Ever since Ali was released in 2001, I have felt that it has been one of Michael Mann’s most under-appreciated films. It received decidedly mixed reviews and underperformed at the box office. While Will Smith was praised for his impressive physical transformation into legendary boxer Muhammed Ali, the film itself was criticized for revealing nothing new about the man. Herein lies the problem that Mann faced: how do you shed new light on one of the most documented historical figures of the 20th century? His angle on the material was to look inwards.

Proposals for an Ali biopic had been around since the early 1990s when producer and one-time business partner of the boxer, Paul Ardaji, pitched the idea to the man on his 50th birthday. Ali gave the project his blessing and financing quickly fell into place. A number of scripts were written by the likes of Gregory Allen Howard (Remember the Titans) and Stephen J. Rivele and Christopher Wilkinson (Nixon), but they all failed to please the powers that be. The project bounced around various studios for years as executives tried to decide who should make it, who should star in it, and would it even make a profit? In 1991, Oliver Stone met with Ali about making a film about his life but the collaboration ended when the director refused to share creative control. In 1992, Ali’s best friend and personal photographer Howard Bingham and Ali’s wife Lonnie got together with Ardaji. Gregory Allen Howard’s take on Ali was delivered in 1996. His angle was that the key to the boxer’s life was his relationship with his father, who ignored him.

When Will Smith met Ali in 1997, the boxer asked the actor to play him in the film. Smith was flattered but said no. He was not ready and too intimidated for such a demanding role. The actor almost did it when Barry Sonnenfeld agreed to direct. Both men had worked together on the Men in Black movies and Wild Wild West (1999). Thankfully, their version never saw the light of day. After he turned 30, Smith realized that he had to make the decision about playing Ali. However, when no one could settle on a script, Sonnenfeld dropped out. There were several more rewrites and directors, including Curtis Hanson who expressed interest. Smith was ready to give up on the project.

It then came down to Spike Lee or Michael Mann to fill the director’s chair left empty by Sonnenfeld. Sony Pictures, the studio bankrolling the film, was faced with a $100+ million budget and went with Mann who had just received several Academy Award nominations and all kinds of critical praise for The Insider (1999). Upset, Lee voiced his anger through a friend in The New York Post: “Only a black man could do justice to the Cassius Clay story,” he was reported as saying. Mann responded that he “wanted the film to come from the point of view of the main character, Muhammed Ali. I’m not interested in showing a white man’s idea of how someone suffered racism. The perspective of the film has to be African-American.” When asked why he did not pick a black director Ali said that he wanted the best qualified person regardless of color, and his wife said, “Muhammad didn’t want it to be a movie just for black audiences. He wanted it to be a movie for all cultures and all people.”

When Mann was approached to direct he wasn’t even sure if he wanted to tackle such challenging subject matter but was sure of one thing; he did not want to make a docudrama or idealize Ali’s life. After meeting with Ali and his wife, they told him that they did not want “a teary Hallmark-greeting version of Muhammad Ali … What they didn’t want I didn’t want,” Mann remembers. The director liked Rivele and Wilkinson’s screenplay but rejected their flashback structure and their use of Ali’s 1978 fight, the “Thrilla in Manila,” as the present frame of the story. Mann felt that Ali’s 1974 fight in Zaire was more significant. He was also not interested in spelling things out for the audience: “I wanted to insert you into the stream of this man’s life, orient you without doing it in a blatant way with exposition.” Ironically, this is what would scare off a lot of people.

Smith’s agent arranged a meeting with Mann that changed his attitude towards the film. According to the actor, it was “the clear picture he had of the road from Will Smith to Muhammed Ali. He explained it in a way that made it seem, in my mind at least, not so utterly impossible, just marginally improbable.” Smith and Mann agreed that the film’s focus should be on ten turbulent years of Ali’s life, from 1964 to 1974. The director set the film during these years because “that formation of everything by ’74 is the beginning of what is now culturally in the United States.” Mann identified Ali with the spirit of change that occurred in the 1960s. “He consistently defied the establishment and its conventions, and we loved him for it.” Ali led such a colorful, eventful life that a focused story was crucial to the film. Mann said in an interview, “It would be catastrophic to divert into every interesting story. Everything this guy does is fascinating. I could have made an entire movie about Ali’s relation to women. Music, Cadillac convertibles and women. It would have been great.”

