I have always been a lover of film music. Having come from a very musical family, I was surrounded by everything from Stravinsky to story books on records. Yet I have fond memories of my Grandmother buying this record that had a compilation of science fiction movie music. It had music from Star Wars, Star Trek, 2001 . . . just to name a few.

Of course I have always been obsessed with movies. And my Grandmother would continue buying me music from the films I would talk with her about – that’s until I admit; I started to get particular about the whole business. If I came out of the theatre humming themes from the movie, chances are I was on my way to buy the score.

Much to my chagrin I have not done that in a while. Probably the last time was when I picked up Giacchino’s score for the new Trek movie in 2009 – but, in the years leading up to that I bought a lot of film music. One such score I went straight from the theatre to the music store was Superman Returns. My relationship with that film I have already written about on this site. ( if you so desire you can read it here: https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/2016/08/31/a-nice-day-for-supermans-return-by-kent-hill/ )

The composer was John Ottman. A phenomenal talent who came up in the industry working with Bryan Singer on all of his films as composer but also as editor. A unique part to play in the film business, though when you read further, you’ll find he regards the dual role as quite a nightmarish undertaking.

It was fascinating talking with John as we covered his early days, adventures in the X-Men trade, a little of Superman’s return, passions projects, future possibilities. It was a rare treat to finally to chat with a film composer – but as you’ll discover, John Ottman, is so much more . . .

KH: John was working in films always your dream?

JO: Yeah, ever since I was a kid I was making movies in my parent’s garage, and invariably convert them into some sort of space station or spaceship, you know, and get my neighbours and my friends to act in the movies, so I started as far back as grade school.

KH: You are primarily known as a composer. Was it a case of: I want to work in movies so what can I bring to the table? Was it a love of music and film scores that set you off down this path?

JO: Well actually the music is something that, you know, is like, you fall into what you least expect to be doing. I was a film music fan, and on my movies I would take the scores Williams and Goldsmith and Horner – I took great pleasure in putting their names up on the screen when I was doing the credit sequences of my films. But anyway, so I basically, I played the clarinet and I knew music and I listened to film scores, I sort of got trained, my sensibilities watching the original Star Trek actually, cause they would reuse a lot of the same scores and it gave it sort of a cohesion in terms of themes and so forth, but to cut a long story short, you know, I was doing the first feature with Bryan Singer and our composer dropped out in the eleventh hour and we had a Sundance deadline, and I had been doing the composing as a hobby ever since MIDI technology came along in the 80’s, I was writing pieces in my spare time and scoring my friend’s student films and short projects and so forth, so his back was against the wall, and I knew the character more intimately than anyone cause I had created him in the editing room and knew what made him tick, and so anyway I wrote the score and we won the Sundance film festival and after that we put The Usual Suspects together – that’s when the blackmail began basically, because I was like well, I like writing film scores, screw this editing thing, and Bryan says, Oh hell no, you’re not ever going to write a score for me unless you’re the editor so (laughter) that is sorta how it all began. It’s like my agent says: “Does Danny Elfman have to wash Tim Burton’s car to get to score his movies? So that started the collaboration with Bryan as a filmmaking partner.

KH: So this was Public Access, the first collaboration?

JO: Right, correct. So I fell in love with writing film music and, you know, film scoring you can be in and out of a movie from a matter of weeks to couple of months, three months sometimes four months, but you’re going to be able to keep things fresh and go on to something different or even have a break, you know, so the long haul of making a movie can be two years, so I go to what’s called editing jail and I leave my scoring career for a long time, and then of course the process of managing an entire film basically what I do and scoring it, and it was easier when I was younger but, I don’t recommend it.

KH: When I saw that you both score and edit, do you function in the dual capacity or to you cut the film and then score it or are you thinking about the score before you have footage to cut?

