The Rocketeer were heartfelt and affectionate tributes to the 1930’s with all the right dialogue and atmosphere. Most people would approach my characters contemporarily, but Danny and Paul saw them as pre-war mugs.” Their subsequent screenplay kept the comic book’s basic plot intact but fleshed it out to include the Hollywood setting and the climactic battle against a Nazi zeppelin. They also tweaked Cliff’s girlfriend to avoid comparisons (and legal hassles) to Bettie Page (Stevens’ original inspiration), changing her from a nude pin-up model to a Hollywood extra while also changing her name from Betty to Jenny.

Filmmaker Steve Miner (Friday the 13th, Parts II and III) was the first person to option the film rights to Dave Stevens’ independent comic book The Rocketeer but he ended up straying too far from the original concept and his version died an early death. Screenwriters Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo (Trancers and Zone Troopers) were given the option in 1985. Stevens liked them because “their ideas for The Rocketeer were heartfelt and affectionate tributes to the 1930’s with all the right dialogue and atmosphere. Most people would approach my characters contemporarily, but Danny and Paul saw them as pre-war mugs.” Their subsequent screenplay kept the comic book’s basic plot intact but fleshed it out to include the Hollywood setting and the climactic battle against a Nazi zeppelin. They also tweaked Cliff’s girlfriend to avoid comparisons (and legal hassles) to Bettie Page (Stevens’ original inspiration), changing her from a nude pin-up model to a Hollywood extra while also changing her name from Betty to Jenny. Like The Right Stuff (1983) before it, The Rocketeer is a love letter to the wonders of aviation and the brave souls that risked their lives pushing the envelope. In a nice touch, Cliff even chews Beeman’s gum, the same kind that Chuck Yeager uses in The Right Stuff. The comic book is masterfully translated to the big screen, right down to recreating the iconic Bull Dog Diner. The filmmakers also got all the details of Cliff and his alter ego right, including the casting of Billy Campbell. The same goes for Jenny, although, because Disney backed the film, they downplayed the blatant homage her character was to famous pin-up model Bettie Page. With Dave Stevens untimely passing in 2008, watching this film is now a bittersweet experience but there is some comfort in that at least he got to see his prized creation brought vividly to life even if failed to catch on with the mainstream movie-going public. The Rocketeer is flat-out wholesome fun with nothing more on its mind than to tell an entertaining story and take us on an exciting adventure.

Like The Right Stuff (1983) before it, The Rocketeer is a love letter to the wonders of aviation and the brave souls that risked their lives pushing the envelope. In a nice touch, Cliff even chews Beeman’s gum, the same kind that Chuck Yeager uses in The Right Stuff. The comic book is masterfully translated to the big screen, right down to recreating the iconic Bull Dog Diner. The filmmakers also got all the details of Cliff and his alter ego right, including the casting of Billy Campbell. The same goes for Jenny, although, because Disney backed the film, they downplayed the blatant homage her character was to famous pin-up model Bettie Page. With Dave Stevens untimely passing in 2008, watching this film is now a bittersweet experience but there is some comfort in that at least he got to see his prized creation brought vividly to life even if failed to catch on with the mainstream movie-going public. The Rocketeer is flat-out wholesome fun with nothing more on its mind than to tell an entertaining story and take us on an exciting adventure.

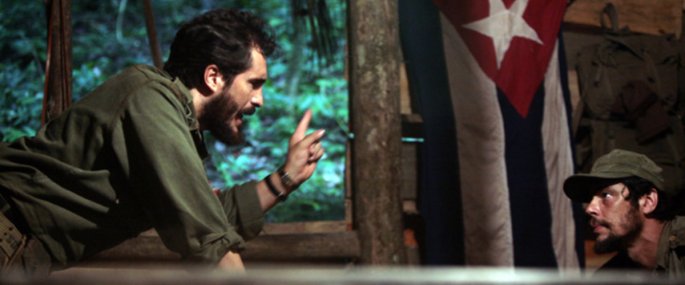

Che is ultimately a study in contrasts. What worked in Cuba did not work in Bolivia. Soderbergh’s film illustrates the differences. In Cuba, the revolutionaries were able to get the trust and support of the peasants while in Bolivia they feared the rebels. It must also be said that Castro played a key role in the success of the Cuban revolution and his absence in Bolivia, the galvanizing effect he had, is sorely missed. With Che, Soderbergh has created an unusual biopic that does its best to not try and manipulate you into feeling one way or another about the revolutionary. Instead, it shows two very different examples of the man’s philosophies put into practice and how they played out – one a success and the other a failure. Che was a polarizing historical figure long before this film came along and will continue to be long afterwards.

Che is ultimately a study in contrasts. What worked in Cuba did not work in Bolivia. Soderbergh’s film illustrates the differences. In Cuba, the revolutionaries were able to get the trust and support of the peasants while in Bolivia they feared the rebels. It must also be said that Castro played a key role in the success of the Cuban revolution and his absence in Bolivia, the galvanizing effect he had, is sorely missed. With Che, Soderbergh has created an unusual biopic that does its best to not try and manipulate you into feeling one way or another about the revolutionary. Instead, it shows two very different examples of the man’s philosophies put into practice and how they played out – one a success and the other a failure. Che was a polarizing historical figure long before this film came along and will continue to be long afterwards.

Easy Rider’s nihilistic ending would go on to inspire similar-minded road movies in the ‘70s, like Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Vanishing Point (1971), and Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973). Easy Rider’s legacy is impressive. It paved the way for the Movie Brats (Coppola, Lucas, Scorsese, et al) in the ‘70s, which was the golden age of American filmmaking where the director was king.

Easy Rider’s nihilistic ending would go on to inspire similar-minded road movies in the ‘70s, like Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Vanishing Point (1971), and Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1973). Easy Rider’s legacy is impressive. It paved the way for the Movie Brats (Coppola, Lucas, Scorsese, et al) in the ‘70s, which was the golden age of American filmmaking where the director was king.