By February 23, 2000, Mann signed on to the film and went to work transforming Will Smith into Ali. Smith remembers that Mann created the “Muhammad Ali Course Syllabus” that began with a study of the boxer’s physical attributes: “learning to run how he ran, to eat the food he ate, spar the way he sparred. Essentially creating the physical life and physical appearance of Muhammad Ali.” From there, Smith moved on to the mental and emotional aspects and finally the man’s spirituality. Boxer trainer-choreographer Darrell Foster spent a year training Smith. Foster was Sugar Ray Leonard’s conditioning coach when the boxer turned pro. According to Foster, the key to becoming Ali was “looking for specific movements. Hand speed, ring generalship, how he made guys miss. Will had to become Ali, because you can’t demonstrate those moves through choreography.” Foster created a high-carb, high-protein diet for Smith and had him run in combat boots through snow in the thin air of Aspen, Colorado for ten months before the start of filming. His training schedule consisted of five miles of roadwork starting at 5:30 am, in the gym at 11:30 am, six days a week for three hours of ring work and weight training, watching fight films at 3 pm, and weight training in the evening. Smith put on 35 pounds of pure muscle in four months and went from bench-pressing 175 pounds to being able to press a very impressive 365 pounds. The finishing touch was being fitted with a hairpiece and a prosthetic nose.

For the fights, Foster started Smith on the basics: balance, footwork and defense. Then, he worked with the actor on the offensive aspects: a mix of overhand rights, hooks and upper cuts. Foster remembers that Smith “thought he knew how to fight because he had some street fights. But really, he couldn’t fight at all.” Smith worked on his hand and eye reflexes in order to perform eleven of Ali’s signature moves. Smith spent days studying film of Ali, including early footage shot when he was an Olympic boxing champion to interviews with Howard Cosell. Much of the material, unseen for years, was supplied by Leon Gast, a documentary filmmaker who made When We Were Kings (1996), a celebrated and acclaimed documentary about Ali’s championship bout with George Foreman. Smith also took classes in Islamic studies at the University of California.

The focus on the years 1964 to 1974 are arguably the most fascinating ones of Ali’s life because they are so rife with dramatic possibilities. It was during this period that Ali became the World Boxing Champion after beating Sonny Liston, then lost it when he refused to serve as a foot soldier in the Vietnam War, and finally reclaimed the Championship Title after beating the odds-on favorite, George Foreman in Zaire. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval in the United States with the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Finally, Ali also shows the man’s private side: his numerous wives and failed marriages, and his friendships with Malcolm X and Howard Cosell.

The focus on the years 1964 to 1974 are arguably the most fascinating ones of Ali’s life because they are so rife with dramatic possibilities. It was during this period that Ali became the World Boxing Champion after beating Sonny Liston, then lost it when he refused to serve as a foot soldier in the Vietnam War, and finally reclaimed the Championship Title after beating the odds-on favorite, George Foreman in Zaire. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval in the United States with the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Finally, Ali also shows the man’s private side: his numerous wives and failed marriages, and his friendships with Malcolm X and Howard Cosell.

Mann immediately immerses the audience in the time period with a montage of footage that features Sam Cooke performing in front of a live audience juxtaposed with Ali jogging alone at night and being harassed briefly by the police. Mann then goes into a montage of Ali training and two boxers fighting with Ali watching. Mann fractures time by also intercutting footage of Ali as a child witnessing the brutality of racism and its effects as he sees a newspaper article about the vicious beating of Emmet Till. The film then cuts back to a mature Ali sitting in on a lecture by Malcolm X. The entire montage is masterfully edited to the beats of a medley of Sam Cooke songs. This opening sequence establishes the Impressionistic take that Mann is to going to have on Ali’s life. It is also one of his most complex, layered opening credits sequence because he shifts time frames and presents us with all of these apparently unconnected images without explaining them. This is done on purpose in order to establish a mood, give an impression of the look and feel of the film and to set up that we are seeing the world through Ali’s eyes.