JO: I only think about the score to the extent is, I worry about having to write it someday. How I am going to do it, I have no idea because the editing of course and the management of the movie never stops, so I’m always tormented by when am I going to be able to write this thing, cause it’s not like I say one day to everybody, hey, I’m gonna go write the score now, let’s just stop making the movie. But no I actually – people are surprised to know that I cut dry, I don’t cut to any music whatsoever, because I feel like if I’m cutting sequences and put music in right away, even if it’s a temp track, I feel like that’s a crutch. There is no time for me to write original music for me to temp the film with cause we have to show the film to the studio to get approved so I do have to put temporary music in when we present the first cut of movie – as I am putting the movie together I don’t put in any music at all. I feel like, if you put music in to sell, every editor wants to sell a sequence, so everyone’s like, great, loved the sequence so then we present another sequence. The problem with that, I find, is that the music fools everyone into thinking the scene is working better than it is, and it just delays any potential problems that are going to inevitably happen later, and I’d rather face those problems upfront cause I don’t have time to have a film that’s a problem child cause I got a score to write, it’s gotta work, so what I do is I put the movie together with no music or maybe there might be one scene with some music on it, and I feel like if I’m sitting back and watching it and I don’t want to blow my brains out and it’s working, then the score is just going to bring it to another level, but it’s not dependent on the score to tell the story. So, after the whole film is put together in my editor’s cut, then I will put the temporary music in, and it’s almost better to do it that way to, because over the process of making the movie, it constantly is changing and if you put music in as you’re cutting going to get hacked up and hacked up and hacked up, it’s not going to have any like, cohesion to it. So that’s what I do, I put the music in after it’s all put together in the first cut of the film and then we present it, and that gives the studio of course, an idea of the kind of score that’s going to be written and then, as you know, the mayhem and hell on Earth never stops, the film is always in flux and, somehow, I tell everyone we’re screwed if I don’t start writing soon (laughter), then it’s the sorta thing where I go home, I write for two or three hours and then I race back to Fox, or wherever we’re making the movie, to deal with a test screening or meetings or ADR with the actors or dealing with visual effects problems and so on.

KH: Bryan Singer and you have been together since his debut, you must; by now have a great short-hand with each other?

JO: Yeah, it’s all about trust I think. He feels, I imagine, less trepidation because we have a track record. He’s sort of a reactor. He likes to react to something. If it feels him feel good or it gives him chills or it makes him feel involved in a scene, then he reacts. So he kinda trusts me to determine what the sound of the movie is going to be then he will, dig it or not.

KH: So he has no preconceptions? He just waits for you to present it and then he gives the thumbs up or down as it were?

JO: That’s exactly right. He’s afraid if he tells me to do something that it might destroy some potentially great idea I might have had, so he doesn’t want to ruin something I might be thinking or – he doesn’t want to rain on my parade I think until he hears it, but then if he hates it he can rain on my parade. But I think both editorially and musically there’s a trust factor like I said, so he can relax and know that things are being taken care of.

KH: He can focus on bringing it altogether and you picking up the slack as it were?

JO: He can focus on having a life, like a lot of director’s have…

KH: While you’re locked away labouring over it hey?

JO: (Laughter) I destroy my life to enable his.

KH: Everything for the director’s vision?

JO: Yes, (laughter) yes. But I think we’ve sort of created each other’s sensibilities over the years, in terms of the taste factor. I think if I’m writing something or I put a scene together or come up with some interesting way of conceiving the scene editorially, if I’m getting chills or I’m getting excited about it, there’s a good bet he’s going to feel the same way. But if he doesn’t I’ll just scream at him. (laughter)

KH: Well you have of late being to a lot of superhero stuff with Bryan with regard to the X-Men movies. Are you yourself a fan?

JO: Well I never read a comic book in my life before doing X-Men. I just treat it as another movie and I learn, of course with X-Men, because it’s based upon the lore of the comics and so forth I do my research and then became sort of an aficionado simply by the very fact I wanted to learn about these characters and what made them tick, and X-Men I guess had some added meaning for me because, you know, being a gay guy, you know, and X-Men is all about the misfits and being misunderstood or unaccepted and whether your gay, your black, your fat, this is I guess what the lore is about is being accepted or not accepted. So I though X-Men 2 was very ballsy in that regard because it had that coming out scene with Bobby who is the snowman or ice boy or whatever he’s called (laughter) in his living room with his parents, and I was like wow, this is really blatant.

KH: Hey Bobby, have you tried not being a mutant?

JO: That’s right, exactly. But you know what’s interesting about the scene is if you key into what it’s about and you understand X-Men, you totally get that scene almost like you’re being hit over the head, but if you’re like – I think those people who really don’t understand all of this, I think it went right over their heads, (laughter) but think that’s sort of the genius of that scene. But of course that got me connected to it; of course it was my big orchestral score and superhero films allow someone like me who’s a thematic composer to just let my hair down with the orchestra and write emotional themes and so forth. So it was my first outing in that regard and there was a lot of excitement connected to that film and it was also just a good experience that movie, unlike most film experiences, I don’t remember there being a lot of (laughter) horrible things that happened on that movie.

