There was a time when the artistry we see on the big screen was not generated by computers. There was a time when it was all hands-on; when talented artists and crafts people, put their skills to the test and pushed the limits of what was possible. They were behind the cameras and used techniques that are slowly fading from existence. They helped bring the director’s vision to life and excited audiences around the globe. Theirs was an art born of light and magic, of pain and patience in the aid of achieving wonders that still hold up to this day.

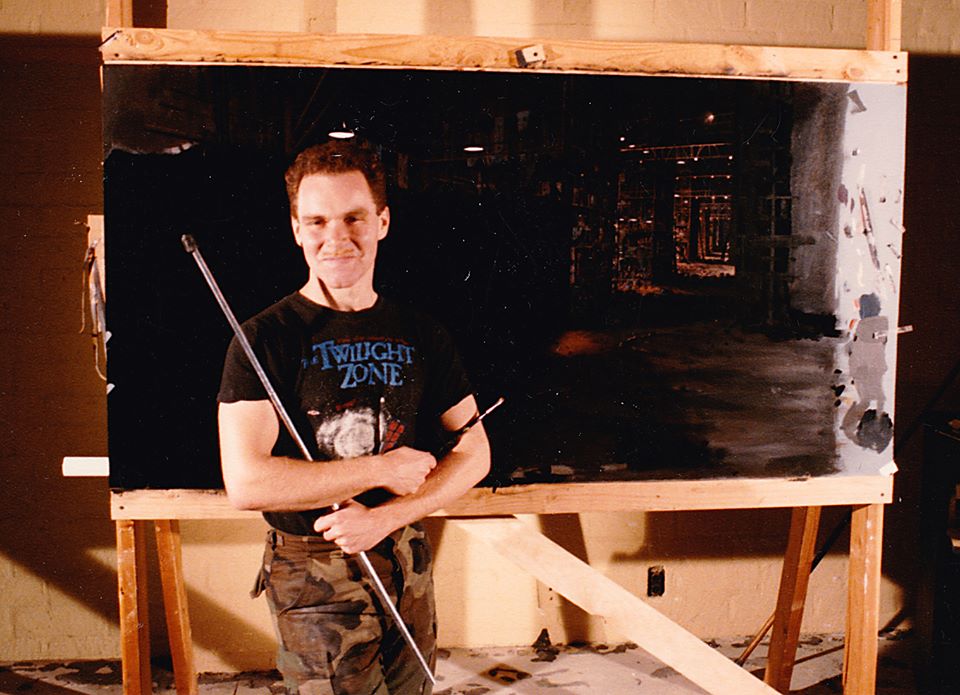

I recently had the good fortune to talk with one of these extraordinary artists. A man, who with his brush helped bring scenes to life in movies and television, from Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Game of Thrones. It was my pleasure to talk with the Hollywood veteran: Rocco Gioffre.

You may never have seen his face, but you have certainly scene his work – but as he might say; if the work is done well, you probably can’t see where the real world ends and the illusion begins.

KH: Now you’ve worked on some big movies. You’ve worked on everything from Spielberg films to Steven Seagal movies – even Beverly Hills Chihuahua?

RG: (laughter) You know, as the years go by, I find myself more and more, less in contact with the fellows who were directing the movies, basically further away on the totem pole, because there are many more visual effects supervisors involved in the making of big effects features these days, and so matte painters, especially since the advent of digital matte painting, have been replaced by people in ever increasing numbers who can operate Photoshop software efficiently, and you know, they do a lot of digital matte paintings in the movies these days, I’d say there are hundreds of what is considered qualified matte painting artists that operate as digital artists these days. So I think that, with some exceptions, like the film I just recently finished working on where I was hired to one, big, old, traditional matte painting, it was on a show called La La Land, and Damien Chazelle the young director who did Whiplash a couple of years ago, has just finished this up and it’s a musical with Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone, and I was actually contacted by a recommendation by another old-time matte painting artist who was of the last generation of paint brush matte artists, gave them my name because the director on this La La Land movie Damien Chazelle wanted a traditional brush-painted painting in his movie, because he wanted to impart some style, he actually wanted to see brush strokes on the thing, so that’s unique, but typically I’m working in digital now. The crews are gigantic. The likelihood of me working one on one with the director is not as common as it was in the old days.