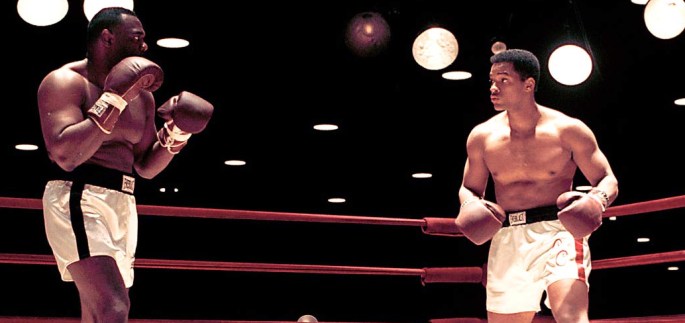

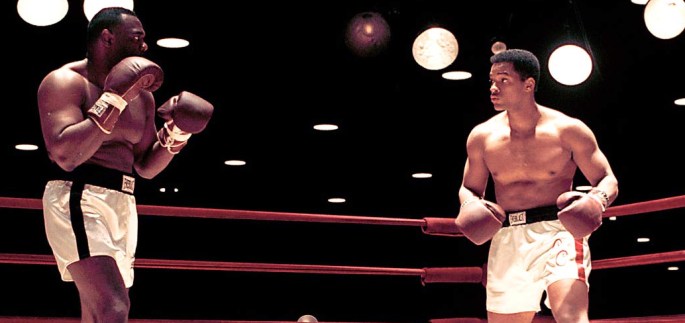

The fight scenes are covered from every conceivable angle as Mann cuts back and forth from shots outside and inside the ring. The first shot we get of the ring is a close-up of the red ropes and in Mann’s films this color signifies danger. There is the potential for Ali to not just lose the fight but possibly his life. This is a risk every time a boxer steps into the ring. In the Liston fight, Mann alternates between camerawork inside the ring, with tight and close point-of-view angles so that we are right in the ring with the boxers, and shots just outside of the ring but still close to the fighters. This gives the fight scenes a real visceral impact and immediacy that has not been seen since Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980). The Liston fight also shows how Ali could work a crowd of boxing fans just as well and in just the same way as the crowd of journalists before the fight.

Unlike most boxing films, Mann wanted to get inside the ring in order “to bring you inside the strategy and tactics, to bring you into the round as far as I could.” To this end, Mann would often be in the ring with the fighters with a very small digital camera. To achieve the most realistic fight scenes possible, Mann really had Smith and the other boxers hit each other. The director recalled one such incident: “When James Toney as Joe Frazier knocks Will down, we did three takes of that — every single one of those left hooks he connected. When Will stands up on the one that’s in the film, that wobble is not acting — you can tell how shaky he is.”

Mann also uses a cool, blue color to suggest intimacy and does so in the scene where Ali and Sonji (Jada Pinkett Smith), who would become his first wife, dance in a nightclub. They are close together, flirting with each other as Mann drenches the scene in blue much like he did with Neil McCauley entering his house in Heat (1995) and Will and Molly making love in Manhunter (1986). Ali is temporarily in an area of safety and love but this will change very soon.

After an interview with legendary broadcaster Howard Cosell (Jon Voight), Ali’s life takes a turn for the worse as he refuses to be inducted in the Army and is arrested. He then denounces the war in an interview and is subsequently labeled as being unpatriotic. He is stripped of his boxing title as Heavyweight Champion of the World, his boxing license and his passport. Like Jeffrey Wigand in The Insider, Ali is threatened by the powers that be for telling the truth and being his own man. It becomes obvious that this is a war of attrition in an effort to bleed Ali dry financially and threaten him with five years in jail. Then, as if to add insult to injury, the Temple of Islam suspends him just like they did to Malcolm X.

Cosell and Ali meet up and the veteran broadcaster, conscious of how bad off his friend is but not acknowledging it publicly, puts him on television despite network pressure. Cosell allows Ali to speak his piece about his ban and dazzles everyone again with his showmanship. It really is a testimony to Cosell that he did this. When everyone else had abandoned Ali, the T.V. personality stuck by him and used his considerable clout to put him back in the public eye. This interview is the turning point for Ali who wins a fight. Only then does Herbert and the Temple of Islam come back to him but Ali makes it clear that they do not own him. His eyes have been opened and he now knows just how much he can trust them.

Ali culminates with the legendary Rumble in the Jungle where Ali fought George Foreman in Zaire. Ali was not the favorite going in as Foreman was younger, stronger and the Champ. Mann, again, hints at the potential danger of this opponent when we see Foreman training, pounding a punching bag with powerful hits all with a greenish filter, a sign of peril in a Mann film. Sure enough, during this period Ali drives away his second wife (Nona Gaye) who does not like his relationship with the Temple of Islam because she feels that they are exploiting him. While still married to her, Ali becomes interested in a female journalist (Michael Michele) from Los Angeles who is in Zaire doing a profile on the boxer. This relationship effectively ruins his second marriage and Mann does not gloss over this showing that Ali was clearly in the wrong.