KH: Well X-Men 2 is still today, even with the great influx of superhero cinema, regarded as one of the better comic book films?

JO: Yeah, I think it’s the best X-Men film. I mean Days of Future Past, people are saying that’s the best one, but obviously the most recent thing people always think is the best, and I’m very proud of Days of Future Past but still, my heart is in X-Men 2 as being the best one because it just had this sort of like . . . emotion to it, you know, we got some of that in Days of Future Past as well and we really endeavoured to do that because of X-Men 2, to give it the same resonance at the end and so forth, but yeah, there’s just something great about X-Men 2 and the characters and the story.

KH: That is one of my favourites among your scores; that rousing, almost John Williams-like march at the opening of the credits?

JO: Thanks. I was happy to resurrect it for the last couple of X-Men movies, cause it went away a couple of times.

KH: I have ask a question I’ve always wanted to ask someone like yourself who was connected to the production – the ending of X-Men 2 has a kind of Wrath of Khan feel to it, was that conscious?

JO: (laughter) A little bit. I mean, Wrath of Khan, Bryan and I would always sort of say was the bible, you know, that movie is just a great movie in terms of character development and story and of course the score, and so it’s almost like instead of asking what would Jesus do, you ask what would Wrath of Khan do? So I think I was very much thinking about, you know, how emotional the end of Wrath of Khan is and so I wove some of that in there. I don’t know if it was conscious to be a rip off, but I think the feeling and the influence of that score, well, it was an influence that’s for sure.

KH: I thought it was fitting, and I know a lot of people homage elements of other films, but think it was executed well so when you come to the ending, as in Wrath of Khan and we hear Spock do the voice over for the first time instead of Kirk, and then in X2 we hear Jean instead of Professor X?

JO: Right, right, and I thinks that’s obviously why my brain inevitably had to go there, but the irony to is, Jean Grey’s theme, I think very unintentionally but strangely has cord comparisons to a few cords in the Wrath of Khan wrap-up, so I think the planets align where the person who’s a real, real aficionado of the Star Trek 2 score hears the influence, but I don’t think just anyone would notice the couple of cords that are there in a similar pattern.

KH: While we are on the subject of superheroes, I wrote a piece about Superman Returns which you worked on. What was that experience like; getting to incorporate Johnny Williams’ themes into your score, which I might add, I think you did beautifully?

JO: Well before I actually began the movie, I felt I was getting death threats practically on the internet, people would complain that John Williams isn’t scoring it, and who’s this guy, why is Ottman scoring it? I felt sort of like, oh my god, I feel so unworthy (laughter) writing this score and I’m going to make nobody happy, so it was a really daunting task. Then one day I finally just said, I’m just going to forget about all of that, otherwise I’ll be crippled by the whole thing, so I’m just going to write the score the way I would normally approach a film, and all of my sensibilities and my concepts of writing scores were learned from Williams and Goldsmith and those masters anyway, so I kinda fall into the same kind of approach that they would take, accept it’s my own my own you know, so I just went on to score the movie, and I scored it like I would any other movie except I would just incorporate a DEN-DA-DAH!, every so often (laughter). But I did harken a couple of times, you know, one time I harkened to Lois Lane’s theme, and obviously the opening is John Williams’ theme. But then I wrote some themes of my own like Lex Luthor never had a theme and I wrote one for him, so I guess by some miracle it was really embraced by even the most insidious haters, so I felt like I had a victory, and I did, I really killed myself on that score, it’s probably I think 115 minutes or 120 minutes of music I wrote, and I guess what gets irritating from time to time is the whole: well it was just John Williams’ music, but, you know, yeah, but if you really count the number of Williams’ nods in that score it’s probably a few minutes. So I wrote a shitload of music and we recorded it at the old Todd AO theatre in Studio City, which doesn’t exist anymore, which is a really large scoring theatre with great sonic qualities to it.

KH: Well I think you did a great job on that score and I think it was a grand idea to use it in the first place, rather than with the recent Man of Steel and its creation of a whole new musical voice for Superman. What attracted me initially to Superman Returns was the fact it was peppered with nostalgia.

JO: Yeah, it’s both a strength and a weakness of the movie – I’m not talking about the score, you know the movie came out at a time where it’s on the heels of one of the greatest movies ever made, the 1978 version of Superman, and so it’s like, I think the fear if we veer too far and suddenly made it like some Man of Steel thing, it would have been universally rejected, but at the same time, it was crippled in a way by being so reverential to the original, which of course makes me emotional and people who like the 78 version. But it felt like it sort of restricted the movie in a way. You know, I am very proud of it, it’s definitely a flawed film, but I think artistically it’s also a beautiful movie, so I am very proud of that.

