Tracing his incremental steps that ultimately led to theatrical features, it makes sense that Michael Mann would create his first feature film for network television. Coming off two paying gigs that made 1978 a pivotal year for the filmmaker (namely his uncredited work on Ulu Grosbard’s Straight Time and his credited creation of the television series VEGA$ by way of the Mann-scripted pilot), he was a natural fit to write The Jericho Mile, a movie-of-the-week for ABC. Hired directly by actor Peter Strauss, Mann’s script impressed Strauss so much that he convinced the network to allow Mann to direct. After bouncing around Hollywood for a while and writing scripts for television (not to mention having the creation of a whole show on his resume), Mann was definitely due. And Strauss, insanely popular throughout the seventies due to his appearance in Rich Man, Poor Man, had the kind of stroke to make it happen.

The Jericho Mile was prime material for Mann. A healthy blend of the prison film and the sports drama, the film follows lifer inmate Rain Murphy (Strauss) as he uses long distance running as a means of coping with the confines of prison and his inability to steer the direction of his life. As his prison counselor notices the incredible speed in which Murphy can clear a mile, a succession of events occur in which Murphy is given the opportunity to compete for a spot on the Olympic team while he also navigates the tricky and sometimes lethal political structure within the prison.

It is the latter where The Jericho Mile truly excels, at times feeling entirely authentic as the convicts with speaking roles mesh alongside the professional actors. Additionally, a great deal of value is generated by shooting within the walls of California’s Folsom Prison. The metal works, the kitchen, laundry room, the yard, and the squat, desolate cells go a great distance in selling the film’s credibility and reflecting a world that is cramped and oppressive. This last element is also helped immeasurably by its boxy 1.33:1 aspect ratio, standard for television broadcasts of the day, which now makes the film look especially claustrophobic and tight.

The film should also be commended for what it doesn’t do. While it can’t help but traffic in some of the hoariest tropes of the prison film (which may or may not be its fault since there are only a limited number of things that can occur in prison), it doesn’t stoop to underlining the explicit inhumanity that occurs in confinement. Instead of shocking viewers with lurid details (which was actually pretty much par for the course in the day), the film wisely keeps within the boundaries of taste and shows how prisoners are generally in an impossible double-bind with both the state and the prison population, the structure of the latter being as complicated, unfair, and unforgiving as the bureaucratic red tape and regulations that routinely crush the spirits of the incarcerated. Additionally, the film doesn’t introduce a doomed relationship into Murphy’s life and, instead, keeps his one encounter with the opposite gender to be that of a brief glance between himself and an executive assistant at the U.S. Olympic board, reminding him of his status as someone with zero future with her or with anyone else but himself and what’s in his head.

To this end, The Jericho Mile has a wise, knowing angle on the life of the career criminal and prisoner. Whether or not this is due to Mann’s familiarity with the Edward Bunker material that became the screenplay for Straight Time is uncertain, but it’s likely. The transcendent poeticism meshing with the gritty details feels very much like Bunker’s outward expression of the criminal life as a certain kind of art form but the level of stoic control in Murphy’s character is all Mann. Murphy is Max Dembo if Dembo was remanded back to the state pen and took up long distance running, speaking with a clear, direct cadence with very few consonants, most reminiscent of James Caan’s Frank in Thief. This is why The Jericho Mile also stands as an almost reference point for the vast majority of Mann’s other criminal protagonists that would come later. Certainly both Frank and Neil McCauley’s talk about prison and doing time harkens back to the life we see unfold in The Jericho Mile where the only time we leave the prison walls to get a sense of real freedom is when Murphy is allowed to run around the parameter of them while in training. The reasoning behind the reluctance for later Mann characters to want to go back into a hell on earth is made strikingly clear in this film and, once he’s out, Mann rarely ever takes his cameras, or his characters, back in.

Being a television movie, the film sometimes falls into traps that reveals its limited hand. Where it doesn’t feel as sanded down in terms of the language or the prison violence (though it is on both counts), Mann’s preoccupation with lacing his drama with broad, emotion-driven moments is met with the medium’s small scale causing passages that might play a little more successfully on larger-than-life movie theater screens. This is most evident with the hotted-up performance by Brian Dennehy as Dr. D, the leader of the neo-Nazi faction of the prison, and with Richard Lawson’s performance as the doomed inmate, Stiles. For both, the screen size seems an ill fit to their grander, almost stage-bound turns. Mann often lets his actors descend into a sort of archness (specifically Tom Cruise’s Vincent in Collateral and literally everyone in his theatrical adaptation of Miami Vice) where the characters play to both the dunderheads AND the back row, but those performances need to be accompanied by a bigness and a freedom that a made-for-television movie produced in 1979 is just not going to be able to allow.

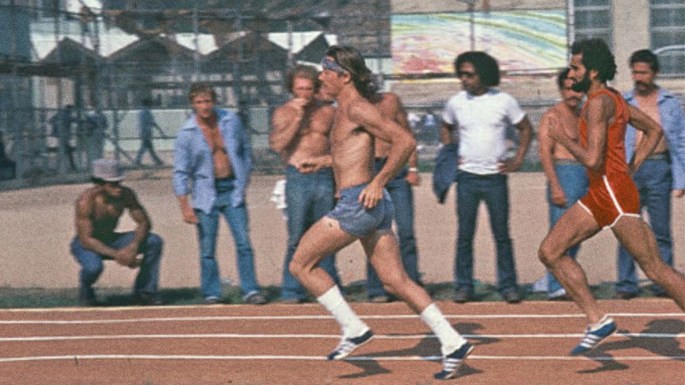

Also less successful, though not fatally, is the film’s sports angle. Again, there can really be no suspense as to how any of this is going to work out so the actual moments of Murphy running, training, and racing are less interesting than the passages that explore the reasons for his running. Unfortunately, the hook of the film is in its plotted narrative so the main thrust of the movie is, in fact, that of a rote sports film. Mann’s attempt to turn Murphy into a hopeful symbol both by and for the inmates may anticipate his approach to the material he would later take with Ali but here it feels a little undercooked. Despite Strauss’s emotional reaction to it, the moment where the prisoners line up to give him food for his training feels like a lachrymose, reverse-Cool Hand Luke, hitting the chords it wants to but not hitting them like it should.

For the most part, The Jericho Mile is an absolute triumph and, in fact, made a pretty big splash with audiences and critics at the time. Peter Strauss is utterly fantastic and won an Emmy for his role while Mann and co-writer Patrick Nolan picked up Emmys for their script. But most importantly, it gave Michael Mann his first stab at assembling a feature while also allowing him to work in the milieu that would inform his characters and their collective worldview throughout the rest of his career.

(C) Copyright 2021, Patrick Crain