This portion of the film was shot in Johannesburg, South Africa and from there, an hour journey to Maputo, Mozambique because Mann liked the architecture in Maputo. In 1974, the legendary “Rumble in the Jungle” bout between Ali and George Foreman took place in Kinshasa, Zaire which had since become the Democratic Republic of Congo, but there was too much political unrest for Mann to shoot there in 2000. Associate producer Gusmano Gesaretti remembers that Mann fell in love with the architecture in Maputo. It was predominantly built by the Portuguese during the middle to later part of the century with buildings done in Art Deco-style curves and arches alongside others with straight lines in the block style of the 1960s. All were very aged and weather-beaten and looked very much the way Kinshasa was in the 1970s.

The “Rumble in the Jungle” was filmed over five weeks in Machava Stadium, five kilometers northwest of Maputo. The stadium was used to host large international soccer tournaments but had fallen into disrepair — there wasn’t even any electricity. The production spent $100,000 repairing and upgrading the 64,000-seat capacity stadium. They structurally engineered and replicated a ring and canopy that was 40 feet high, 82 feet wide and weighed over 40 tons. Over 10,000 extras were needed for the scene where Ali makes his entrance into the stadium. Fliers were distributed in Maputo inviting people to watch the filming. The production also cast 2,000 extras that would be costumed and fill seats on the floor around the ring. On the night of the scene, over 30,000 people showed up.

Known mostly for mindless, yet entertaining action films like Bad Boys (1995) and Independence Day (1996), Will Smith was not exactly most people’s first choice to play Muhammad Ali. However, Smith shows that he has the capacity for more substantial work with Six Degrees of Separation (1993) but he had never attempted anything as challenging as this project. Smith captures Ali’s distinctive speech patterns, especially his flamboyant, larger-than-life public persona. Like Anthony Hopkins before him in Nixon (1995), Smith does not look exactly like the actual person he is playing. Instead, he manages to capture the essence and the spirit of the man. He also does a good job of conveying Ali’s conflict between his loyalty to Islam and to his family and friends. Smith peels back the layers to show that there was so much more than Ali’s flashy public side. For example, most people only saw Ali and Cosell as antagonists, but this was only for show. In fact, they were good friends and the sportscaster was willing to help him out in any way possible.

While Smith was praised for his impressive physical transformation into legendary boxer Muhammed Ali, the film itself was criticized for revealing nothing new about the man. Herein lies the problem that Mann and company faced: how do you shed new light on one of the most documented historical figures of the 20th Century? Ali eschews the traditional docudrama for a more impressionistic take on the man and life. Mann’s film may not say anything new about the famous boxer, but it does depict an exciting ten years of his life in a masterful and richly evocative fashion. It’s a surprisingly soulful take on Ali and an excellent addition to Mann’s impressive body of work.

While Smith was praised for his impressive physical transformation into legendary boxer Muhammed Ali, the film itself was criticized for revealing nothing new about the man. Herein lies the problem that Mann and company faced: how do you shed new light on one of the most documented historical figures of the 20th Century? Ali eschews the traditional docudrama for a more impressionistic take on the man and life. Mann’s film may not say anything new about the famous boxer, but it does depict an exciting ten years of his life in a masterful and richly evocative fashion. It’s a surprisingly soulful take on Ali and an excellent addition to Mann’s impressive body of work.

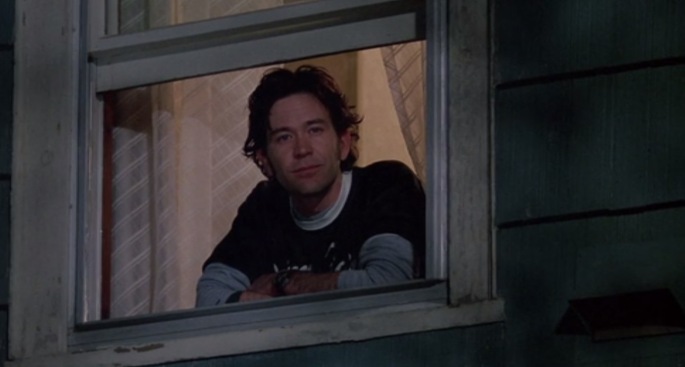

In the ‘80s, William Atherton seemed to be the go-to guy for playing douchebag authority figures, with memorable turns as the unscrupulous journalist in Die Hard (1988), the “dickless” EPA guy in Ghostbusters (1984), and, of course, his turn in Real Genius. Atherton’s job, and man, does he do it oh so well, is to provide a source of conflict for our protagonists. He portrays Hathaway as the ultimate arrogant prick and we can’t wait to see him get his well-deserved comeuppance at the hands of Chris and Mitch.