KH: It was my perception that the movie came together really quickly. I know there were other directors attached – but then it seemed like rapid fire, okay we’re finally making this Superman movie now?

JO: My memory is kinda sketchy, but, you know, we were supposed to do X-Men 3, so I was all excited to do that because I had laid down all these seeds in the X-Men 2 score to expand upon all those in X-Men 3 and then Bryan called one day and said we’re doing Superman. I was like WHAT!

KH: I remember reading somewhere that the director of the eventual X-Men Last Stand was attached to Superman, then there was this shift and he and Bryan swapped movies?

JO: I don’t remember that, but yeah, I was in Australia for six months so it wasn’t, the shoot wasn’t that accelerated, and I remember we didn’t really, you know how these tent pole movies go, it’s crazy but they often go into these – they start shooting films with scripts that aren’t fully ready. I remember one of the things that wasn’t fully realized or realized at all was the whole Metropolis, what I call Metropolis mayhem, which was shooting through the streets and saving all these people, we didn’t have any sequence for that so we were heavily in post and then we were like shit, we don’t have anything – so I had to fly back to Australia and we storyboarded some things and I am still in disbelief how fast the visual effects people were able to make any of that work cause it was literally done at the last second, all that stuff, that whole sequence. If you look at it it’s not perfect visual effects wise cause it’s so rushed, but I look at it and I’m in awe how fast they were able to do that, I mean there were dead bodies on the floor and vodka bottles rolling around in the hallway, but they got it to work.

KH: And did you like the country while you were down this way?

JO: I miss Sydney big time, because when you’re working somewhere, you really don’t get to enjoy were you’re at, when you’re an editor and composer – I mean other people can enjoy their lives more. But yeah, every time we go shoot somewhere I feel as though I have unfinished business and I want to go back to that place and enjoy it, so I do want to go back to Sydney.

KH: So you’ve worked with Bryan a lot, but you’ve also worked with some other notables like Shane Black a couple of times on Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang and The Nice Guys – what’s Shane like?

JO: He’s a really nice guy; let’s just say he’s a character (laughter). But he also, you know I guess a lot of directors are that way – they want react to an idea you have. Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang is one of my favourite scores only because it wasn’t really temped with anything that worked and so I sort of, you know, I took the film home and tried to figure out what can I do to this movie to give it some sort of quirkiness or interesting personality, and I felt what if I do like a retro 60’s kinda score, cause it’s not a period piece, it’s a current day movie, and that’s what gave it this kitschy kinda quality, it’s really just me fucking around on the keyboard, with really some bongos and stuff, and I suddenly had this epiphany and then I brought out like an electric piano and sort of came up with this funky theme, and I sent to Joel Silver, the mock-up of it, and he kept playing it in his car over and over again and he goes I LOVE IT! I LOVE IT! I LOVE IT! So I have to say I think my score for that helped really define that movie, so the challenge of The Nice Guys was that well, this time it is a period piece so, you know, if you put the 70’s kitschy music on a 70’s movie, it is really easy to fall into parody and make the film feel like – like your making fun of the movie as opposed to being in with the film. So think that was the biggest challenge with The Nice Guys score, and it was really hard to ride that line. Unfortunately with The Nice Guys there wasn’t a title sequence animated for my score, so there was really no time to introduce the main theme, therefore I just played the main theme ad nauseam whenever I could stuff it into the film because it was a buddy-buddy film and I wanted the main theme to represent the two of them.

KH: It’s good to see Shane making resurgence. He was initially revered as a writer, what’s he like to work with as a director?

JO: I only dealt with him very little on Nice Guys and Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang just by happenstance and I ended up working with Joel a lot. I mean, Joel is sort of a control freak and is very, very involved. Let’s just say he’s a hands-on producer. That I respect about him a lot, and frankly Joel comes from the old school of film scoring, so he’s actually very sophisticated about film music, and he’s very – so is Shane – so the two of them they’re both very concerned that making sure the score has melody and is thematic and that comes from the influence of, you know, the older films they like so in that regard I enjoy working for both of them.

KH: While we’re on the subject of directors, have there been any other collaborations that have been great experiences?

