The 1970s was a fertile time for challenging, politically charged movies. Thanks to Easy Rider (1969) a lot of riskier material was getting made by the major Hollywood studios and, in some cases, they were commenting on the current political climate and being socially conscious. One of the best examples from this decade is All the President’s Men (1976) – the Citizen Kane (1941) of investigative journalism films. It’s the benchmark by which all other films of its genre are compared to, from The China Syndrome (1979) to State of Play (2009). Its influence can be felt in the films of Steven Soderbergh (Traffic) and David Fincher (Zodiac).

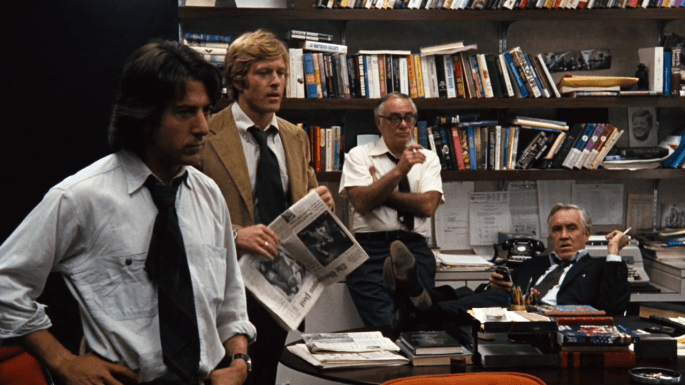

All the President’s Men was immediate and topical, dramatizing Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s investigation of the Watergate Hotel burglary and the resulting scandal that would rock the White House and forever taint President Richard Nixon’s tenure there, effectively sending him home packing before his term was up. Alan J. Pakula’s film struck a chord with audiences of the day (and continues to do so) and is credited with inspiring future generations of journalists. Of course, it didn’t hurt that the film starred Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford, two of the biggest movie stars in Hollywood at that time. Fortunately, they left their egos at the door to deliver thoughtful and intense performances. These are complemented by Pakula’s no frills direction and Gordon Willis’ moody, atmospheric cinematography.

The film begins, rather fittingly, with the actual break-in. We see the burglars at work in the gloom of the hotel, often from a distance which, somehow makes it actually creepier than it should. Pakula juxtaposes this with the next scene, which takes place in the brightly-lit offices of the Washington Post. Bob Woodward (Redford) gets the tip about the burglars and goes to see the charges brought up against them in front of a judge. It is here that he meets the first of many people that will try to stonewall him. Woodward starts talking to a man named Markham (Nicolas Coster) sitting in front of him. He tells Woodward that he’s not there as the attorney of record but reveals who that is and leaves. Woodward follows Markham outside into the hallway and continues to question him. Markham tries to confuse and evade Woodward through dialogue and while not actually saying much of anything he does pique the reporter’s curiosity.

Back at the Washington Post offices, Woodward meets with his editor Harry Rosenfeld (Jack Warden) and fellow reporter Carl Bernstein (Hoffman) who has been calling around getting information of his own. However, neither of them have much and Rosenfeld calls them on it: “I’m not interested in what you think is obvious. I’m interested in what you know.” One of the things that is so great about All the President’s Men is that they show the legwork these guys do in order to get the facts and the details to flesh out their articles. For example, there’s the scene where Woodward calls around trying to find out who Howard Hunt is and his relation to the White House. Pakula has Redford in the foreground but utilizes deep focus photography so that we can make out the hustle and bustle in the middle and background of the scene, which is a nice touch. It makes the scene more than just about dialogue and about what’s being said as Pakula keeps things visually interesting.

The way Woodward and Bernstein team-up is also well done. Woodward hands in a copy of his article to be proofread only for Bernstein to immediately take it and give it a polish. Woodward is upset at Bernstein for doing it without his permission, gives him his notes and says, “If you’re going to hype it, hype it with the facts. I don’t mind what you did. I mind the way you did it.” In an amusing bit, right after he says this, Rosenfeld walks by and tells them that they’re working together on the Watergate story. Early on, Woodward and Bernstein know that they are onto something and the more people evade them or deny any kind of knowledge of what went down at the Watergate, the more they realize that they’re onto something big. I also like that once they team-up, Pakula doesn’t try to make them too buddy-buddy. They work closely together but it is purely professional. They don’t hang out together or go to nightclubs. They are completely consumed by their investigation and getting to the truth.