In the ‘80s, William Atherton seemed to be the go-to guy for playing douchebag authority figures, with memorable turns as the unscrupulous journalist in Die Hard (1988), the “dickless” EPA guy in Ghostbusters (1984), and, of course, his turn in Real Genius. Atherton’s job, and man, does he do it oh so well, is to provide a source of conflict for our protagonists. He portrays Hathaway as the ultimate arrogant prick and we can’t wait to see him get his well-deserved comeuppance at the hands of Chris and Mitch. Real Genius argues that nerds can have fun too, but there needs to be a balance. You can love solving problems but it can’t be all science and no philosophy as Chris tells Mitch. People like Kent and Hathaway have no sense of humor and are self-obsessed egotists. They are ambitious to a fault, not caring who they step on the way, while Chris and Mitch are aware of the consequences of their actions. There is sweetness to this film that is endearing and rather strange considering that Neal Israel and Pat Proft wrote the screenplay (authors of such paeans to sweetness, like Police Academy and Bachelor Party), but Coolidge is firmly in charge and wisely doesn’t let Real Genius get too sappy. She also doesn’t let the funny stuff devolve into mindless frat humor, instead maintaining a proper mix that doesn’t insult our intelligence. The end result is a film that the characters in the film might enjoy, if they weren’t already in it. Achieving just the right alchemy may explain why the film continues to enjoy a modest cult following and is one of the few teen comedies from the ‘80s that stands the test of time.

Real Genius argues that nerds can have fun too, but there needs to be a balance. You can love solving problems but it can’t be all science and no philosophy as Chris tells Mitch. People like Kent and Hathaway have no sense of humor and are self-obsessed egotists. They are ambitious to a fault, not caring who they step on the way, while Chris and Mitch are aware of the consequences of their actions. There is sweetness to this film that is endearing and rather strange considering that Neal Israel and Pat Proft wrote the screenplay (authors of such paeans to sweetness, like Police Academy and Bachelor Party), but Coolidge is firmly in charge and wisely doesn’t let Real Genius get too sappy. She also doesn’t let the funny stuff devolve into mindless frat humor, instead maintaining a proper mix that doesn’t insult our intelligence. The end result is a film that the characters in the film might enjoy, if they weren’t already in it. Achieving just the right alchemy may explain why the film continues to enjoy a modest cult following and is one of the few teen comedies from the ‘80s that stands the test of time.

Amazingly, Tron wasn’t even nominated for a special effects Academy Award because “the Academy thought we cheated by using computers,” Lisberger remembers. However, his film and the world he and his team created captivated a small group of moviegoers. A loyal cult following developed around Tron over the years. The film may have not captured the public consciousness when it first came out but it has since developed a loyal following that loves it dearly. In many respects, Tron is a snapshot of the early ’80s when video games were just starting to take off, but it also was a harbinger of things to come. It paved the way for the elaborate computer graphics we see in movies like The Matrix (1999) and the new Star Wars movies. However, Tron warns that we cannot rely totally on computers to do everything because in doing so we run the risk of losing our humanity. I always imagine Flynn going on to become Bill Gates or maybe Steve Jobs.

Amazingly, Tron wasn’t even nominated for a special effects Academy Award because “the Academy thought we cheated by using computers,” Lisberger remembers. However, his film and the world he and his team created captivated a small group of moviegoers. A loyal cult following developed around Tron over the years. The film may have not captured the public consciousness when it first came out but it has since developed a loyal following that loves it dearly. In many respects, Tron is a snapshot of the early ’80s when video games were just starting to take off, but it also was a harbinger of things to come. It paved the way for the elaborate computer graphics we see in movies like The Matrix (1999) and the new Star Wars movies. However, Tron warns that we cannot rely totally on computers to do everything because in doing so we run the risk of losing our humanity. I always imagine Flynn going on to become Bill Gates or maybe Steve Jobs.

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo.

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo. The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.

The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.

The focus on the years 1964 to 1974 are arguably the most fascinating ones of Ali’s life because they are so rife with dramatic possibilities. It was during this period that Ali became the World Boxing Champion after beating Sonny Liston, then lost it when he refused to serve as a foot soldier in the Vietnam War, and finally reclaimed the Championship Title after beating the odds-on favorite, George Foreman in Zaire. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval in the United States with the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Finally, Ali also shows the man’s private side: his numerous wives and failed marriages, and his friendships with Malcolm X and Howard Cosell.