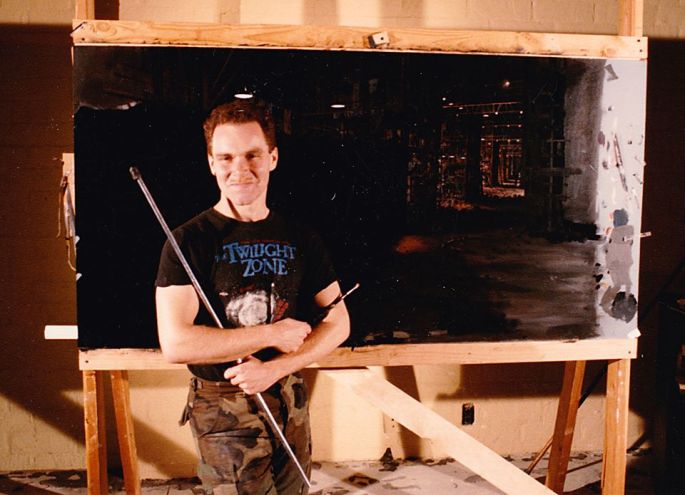

JO: Yeah, I mean, my favourite scores or experiences have been from the films that bombed or that nobody saw, I mean, Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang is actually one of those, no one saw it in theatres, it’s a great movie and so it caught on and became a little cult classic, so that’s one that bombed that actually people know now. There are others like Astro Boy, which was my foray into animation, which was one of the best experiences of my career, and I did this really emotional, positive, feel-good, joyful score which I don’t normally get to write, you know, the London symphony, it was like a love fest, you know, people in animation, I think, seem to be happier and more well-adjusted people. So the director and I got and great and the producers, I think it was the only time in my career where, I couldn’t wait for them to come over and listen to the next batch of cues. Normally you dread when they come over. Yeah I went to London, his parents met my parents and we recorded the score, people were crying and then the film made 3 million dollars, (laughter) and it’s like, it’s just like really devastating, it was devastating for me but really devastating for him, cause he must of spent over at least a couple of years of his life on the film. So you know, that’s what happens, that’s part of filmmaking. And I did a film way back with John Badham called Incognito, and it remained as such because it was never released, and I think it’s my most masterful work because, it was this movie where – it was all about art forgery, and there were these long extended sequences, some 4 and 5 minutes long with no sound design, no dialogue, it was an all musically driven movie, so it was like being commissioned to write a classical score. It was about a guy forging a Rembrandt, Jason Patrick was the star – I think their whole marketing campaign was to market Jason Patrick on the success of Speed 2…

KH: Oh No…

JO: …Yeah and when Speed 2 tanked and no one liked that movie, they had no way to market Incognito, so they just threw it in the can. So Incognito, it’s not a masterful film but it’s a really great story; Peter Weller had started directing it and then John Badham took over – and that was a great experience for me but again, really, really depressing because the score was just something composers would die to do and no one saw it.

KH: You’ve enjoyed a host of varied experiences, from the big summer movies, but also you’ve worked on films like The Cable Guy; you’ve done a Halloween movie in H2O, Lake Placid, Eight-Legged Freaks . . .

JO: Yeah, I think the best thing for anyone in this business is when they can jump to different genres because people always say: “what genre do you like?” – I say well, whatever I haven’t been working in for a while, because it just inspires you to go into something different. Earlier in my career with Suspects, I was pigeonholed as the sinister guy, so even though Suspects isn’t really sinister, after that I was doing a lot of darker films. Then I got into little quirky films and I discovered I had this real knack, this natural knack for quirky movie scores so, they did this Fantasy Island reboot, the ill-fated series, and I did things like Pumpkin and even Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang or even a movie like Eight-Legged Freaks, it’s quirky, that’s for sure.

KH: Do you have a preference though, when you look for the next film, is there a genre you go for above others?

JO: No, no I really don’t. I wouldn’t be good at some kind of rap score or super modern thing, that wouldn’t be my thing. . .

KH: So you’re not secretly a Bernard Herman looking for the next Hitchcock movie?

JO: No, no, no. I would love to do, I mean, like I said for instance with the Astro Boy thing, you know, that was a very positive, emotional, joyful kinda score and that, I jumped at the chance because I just get to don’t often get to do those kinds of things, I mean it was a superhero film technically, so I guess I was still in the superhero genre. It was like the Fantastic Four films too, they were not great movies, but they offered me a chance to do lighter superhero fare, where X-Men is decidedly darker and rides that psychological line more carefully because it’s so serious where Fantastic Four films, I got to have a little more fun in terms of letting the music be a little more pop corny or whatever.