Woodward and Bernstein show their story to the newspaper’s executive editor Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards) and the way he picks apart their article is devastating, especially if you’ve ever worked at a newspaper or a magazine. But, deep down, they know he’s right – they don’t have the story or the hard facts to back it up. Woodward and Bernstein approach every contact they know that might have even the most remote connection to their investigation. But they are persistent and keep plugging away at the story.

For a film that is ostensibly about two guys talking on the phone and interviewing people, All the President’s Men is always interesting to watch because of Pakula’s no-nonsense direction coupled with Gordon Willis’ textured cinematography. We get one engaging visual after another, like the scene where Woodward and Bernstein pour over index cards at the Library of Congress and the camera starts off with a tight overhead shot of them and then gradually pulls back to reveal the circular design of the building while also showing how insignificant these two men are in comparison to the task they are undertaking. In addition, Woodward’s meetings with his enigmatic informant known only as Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook) in a deserted parking garage at night illustrates why Willis was often referred to as the “Prince of Darkness.” We first see Deep Throat in the distance, enshrouded in darkness. He briefly lights a cigarette that does little to illuminate his identity. Even when shot in close-up, he’s still mostly in shadow except for a very film noirish strip of dim light across his face so that we can at least see his eyes. This emphasizes the ominous nature of this clandestine meeting. Never has a parking garage looked so menacing.

Another visually interesting phone scene has Woodward doing some more legwork at his desk. As he’s talking, off to the left in the background, a group of people are watching something on television. As the scene continues, the camera ever-so gradually moves in on Woodward until a close-up of his face dominates the screen. Pakula flips this in another scene where we get a close-up shot of a T.V. covering Nixon getting voted into the White House for four more years while in the background Woodward works away on the story. The juxtaposition of visuals is particularly striking as the T.V. absolutely dwarfs Woodward symbolizing just how marginalized he is in comparison to Nixon. He has regained the most powerful position in the free world while Woodward is still trying to get some decent facts. Willis’ lighting goes beyond adventurous as he continually pushes the boundaries of available light. For example, there’s a scene where Woodward and Bernstein have a conversation while driving in a car at night and it looks like the scene was done with only naturally available light. There are significant portions of the scene where we can barely or not see Woodward and Bernstein. You would never see that in a mainstream studio film today as it goes against the conventional wisdom of making sure the audience can always see the heroes clearly.

It goes without saying that All the President’s Men features an impressive cast. Redford and Hoffman do a good job showing the incredible pressure that Woodward and Bernstein are under. Not only are they trying to find people to go on the record but are also trying to prove to their editors that they are doing a good job and deserve to be on this story. In addition, they also have to make sure that a rival newspaper like The New York Times doesn’t scoop them first. Redford and Hoffman are not afraid to show the friction that sometimes surfaces between Woodward and Bernstein, especially when they hit dead ends in their investigation. Their frustrations come out as they try to get someone to go on record and give them some crucial information that they can use.

Supporting Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford are the likes of Jack Warden, Jason Robards, Martin Balsam, and Hal Holbrook who bring their real life counterparts to the big screen in such compelling fashion. Robards brings just the right amount of world-weary gravitas necessary to play someone like Ben Bradlee. He plays the editor as the gruff father-figure that gives Woodward and Bernstein tough love and in doing so pushes them to work harder and dig deeper on the Watergate story. There’s a nice scene where Bradlee sits down with the two reporters and recounts a story about how he covered J. Edgar Hoover being announced as head of the FBI. The story and how Robards tells it humanizes Bradlee and makes him relatable to Woodward and Bernstein.