The focus on the years 1964 to 1974 are arguably the most fascinating ones of Ali’s life because they are so rife with dramatic possibilities. It was during this period that Ali became the World Boxing Champion after beating Sonny Liston, then lost it when he refused to serve as a foot soldier in the Vietnam War, and finally reclaimed the Championship Title after beating the odds-on favorite, George Foreman in Zaire. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval in the United States with the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Finally, Ali also shows the man’s private side: his numerous wives and failed marriages, and his friendships with Malcolm X and Howard Cosell. While Smith was praised for his impressive physical transformation into legendary boxer Muhammed Ali, the film itself was criticized for revealing nothing new about the man. Herein lies the problem that Mann and company faced: how do you shed new light on one of the most documented historical figures of the 20th Century? Ali eschews the traditional docudrama for a more impressionistic take on the man and life. Mann’s film may not say anything new about the famous boxer, but it does depict an exciting ten years of his life in a masterful and richly evocative fashion. It’s a surprisingly soulful take on Ali and an excellent addition to Mann’s impressive body of work.

While Smith was praised for his impressive physical transformation into legendary boxer Muhammed Ali, the film itself was criticized for revealing nothing new about the man. Herein lies the problem that Mann and company faced: how do you shed new light on one of the most documented historical figures of the 20th Century? Ali eschews the traditional docudrama for a more impressionistic take on the man and life. Mann’s film may not say anything new about the famous boxer, but it does depict an exciting ten years of his life in a masterful and richly evocative fashion. It’s a surprisingly soulful take on Ali and an excellent addition to Mann’s impressive body of work.

Megaforce is the best movie in the world… when you’re a nine-year-old kid with no critical faculties and just want to see stuff blow up, like I did back in 1982. As a kid I loved this movie for the simple reason that it was a live-action version of the T.V. cartoon/toy I was obsessed with at the time – G.I. JOE: A Real American Hero. Both feature a secretive army populated by specialists armed with hi-tech gear, fighting evil all over the world. They eventually made a live-action G.I. JOE movie in 2009 (with a sequel on the way) but, for me, it pales in comparison to Megaforce, which for all of its inherent cheesiness feels like it was the product of a deluded madman – Needham – and not a badly made by committee, CGI-heavy advertisement for toys.

Megaforce is the best movie in the world… when you’re a nine-year-old kid with no critical faculties and just want to see stuff blow up, like I did back in 1982. As a kid I loved this movie for the simple reason that it was a live-action version of the T.V. cartoon/toy I was obsessed with at the time – G.I. JOE: A Real American Hero. Both feature a secretive army populated by specialists armed with hi-tech gear, fighting evil all over the world. They eventually made a live-action G.I. JOE movie in 2009 (with a sequel on the way) but, for me, it pales in comparison to Megaforce, which for all of its inherent cheesiness feels like it was the product of a deluded madman – Needham – and not a badly made by committee, CGI-heavy advertisement for toys.

Kasdan’s ability to engage us in the obligatory exposition scene is evident early when Indy and his friend and colleague Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott) meet with two military intelligence officers about the location of an old colleague of Indy’s – Abner Ravenwood – who might have an artifact – the headpiece of the Staff of Ra – that will reveal the location of the Ark of the Covenant, which the Nazis are eager to get their hands on. Indy and Marcus give the two men a quick history lesson on the Ark and its power. Marcus concludes with the ominous line about how the city of Tanis, that reportedly housed the Ark, “was consumed by the desert in a sandstorm which lasted a whole year. Wiped clean by the wrath of God.” The way Denholm Elliott delivers this last bit is a tad spooky and is important because it lets us know of the Ark’s power, his reverence for it, and why the Nazis are so interested in it. This dialogue also gives us an indication of the kind of danger that Indy is up against.