KH: But you, you come from the classic school, you are one of the guys we see on old ‘making of’ books and publications painting on glass?

RG: Oh yes, that’s correct. I painted on glass, I think in those books and the way that people think of it, they think that the majority of these paintings were done on glass, where in fact when I go back and look at the actual art pieces that are left over from a variety of movies, a good percentage of those paintings were actually done on panel, hard board panel as well.

KH: I guess it would depend on whether or not there were live action elements which had to be composited together with the matte painting?

RG: Sure, although the ones that I’m referring to that are done on hard panel, the way that they are used in compositing, it’s the same kind of a thing where you think you might need to use a sheet of glass if you’re going to do a composite with live action photography, but more often than not it would be depending upon the methods chosen by the studio, because most of the panel matte paintings that I’m referring to, ones that were done on panel as well as ones that were done at say for instance MGM studios or 20th Century Fox – a portion of the painting would be painted black to complement an area that was actually blackened out on the set, so you’re getting two parts of a puzzle that are double exposed together and you don’t really need to use a sheet of glass in every instance to do a composite shot, glass comes in handy for other types of effects.

KH: So let’s talk about some of the movies you’ve worked on, we don’t have the time to do them all so let’s do some of the big ones. I have seen on various profiles that your first movie was Close Encounters as an assistant matte artist?

RG: Yes, as an assistant, and to clarify what an assistant does is a throwback to the olden days of being a squire in knighthood or an arrow makers apprentice or an assistant blacksmith. Much of what you are doing is helping out the artist in the most basic chores that go with doing an oil painting, in other words the beginner in a department like that, might just do some pencil tracings to help lay out piece of artwork, and one of the many chores that you had to do as an assistant matte painter in the days of painting with paint brushes was take the big stacks of dirty paint brushes that the main artist, in my case it was Matt Yuricich who was mentoring me; you’d clean their paint brushes for them, you’d scrape the paint off the dirty paint palette and push a broom, you know, clean up after them. But you would do understudy type work while you were learning how to produce a matte painting. So it’s the same, it’s the same kind of a thing, you know, prior to the use of all the modern, you know, not-so-dirty equipment like computers these days, but in the old days it was messy business and the painting with oil paints requires that you make sure the artist is always supplied with good, clean paint brushes and simple things like that. So on Close Encounters, although I already knew and what got me my job was, I did have some animation to show and a portfolio full of artwork. I was being trained as a matte artist and the actual matte painting that I got to do on the show amounted to some painting elements, runway lights turning on, a lot of scenes where the city gets blacked out, you know the electric goes out and you see all the city lights getting sequentially knocked out or sometimes just coming back on when the power grid is turned back on, but I probably only did three complete matte paintings for Close Encounters of the Third Kind. What was fun was just working in and around all the different artists. Douglas Trumbull, who was the head of that visual effects department and his partner Richard Yuricich you was Matthew’s younger brother, but was the cinematographer, he was the main man for the camera department and did the camera work on that show, which included initially Close Encounters, but later on that same crew they worked together on Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Blade Runner. But those guys, they allowed us to do some crossover work, so I might be helping out on some of the elements shooting of the saucers and the tank cloud or sometimes spending time with Greg Jein in his model building department but we were allowed to do a little bit of crossover work on that show, and I got to be around all that was going on that show, I’m rambling here, but on that show it was not uncommon either; Steven Spielberg would walk into the effects department without an entourage of people around him, he’d just come in on his own and sit and watch dailies when they would project them and make notes and chat with the crew and it was a much smaller set up. At most, on average, we wouldn’t have any more than 30 to 35 in the entire effects department on Close Encounters of the Third Kind, each in their own training and disciplines that they specialized in, whether it was optical compositing or matte panel work or miniature construction, motion control photography.

KH: That must have been a bit of a treat, to meet Mr Spielberg?

RG: You know, the previous film he had done just prior to Close Encounters, a year or so before was Jaws. So I think Steven Spielberg was just around 30 years old I think, or in his early thirties at most when he directed Close Encounters of the Third Kind and was just a very fun, vivacious, colourful personality – loved to talk about motion pictures with anybody and you could see he was just inventing new shots, he was always ready to sit down and scribble something up that he wanted to see. He was really a fun and energetic director. And, you know, as years go by, I don’t think he’s lost much of that, I think that when I see his films that have come out over the years, he always to me, whatever type of film he chooses to do, it always feels like he’s ready to get out on a limb and take a chance now and then, which is more than can say for a lot of the directors that, you know, have come along over the years, you’ll see them stagnate or not try new things and Spielberg, I think, I try to keep an eye on whatever he does and once in a while I’ll go the theatre and see of this films. Actually I’m very pleased with how he takes chances.