Hal Holbrook is coolly enigmatic as the shadowy Deep Throat, giving Woodward cryptic clues and vague encouragement. His brief but memorable appearance would go on to inspire like-minded characters in Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991) and the popular T.V. series The X-Files. And, if you look close enough, a young and very good-looking Lindsay Crouse plays a Washington Post office worker that helps out Woodward and Bernstein. Also, look for Stephen Collins, Ned Beatty and Jane Alexander in small but memorable roles.

From the age of 13, Robert Redford disliked Richard Nixon after meeting the man at a tennis tournament when he was only a senator. These feelings persisted when Nixon became vice-president and during his first term as president. While promoting The Candidate in July 1972, Redford became aware of Woodward and Bernstein’s articles in the Washington Post documenting the break-in at the Watergate Hotel. Four Cuban-Americans and CIA employee James McCord broke in and burglarized the Democratic Party’s headquarters. It was later revealed that they were funded by the Republican Party. Redford asked various reporters on his promotional tour why they weren’t covering the Watergate break-in and he was met with cynicism and condescension.

After his promo duties ended, Redford returned home and continued to follow Woodward and Bernstein’s progress in the Washington Post. In October 1972, Redford read a profile about the two reporters and began thinking about making a film about them. His original notion was to make a low-budget, black and white film with two unknown actors and he would produce it. Redford tried to contact Woodward and Bernstein but they did not return his calls. He tried again six weeks later while making The Way We Were (1973) but was rebuffed by them and decided to shelve the project.

In April 1973, a link between the burglars and the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP) was uncovered and all of Woodward and Bernstein’s hard work had finally paid off. Redford contacted Woodward again and was able to convince him to meet the next day in Washington, D.C. Redford pitched his idea and passion for the project and Woodward agreed to meet him, along with Bernstein, at the actor’s apartment in New York City. Redford told his friend, and screenwriter William Goldman about the meeting and he asked the actor if he could tag along. Redford agreed and in February 1974, they met with Woodward and Bernstein. They told Redford and Goldman that they were about to expose, and thereby cause the resignations of, chief of staff H.R. Haldeman, assistant for domestic affairs to the president, John Ehrlichman, and Nixon’s lawyer, John Dean.

Redford asked Woodward and Bernstein for the film rights to their investigation of the Watergate Hotel burglary but they were hesitant to do so and told him that they were working on a book. He told them that the film would focus on the early stages of their investigation. He said, “the part I’m interested in is not the aftermath so much as what happened when no one was looking. Because that’s what no one knows about.” Redford also wanted to tell the story from Woodward and Bernstein’s point-of-view. They agreed to give him the film rights but with the stipulation that work on it could not begin until they completed the book in eight or nine month’s time. During this time, Nixon resigned and “an amazing story unfolded while I was waiting to do this movie,” Redford said.

The book’s publisher, Simon & Schuster, demanded $450,000 for the film rights which was a very high price at the time. Redford’s dream of a low-budget film with unknowns was no longer possible and so he had Warner Brothers raise $4 million while his production company, Wildwood Productions, contributed another $4 million. As a result, the studio insisted that All the President’s Men would be a commercial film and that Redford would have to agree to be in it. He still wanted Woodward and Bernstein to be played by unknown actors but the studio refused and the actor would have to play Woodward. So that Bernstein would not be overshadowed as a result, an actor of equal star power would have to be cast opposite Redford and Dustin Hoffman was hired for the role.

William Goldman wrote a draft of the screenplay that Redford was not thrilled about: “Goldman writes for cleverness and was still leaning all over Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. He was borrowing heavily from the charm of that piece and it didn’t work. It was written very quickly, and it went for comedy. It trivialized not only the event but journalism.” The actor wanted Elia Kazan to direct the film but the veteran filmmaker did not like it either and turned down Redford’s offer. Next, he approached William Friedkin because Redford felt that the film needed “a visceral kind of emotional energy, and Friedkin had that.” The director actually liked Goldman’s script but felt that he was the wrong person for the job. Bernstein also joined the ever-increasing list of people who did not like what Goldman had written and with then-girlfriend Nora Ephron, wrote his own draft. Not surprisingly, their version had Bernstein as a dashing, heroic figure while Woodward was a passive follower. Redford was unaware that Bernstein was doing this and when he read their draft he realized that too much emphasis had been placed on Bernstein and rejected it.