Kasdan’s ability to engage us in the obligatory exposition scene is evident early when Indy and his friend and colleague Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott) meet with two military intelligence officers about the location of an old colleague of Indy’s – Abner Ravenwood – who might have an artifact – the headpiece of the Staff of Ra – that will reveal the location of the Ark of the Covenant, which the Nazis are eager to get their hands on. Indy and Marcus give the two men a quick history lesson on the Ark and its power. Marcus concludes with the ominous line about how the city of Tanis, that reportedly housed the Ark, “was consumed by the desert in a sandstorm which lasted a whole year. Wiped clean by the wrath of God.” The way Denholm Elliott delivers this last bit is a tad spooky and is important because it lets us know of the Ark’s power, his reverence for it, and why the Nazis are so interested in it. This dialogue also gives us an indication of the kind of danger that Indy is up against. This segues to a nice little scene right afterwards at Indy’s home between the archaeologist and Marcus. He tells Indy that the United States government wants him to find the headpiece and get the Ark. As Indy gets ready they talk about the Ark. The camera pans away from Indy packing to a worried Marcus sitting on a sofa and he reveals his apprehension about what his friend is going after: “For nearly 3,000 years man has been searching for the lost Ark. It’s not something to be taken lightly. No one knows its secrets. It’s like nothing you’ve ever gone after before.” Indy shrugs off Marcus’ warning but his words, accompanied by John Williams’ quietly unsettling score, suggest the potential danger Indy faces messing with forces greater and older than himself.

This segues to a nice little scene right afterwards at Indy’s home between the archaeologist and Marcus. He tells Indy that the United States government wants him to find the headpiece and get the Ark. As Indy gets ready they talk about the Ark. The camera pans away from Indy packing to a worried Marcus sitting on a sofa and he reveals his apprehension about what his friend is going after: “For nearly 3,000 years man has been searching for the lost Ark. It’s not something to be taken lightly. No one knows its secrets. It’s like nothing you’ve ever gone after before.” Indy shrugs off Marcus’ warning but his words, accompanied by John Williams’ quietly unsettling score, suggest the potential danger Indy faces messing with forces greater and older than himself. Kasdan also does a great job hinting at a rich backstory between Indy and his ex-love interest, Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). When they are reunited at a bar she runs in Nepal, she is clearly not too thrilled to see him, giving Indy a good crack on the jaw. Marion alludes to a relationship between them that went bad. She was young and in love with him and he broke her heart. To add insult to injury, her father is dead. All Indy can do is apologize as he says, “I can only say sorry so many times,” and she has that wonderful retort, “Well say it again anyway.” Harrison Ford and Karen Allen do a great job with this dialogue, suggesting a troubled past between them. In a nice touch, Spielberg ends the scene with Indy walking out the door. He takes one last look back and his face is mostly obscured in shadow in a rather ominous way as he clearly looks uncomfortable having had to dredge up a painful part of his past.

Kasdan also does a great job hinting at a rich backstory between Indy and his ex-love interest, Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). When they are reunited at a bar she runs in Nepal, she is clearly not too thrilled to see him, giving Indy a good crack on the jaw. Marion alludes to a relationship between them that went bad. She was young and in love with him and he broke her heart. To add insult to injury, her father is dead. All Indy can do is apologize as he says, “I can only say sorry so many times,” and she has that wonderful retort, “Well say it again anyway.” Harrison Ford and Karen Allen do a great job with this dialogue, suggesting a troubled past between them. In a nice touch, Spielberg ends the scene with Indy walking out the door. He takes one last look back and his face is mostly obscured in shadow in a rather ominous way as he clearly looks uncomfortable having had to dredge up a painful part of his past. Indy and Marion have another nice scene together after they’ve retrieved the Ark from the Nazis and are aboard the Bantu Wind, a tramp steamer that will take them to safety. Marion tends to Indy’s numerous wounds and says, “You’re not the man I knew ten years ago,” and he replies with that classic line, “It’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage.” It starts out as a playful scene as everything Marion does to help hurts Indy’s world-weary body. In frustration she asks him to show her where it doesn’t hurt and he points to various parts of his body and in a few seconds the scene goes from playful in tone to romantic as they end up kissing. Of course, Indy falls asleep – much to Marion’s chagrin. Kasdan’s dialogue gives Spielberg’s chaste, boyhood fantasy serial adventure a slight air of sophistication in this scene as two people with a checkered past finally reconnect emotionally.