KH: Your paths crossed again when you worked on Hook?

RG: That was before too much digital was involved. There was about fifty percent of the compositing work, or nearly fifty percent, there were more opticals than they expected I think, they were trying to do mostly digital compositing on Hook. We were still doing traditional matte painting work on that show, but I didn’t get to see Steven even once on Hook, I was working at ILM. The main supervisor was a gentleman I had worked with years prior, Eric Brevig , was the visual effects supervisor, who spoke more one on one with Steven Spielberg and screened dailies with him separately from the effects crew. I think they worked back and forth between Los Angeles and San Francisco, but I stayed where we were doing the matte painting, that was the only time I worked at Industrial Light & Magic. My friend and fellow matte painter Mark Sullivan, called me up, he was heading their department at that time and said Rocco, do you want to come up here and work on Hook? So that was the only job I did at ILM, but I didn’t get to see Spielberg on that show.

KH: You mentioned Star Trek before. You’ve had the distinction of working on both of Star Trek’s cinematic births with The Motion Picture and J.J. Abrams Reboot?

RG: Yeah, that actually makes me smile, it was one of those things where I did very much enjoy doing matte painting work for Douglas Trumbull, along with my mentor Matthew Yuricich who did much of the matte painting work on Star Trek: The Motion Picture, but by that time, a couple years after I’d worked with him on Close Encounters, we were each at our own easel creating matte paintings for Star Trek: The Motion Picture; a project that was done in a tremendous hurry, because Douglas Trumbull had initially passed up the opportunity to do the work on that movie, he had other projects in the works, some of his Showscan projects and so forth that he was developing so he decided not to take on the effects work that he was offered to do on Star Trek: The Motion Picture and some months had gone by and the show was being done by Robert Abel & Associates, they’d taken on the job and things weren’t going well, Paramount was not happy with the pace with which the work was being created and they got worried about it. So the work was then pulled from Robert Abel & Associates and reassigned it to two companies, Douglas Trumbull and Apogee out in the valley, that was John Dykstra’s company, they did most of the Klingon work. Then that many years later in 2007, you have the J.J. Abrams Star Trek. But that work, because it was just a huge amount of digital work, I didn’t get to work with J.J. Abrams on that show.

KH: You were obviously part of a team for the Abrams Star Trek?

RG: My company on the J.J. Abrams Star Trek, actually what Douglas Trumbull’s job, you know, on the Robert Wise Star Trek, probably didn’t work with the director either, there was just so much work to do and we were just kept very busy as part of Doug Trumbull’s crew, so any of the discussion that occurred with Robert Wise was typically either done with Richard Yuricich and Douglas Trumbull in contact with Robert Wise on that show but Doug’s crew were just full time, very busy with the miniature work and the matte painting work and compositing on Star Trek: The Motion Picture, but then that many years later, what is it thirty years between those shows, my company – I had partnered up with a friend at the time and we were working on the J.J. Abrams movie and our company Svengali, was the name of it, with myself and a young producer who was dealing with the producing end of the effects – we took on about 70 shots for the J.J. Abrams Star Trek, and I was one of about a handful of matte painting artists that we had, and we had a lot of compositing work that we turned around for that show to, but there were many teams of effects companies on the J.J. Abrams first Star Trek movie – and I think that movie came out very nicely. I was real pleased with the work on that.

KH: So, more often than not, in your line of work you report more to the head of the effects department and not the director?