Impressed with his work on Klute (1971), Redford asked Alan J. Pakula if he would like to direct All the President’s Men. Initially, the actor was worried that Pakula was too cerebral a filmmaker and lacked the visceral edge that he wanted for the film but when he met with him, Redford “felt so comfortable about our ability to communicate that I just decided to go for it.” Pakula read Goldman’s script and, big surprise, did not like it (these also included executives at the Washington Post). In order to prepare for the film, Pakula spent more than a month hanging out at the Post offices observing the daily routines of the editors and reporters. In addition, he hung out with Bradlee for three days, joining him on phone conversations and news conferences. Afterwards, he insisted that Goldman’s script be rewritten and the lighthearted tone changed. Redford spoke to Goldman and told him that he had to work on the script more and spend time in Washington, D.C. and, in particular, at the Post. However, the actor found out that Goldman was also writing Marathon Man (1976) and realized that the screenwriter would not be devoting the time needed for the All the President’s Men’s script. He confronted Goldman over the issue and the two men had a falling out over the script. In his defense, Goldman claimed that Pakula was “unable to make up his mind” when it came to discussing scenes in the script and as a result he was unable to write productively.

Pakula and Redford checked into the Madison Hotel in D.C. and spent a month rewriting the script themselves. During this process, Woodward and Bernstein turned over all their notes to Redford and Pakula who used them as the basis for their treatment. Redford said, “we were literally able to take these notes and construct a kind of through-line of their investigation.” Ultimately, they used the structure Goldman had created for the script and discarded most of the rest.

Originally, Pakula and Redford had hoped to shoot All the President’s Men in the offices of the Washington Post and use actual employees as characters in the film but the newspaper’s publisher denied them access and was afraid that it would destroy the periodical’s reputation. A replica of the Post’s newsroom was built on two large soundstages at the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, California at a cost of $450,000. This put a strain on the budget forcing three planned scenes to be cut. However, the Post offices were recreated in the most exact detail. Around 200 desks were ordered from the company that the Post also used. They were then painted in exactly the same color as the real desks. The attention to detail is incredible as the offices of the newspaper look, sound and feel like an authentic newsroom.

Principal photography began on May 12, 1975. Early on, Redford had difficulty portraying Woodward because he found him to be a “boring guy. He’s not the most exciting guy in the world to play, and I can’t get a grip on the guy because he’s so careful and hidden.” Pakula told Redford, “you’ve got to concentrate and you’ve got to think, and the audience has got to be able to see you think and they’ve got to be able to feel your concentration.” The director noticed that for awhile Redford was uncomfortable in the role and was frustrated trying to get a handle on the character. Pakula used this to his advantage early on in filming to convey a more reserved and controlled Woodward. Once Redford got comfortable in the role, Pakula filmed his scenes in the newsroom and saw that the actor’s concentration had improved.

Pakula does the seemingly impossibly by making what is essentially a film about people talking and make it incredibly compelling. This is because of the material and the actors that bring it to life. With the help of Willis’ camerawork, Pakula keeps things visually interesting. This is not an easy thing to pull off and may explain why there aren’t many good journalism films like this one. And that’s because you run the danger of getting bogged down by excessive expositional dialogue that tells us too much instead of showing us. Or, the filmmakers try and spice things up with clichéd genre conventions like a car chase or a shoot-out. Pakula’s film also doesn’t rely on an overtly dramatic score that tells us what to feel. David Shire’s score is refreshingly minimalist and used sparingly by the director. What makes the film work so well is that it shows all the hard, tedious legwork that Woodward and Bernstein had to do in order to break the case: countless phone calls and knocking on doors trying to get anybody remotely linked to the burglary or those arrested to talk. All the President’s Men was a watershed film that would go on to inspire other hard-hitting, investigative journalism movies like The Insider (1999) and Shattered Glass (2003).