Indy and Marion have another nice scene together after they’ve retrieved the Ark from the Nazis and are aboard the Bantu Wind, a tramp steamer that will take them to safety. Marion tends to Indy’s numerous wounds and says, “You’re not the man I knew ten years ago,” and he replies with that classic line, “It’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage.” It starts out as a playful scene as everything Marion does to help hurts Indy’s world-weary body. In frustration she asks him to show her where it doesn’t hurt and he points to various parts of his body and in a few seconds the scene goes from playful in tone to romantic as they end up kissing. Of course, Indy falls asleep – much to Marion’s chagrin. Kasdan’s dialogue gives Spielberg’s chaste, boyhood fantasy serial adventure a slight air of sophistication in this scene as two people with a checkered past finally reconnect emotionally. For me, Raiders is still the best film in the series. The pacing is fast but not as frenetic as today’s films. There are lulls where the audience can catch its breath and exposition is conveyed. In many respects, it is one of the best homages to the pulpy serials of the 1930s and a classic example of when all the right elements came together at just the right time. This film has aged considerably well over time and each time I see it, I still get that nostalgic twinge and still get sucked in to Indy’s adventures looking for the lost Ark.

For me, Raiders is still the best film in the series. The pacing is fast but not as frenetic as today’s films. There are lulls where the audience can catch its breath and exposition is conveyed. In many respects, it is one of the best homages to the pulpy serials of the 1930s and a classic example of when all the right elements came together at just the right time. This film has aged considerably well over time and each time I see it, I still get that nostalgic twinge and still get sucked in to Indy’s adventures looking for the lost Ark.

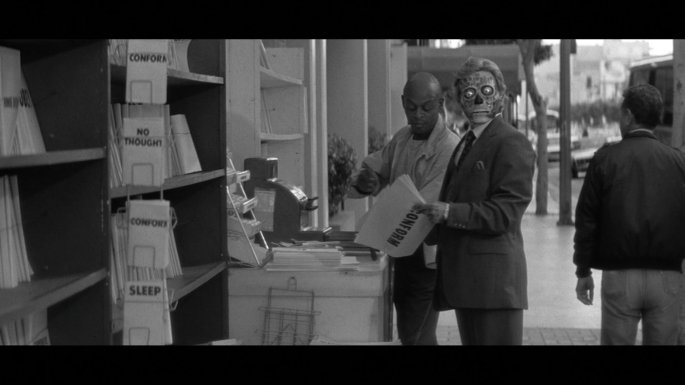

Carpenter sees the commercial failure of his film as a result of “people who go to the movies in vast numbers these days [who] don’t want to be enlightened.” It’s a shame because They Live is far from being an overtly preachy film. On the contrary, it is always exciting and entertaining first, and a scathingly social satire second. However, the director sees the real tragedy to be the lack of humanity in society. “The real threat is that we lose our humanity. We don’t care anymore about the homeless. We don’t care about anything, as long as we make money.” If They Live is about anything, it’s a strong indictment against the capitalist greed that was so fashionable in the 1980s. It’s sentiment that still exists. This makes Carpenter’s film just as relevant today as it was back in 1988.

Carpenter sees the commercial failure of his film as a result of “people who go to the movies in vast numbers these days [who] don’t want to be enlightened.” It’s a shame because They Live is far from being an overtly preachy film. On the contrary, it is always exciting and entertaining first, and a scathingly social satire second. However, the director sees the real tragedy to be the lack of humanity in society. “The real threat is that we lose our humanity. We don’t care anymore about the homeless. We don’t care about anything, as long as we make money.” If They Live is about anything, it’s a strong indictment against the capitalist greed that was so fashionable in the 1980s. It’s sentiment that still exists. This makes Carpenter’s film just as relevant today as it was back in 1988.

American critics underestimated the widespread influence it has had since its initial release. A much imitated (see The Hidden amongst many others) film, it still manages to captivate and delight people today. The film has been read on many different levels, most often as a subtext for protesting Senator Joseph McCarthy and his Red Scare mentality or as an anti-Communist allegory. First and foremost it is an entertaining film that blends a science fiction premise with film noir and horror elements (in particular, its use of unusual camera angles, close-ups, sharp editing, music, and lighting). Despite three remakes, the original film is the superior version because its director, Don Siegel understood Finney’s novel and was able to translate its intent successfully to the screen without relying on flashy special effects and trickery like so many contemporary science fiction films.

American critics underestimated the widespread influence it has had since its initial release. A much imitated (see The Hidden amongst many others) film, it still manages to captivate and delight people today. The film has been read on many different levels, most often as a subtext for protesting Senator Joseph McCarthy and his Red Scare mentality or as an anti-Communist allegory. First and foremost it is an entertaining film that blends a science fiction premise with film noir and horror elements (in particular, its use of unusual camera angles, close-ups, sharp editing, music, and lighting). Despite three remakes, the original film is the superior version because its director, Don Siegel understood Finney’s novel and was able to translate its intent successfully to the screen without relying on flashy special effects and trickery like so many contemporary science fiction films.