RG: Up until the time, before digital effects existed, I would work very commonly, one on one, I would meet with the director and producer of the movie. But, when it was matte painting work just done on film – what happens, and can explain this a little more clearly to, any of the screen credits you see for me; other than the iconic ones that you’re talking about like – although on Blade Runner I did get to talk with Ridley Scott, he would come and visit Douglas Trumbull’s Entertainment Effects Group, and he would sit in dailies with us and discuss what he wanted on the matte paintings there, so he would pop in. Ridley Scott is a tremendous sketch artist along with the guy he hired Syd Mead. But Ridley is definitely capable of picking up a pencil and paper and doing a very good drawing and conveying what he wanted – but, what I was going to say is, by the time I worked on Star Trek: The Motion Picture myself and five other Doug Trumbull employees decided to form our own company called Dream Quest. I headed that matte department and from that time on until my very first digital matte painting work which came around 1997, I did work directly with the film directors on most of the screen credits that you can find my name on. On Gremlins I’d meet and work with Joe Dante on that, you know so, many of the other shows we did, actually our little company Dream Quest which grew pretty rapidly, we would meet with not only the visual effects supervisor on those shows, but the directors would know us on a first name basis, you might have read about Dream Quest back in the day, I don’t know?

KH: Yeah I did. So you’ve had the privilege of meeting some of the big hitters?

RG: Yeah, I mean John Badham who directed many of the shows we had at Dream Quest including Blue Thunder and Short Circuit; he was a repeat customer at our Dream Quest company. I left Dream Quest and actually just wanted to start my own little matte painting department apart from them in 1986, myself and my matte painting buddy Mark Sullivan split off and started a little matte department/effects shop that didn’t have any specific company name, we were just going under our own individual names and at that point in time I did work on Robocop and worked for Paul Verhoeven, which was his first American film. So anything you would see screen credit wise from 1986 on, I’d pretty much be called in, most of those shows didn’t have more than a handful or a dozen or so matte painting shots, I like those kind of movies better because more often than not, there not just wall to wall visual effects, they’re little movies, sometimes they’re westerns, sometimes they’re simpler science fiction movies – Robocop didn’t have more than seven matte paintings I don’t think – but they’re important ones. But back from the Dream Quest days and since you mentioned J.J. Abrams, he a couple of years ago, purchased one of my old matte paintings that I got to do; it was something at Dream Quest that is almost iconic and it was only a movie that had three matte paintings in it, but the first movie Vacation with Chevy Chase, when he drags his family on a cross country chase through Europe…

KH: Oh, National Lampoon’s?

RG: Yeah National Lampoon’s Vacation. But the Walley World amusement park is completely a fabrication – they came up with it to make fun of the theme parks and Disneyland – and that director, who was a wonderful guy to work for, I worked with him on Caddyshack prior to Vacation, but Harold Ramis who passed away a couple of years ago, was a very fun director to work for and a few years back, one of my matte paintings of Walley World for Vacation was purchased by J.J. Abrams, so he’s got that on his office wall now.

KH: Well that must make you feel good, that they have life after their initial use?

RG: Yeah, yeah – a rebirth or an interest that people have, in collecting some of the old oil paintings.

KH: Well I think it’s an incredible art form, and watching a lot of behind-the-scenes programs that I love to do, seeing the old way it was done, together with the skill involved, trying to match something that has to be composited along with a live action element…

RG: Yeah, what fun. You know as far back as I can remember even as just a youngster, doing that kind of work, you didn’t feel the magic, you know, you felt, and what’s interesting in its earliest and most basic form, you’d be working on a sheet of glass, right out there on location in front of the camera, and painting a castle that you know, you could see through the view finder on the location camera and someone would come over and say what’s going on here, and they’d look through the view finder and it’s like looking at a magic trick, because it’s all happening right there, through the lens. There’s just something about it, and it’s not there quite, anymore. The new methods are great, they’re a good way to go – but some of those old methods, which are still viable by the way, that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be used, it’s just what they take is a certain amount of planning and commitment to a look and one of the things that exist these days more than ever is the exact opposite of that, there’s a tremendous amount of indecision.

KH: It really was an art form that was incredible because you have to match, when you talk about that kind of work, the lighting and the existing background elements. You can’t just go up there and paint something that is situated correctly – it has to comp well with the background, to give the illusion at least, that it’s there?

RG: For a paint brush artist it’s a challenge and it was a very fun and good challenge and there were relatively few artists that could do it, in those earlier days. The quantity of matte painters that were traditional paint brush matte painters, that I was working with, if you were to total up all the good matte painters of the 80’s there weren’t more than twenty people, that could do that art form and do it well – so we were specialists and, you know, going back into the golden age of Hollywood, each studio had a department of probably no more than a half dozen or ten artists in each department for each of the major studios. And sometimes they’d switch over. I know Matt Yuricich, my mentor, worked at 20th Century Fox until the mid-1950’s and then switched over to MGM for the rest of his career at a major studio and then he free-lanced after MGM closed its matte painting department. But that studio would still call him from time to time even though they didn’t have a full-time matte department they still had the equipment and some of the personnel, so he might get called in to work on a movie now and then. But, you know, it did end up going away from the studios are more into the freelance effects companies. What was I going to say, Oh, you probably are going to work your way around to asking about some of the other shows, or did I get to work with any of the directors, some of the first time directors would include Kevin Costner on Dances with Wolves.

KH: I was just about to ask you about Dances with Wolves, what was that like?

RG: Yeah westerns are indeed a lot of fun because what’s being asked of you, and around that same time, a very good Australian director of photography , Dean Semler, of Mad Max and Road Warrior fame, he was hired by Kevin Costner to shoot Dances with Wolves and almost the same, within a year of that, I worked on another western, although it was a modern-day western called City Slickers with Billy Crystal which was also shot by Dean Semler – so you get to see some of the same crew from one show to the next. I did like westerns because what you get to do its always so suspect, not like a science fiction movie where you’re doing a futuristic cityscape, everyone’s going to say wow, look at that nifty futuristic cityscape, where in a western really, what they wonder is, how the hell did they get that many buffalo out there on that location, instead on thinking that you are looking at some sort of trick…

KH: That it could be a matte painting?

RG: Yeah, fun stuff. Also years later I got to work on a Mel Gibson movie called Apocalypto, and Dean Semler, he was the director of photography on that show. That film has some wonderful visual effects.

KH: And they’re the kinds of films that most wouldn’t expect matte paintings in. The naturalistic setting presents the notion that a great deal of matte work would not be required, as opposed to fantasy films where it is commonly expected?

RG: it’s true, and part of that is, when they go to a location like that, which has gorgeous vistas and sunsets, this is going in the opposite direction and are shows that didn’t work on but when I saw Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies I was just blown away of course by gorgeous landscapes that are down in New Zealand, the mountains and skies and so forth, which really served as a perfect integration for the trick shots and the matte paintings that they did. Though people have seen those landscapes before, to enhance them and combine them with trick shots works very well, but I noticed in the more recent movies they’ve gone completely digital and have done away with shooting on location for the Hobbit movies for instance, and they don’t look nearly as impressive as something shot out in the wide open spaces.

KH: So you’re saying something that combines effects shots and natural vistas, you find more effective?

RG: It’s what makes a matte shot work, in my opinion. Because if you are looking at a really beautiful set or really good back lot with some nice lighting or a really good location, if there are people standing outside under sunlight, just something enough to guide your eye and make you see that you are looking at something real, then what you’re doing when you blend and match the lighting on a matte painting and put the correct perspective match on everything it gives an illusion, but because you’re looking at a combination of things, you know, and you see that live action portion that’s real, it fools you, it makes you think this must be real, we’re matching to something that’s real. When you start doing the entire thing, and you’ve only got a green stage and an actor sitting on a green apple box, you’re setting yourself up potentially for something that won’t look as real, unless you really have a good plan. It takes a lot more effort, to go out and shoot under real sunlight to have at least half of the scene actually done.

KH: Sure, and that must have been something you encountered when working on a film like Cliffhanger?

RG: Oh Yeah. The more you’ve got, even if you’re doing a shot completely from scratch, it’s what you’re intercutting with, the stark reality, it forces your hand, it forces you to have to match something to looks completely real. Where if what you doing looks like a stage, a very stagey effect, than the best you can do, if you want to maintain continuity is maybe, you know, match the look that’s on the set, but more or less you’re going to be trapped into matching the look of whatever it was that you’re intercutting with. So if you’re on a really good-looking location or a set then at least, you know, part of that, it sets, it sets a look that you’ve got to maintain.

KH: On a film like Cliffhanger, what type of work did you do on that, are you simply trying to match vistas that had to be extended or hide cable rigs?

RG: Well actually the matte artist, and I’m going to give the credit to her, she was my boss. When I went off to do my Dream Quest company, Matthew Yuricich, on Blade Runner, hired a new apprentice, her name is Michelle Moen, and she ended up working with him for many years and when Douglas Trumbull’s company switched out of that facility, it became, and was taken over by Richard Edlund, Boss film – Matthew was still in the department for a number of years on Ghostbusters, on Die Hard etc., and Michelle was there with him doing matte painting work and by the time Cliffhanger happened, Matthew had retired from the department and Michelle Moen was in charge on Cliffhanger and so she called me up and had me come in and work as an additional matte painter on that show. But most of those matte paintings on Cliffhanger were her work, and, I was going to say, of the crew, they had one of the guys who had been at ILM because that’s where Richard Edlund came from before he started Boss film, he brought some people with him and among them Neil Krepela, who had shot a lot of really extensive high resolution transparencies of the mount ranges that they were using on location with Stallone. All the real beautiful live action photography, Michelle Moen matched her mountains to. The two shots I got to work on were the same thing, we were matching to something that was very real, though, what it was, they couldn’t really, constantly be putting Sylvester Stallone in peril, so much of those trick shots that are in that movie are relatively invisible. They have him, supported by wires, and often you’ll see a stage or a rig that would be hidden later on by a matte painting. There’s a big pull back that Michelle did where Stallone’s on the face of a cliff and the camera moves backwards, for a long time, between cliff walls that were built in miniature and he ends up being just a tiny little speck.

KH: Yes, I know the shot. But, another film in your filmography that I wish to talk about, because it’s one of my favourites, is Buckaroo Banzai?

RG: Oh my God, what fun. Yeah, in fact, the director on that was W.D. Richter and a visual effects supervisor is an old friend whom I know from Douglas Trumbull’s place is Mike Fink, and he, he split the work up between my company, Dream Quest, and Peter Kuran’s company VCE, Visual Concepts Engineering. But Dream Quest, our group did much of the crazy looking flying, they look like sea shells almost, the spaceships in that show, and there was a lot of fun, and the crazy sky background shot that we created for the flying ships that were done with cotton clouds are similar to the ones in the movie Brazil, you know, but we actually had a stage filled with fibre-filled cotton that was all sculpted out by myself and the other matte artists and some of the model crew. And then we did a continuation cloudy sky background painting, but there are a number of other matte painting shots in that show. But yeah, Buckaroo Banzai, gosh we had a lot of fun miniature work in that show, and it’s a very entertaining movie. I got to meet Peter Weller and then again on Robocop we got to chat, and I got to know him better then, afterword.

KH: I’ve seen among your credits you’ve done some visual effects work as well as your matte painting work, is that correct?

RG: Yeah, it’s true, although I’m known primarily for matte painting work, I like to think of myself as a good visual effects creator, and that includes animation, compositing work – I tended, especially in the pre-digital day, but even nowadays too, I tend to want to do my own compositing, and anytime there’s any enhancements and animation to be done, anything that brings the shot to life.

KH: Another film I wanted to ask you about, another favourite of mine that not many people remember, is D.A.R.Y.L.?

RG: Oh yeah, we shot live action, for the shots we did in and around Orlando, Florida and there’s some very nifty model work to that our company did, Dream Quest did, with a miniature of a blackbird jet an SR-71 that gets blown up. There’s also some matte paintings and some sky background tricks, and it’s a good movie – but not your typical science fiction film.

KH: True, and I’ve not see anything like it since.

RG: If you look, it might have been on a Facebook page that I have, there’s a shot that didn’t end up getting into D.A.R.Y.L. that we did for the movie and I just have basically a still photo of one of the background paintings we did, where you’re looking down from about 30,000 feet. It was a lot of fun, it’s just myself hanging on a rope high above the clouds, it’s a real wow of a still photo. It really shows off the artwork, I used to use it to impress people because it looks like I’m a stunt person in one of those cliff-hanger moments.

KH: When I was looking through your credits, I noticed a lot of films. You’ve worked on shows like Tremors 2, Little Nicky, Apocalypto (as you’ve mentioned), First Knight, the Sean Connery King Arthur movie…

RG: Oh that was just one quick redo shot we did for that. You know I think I still have a matte painting, that was a revision matte painting that was done for Rob Roy, which was what I thought was a wonderful movie with Liam Neeson. That was a fine movie. But, what was I going to say – when I mentioned John Badham, who directed Blue Thunder and Short Circuit, there’s a bicycling movie he did with Kevin Costner called American Flyers, the same director, John Badham, did Saturday Night Fever back in the day and a bunch of films in the 80’s, but he would keep coming back to our little company in Culver City and say hey, can we put a sunrise in behind this bridge or he would just come up with ideas. It was fun back then with the traditional effects work. Sometimes you’d get repeat customers. Actually Danny DeVito, I worked on his first directing job, a little TV movie called The Ratings Game which I think has just come out on blu ray. Again, you meet these first time directors and they would come back to you and ask you from one show to the next, hey, I’ve got an idea, can we try this? But back before visual effects were all the rage like it is nowadays, you certainly would just come up with ideas and say gee, I wonder if we could make this happen.

KH: So, as we wind up here, do you have any favourites among the films you’ve worked on?

RG: Well certainly the ones that the sci-fi and effects fans love are pretty good stand-outs, like Blade Runner and Robocop, Gremlins, of course I mentioned National Lampoon’s Vacation. I think most folks back then had no idea they were looking at matte painting work, they probably thought they found – well they did go inside the Magic Mountain amusement park, and used their rollercoaster at the end, but the entrance to that park and the big moose head themed sign and stuff – I don’t think anybody expected that those were trick shots. I loved working on Close Encounters because it was the first show that I worked on. I was only 18 years old and four months out of high school when I was working on that. I don’t know if I’ve mentioned it, but I’d sent some work through the mail and I had been a teenager in Ohio, which is a few thousand miles away from Los Angeles and got hired over the phone to work on Close Encounters.

KH: Like you’ve said, Blade Runner is still, though it was made in what they refer to as the analogue era of effects, a beautiful movie. Analogue or digital I don’t care, it is astounding.

RG: That’s right. If it’s well done it doesn’t matter what method they used. The thing with Blade Runner, the proof is, they went back and did clean-up work and got rid of little mistakes here and there, but for the most part the visual effects could be left alone in that movie – they are that perfect.

KH: It has also been your privilege to work with the big names in visual effects like Matt Yuricich, Richard Edlund and certainly Doug Trumbull.

RG: Thanks, the real kick, if you get to interview him, he never changes. The guys got a tremendous memory, he’s got a good scientific mind, but he’s got a great sense of humour, never have I worked with a man that made me laugh as hard as Doug Trumbull, he’s a character.

But thank you for calling me and wanting to do an interview.

KH: It’s been wonderful, because really admire the work you used to do, and I don’t mean that derogatorily.

RG: (laughter) No I appreciate it, and I agree when you said, liking the older work, because to me what works about a lot of those older scenes and a lot of those older shots is that they are just good basic compositions. The camera isn’t flying all over the place like you’re looking at a video game, you know, it’s just straight forward filmmaking and it works by virtue of its simplicity.

KH: Your back now working in your own company?

RG: Well on and off. I’ve got my own company, after thirty used I moved my shop from West Los Angeles, about ten miles south of where I was before. But I do work for other companies as a freelance artist, in fact these last couple of years I’ve been working as a digital matte painting artist on Game of Thrones.

KH: So do you have any big films that are coming up?

RG: Well I really don’t. There is that feature I mentioned coming out later this year called La La Land, where they had me do one panoramic shot, which goes by in about nine seconds, a sweep across Paris at night. So it’s a Parisian cityscape which the camera passes over it quickly, before ending when it passes through the entrance of a jazz club at night, which they did with a miniature. But that shot was all done with old fashioned/traditional trickery on film, the whole film was shot in 35mm, so the director wanted to see a slightly more stylized looking Paris at night for those shots. It almost at the end of the movie and that will be coming out later this year. But as far as anything that’s going on right now, I’m in-between projects.

KH: Well thank you sir, it has been a privilege to talk with an artist of your calibre and experience..

RG: I’m an old timer, just one of those old timers…

KH: You’ve worked on a lot of films that are dear to my heart and I thank you.

RG: Thank you, thank you. You take care, and we’ll be in touch.

That was Rocco Gioffre dear readers, a master artist, of the cinematic persuasion.

(Coming soon: The stuff that dreams are made of: Remembering Explorers with Eric Luke by Kent Hill)

Matte paintings featured:

This interview is best watched or listened to. Just too long to read.

LikeLike