KH: I want to ask, you are commonly known as Bryan Singer’s composer like Williams is to Spielberg. Is that or has that been a help or a hindrance in your career?

JO: I do think it’s a hindrance, I mean, I think, you know, for better or for worse, cause you know Bryan makes me do the fricken editing thing, but I think it’s good for a composer when you have a star director you’re connected to you cause I think it helps your stock as a composer, so in that regard I can’t say, I’d say it’s a positive to be connected to a big director, I really can’t see it as a negative being associated as that director’s composer.

KH: No, I wasn’t insinuating that, I mean it in the sense that when you’re not doing work for Bryan and they ask for you not as John Ottman but merely as Bryan Singer’s guy?

JO: That’s why it’s important for me, when I’m finished on one of these X-Men films, I’m so destroyed, like I was talking to you offline about how my personal life is such a cataclysmic cataclysm that I don’t want to work, I want to take a break after these movies, but what I should be doing, you know, is jumping at scoring some of these other films for other directors, which I do want to do for sure, but I just have to recharge my batteries, but by the time my batteries get recharged he’s got another fricken movie (laughter). So I go back to editing jail and then the syndrome continues.

KH: Well you are doing double duty and not solely focusing on the score?

JO: Well that’s then thing, it’s not like I just go in and score the film like my peers that are just scoring films, and I’m like ALL YOU HAVE TO WORRY ABOUT IS SCORING A MOVIE! (laughter), I have to worry about all these other things. I am at a point in my life where I have these filmmaking needs, you know, and one of them, if there is any silver lining at all to managing a film with Bryan or editing a film for Bryan is I get to flex my filmmaking muscles, and sometimes when I’m just scoring films for a while, I miss, I used to miss being a little higher on the totem pole. You know film composers used to be the luminary person who would walk in and the angels would sing and the seas would part – but now you walk in and it’s basically like you’re craft service because it’s a different world now with computers and producers see their son’s friend composing shit in their garage with garage band or whatever, so I think the art form of film music has been devalued and let’s face it, a lot of film scores now, it’s basically ostinatos and waws – so there’s a lot of junk out there which I think devalues the art form. But what I was going to say, when I have time off, I want to branch out into other things to; I think TV is like the new medium now for being able to delve to characters and story development and so forth aka Game of Thrones and so forth – so I watch that stuff and I’m like wow, I’d love to be involved, not as a composer, but as a director, I’d love to direct some TV pilot, not pilot, episodes, but sure I’d love to direct a pilot. But yeah, that’s something I’d love to get into just to break it up you know.

KH: A pause from the perils of tent pole filmmaking?

JO: Yeah, but of course I’d love to score some smaller movies to, get back to my roots, some of those independent and quirky films – but also, I started as a filmmaker and I directed that feature, Urban Legends, and it was what it was which is like a silly teen horror movie but, there are facets of that I’m proud of, I loved working with the actors and it was very exciting so, I miss that. There’s too many fucking options is my problem. If I could split myself into three different people, you know, one to go off and do one thing and one to go off and do another (laughter). Once I make a decision to do one thing I screw myself out of doing another – but of course that’s life you know.

KH: I must be nice to be in that position to have such options – even though it’s tiring – it must be nice to be in demand?

JO: Yeah, it’s really tough to say no to things. I’ve been offered a couple of things as editor, and it’s like, I don’t want to go do that to myself, but it’s like people who are much respected in the business asking me, and painfully I just so no, it’s so hard to say no when want you – but I’m not going to edit a film right now are you crazy. The worst punishment you can put a human being through is to go edit a movie (laughter).

KH: I noticed your name connected with a new 20,000 Leagues under the Sea. Can you tell us anything about that?

JO: Well it’s in development; it’s not even in preproduction right now as far as I know, they’re doing some early day’s concepts, pre-vising and things like that, I really don’t frankly know any more than that. Places like IMDB always jump the gun on these things, then your mother calls you and goes, “Oh, you’re doing this movie?” and I’m like, “I am, I don’t know?” (laughter)

KH: I know it’s a project that’s been kicking around for a while, so I was just curious.

JO: I’m just trying to enjoy my free time right now, so I’m trying not to think about it. You know, the thing with the three monkeys, one’s got his hands over his eyes . . .

KH: Hear no evil, see no evil, and speak no evil?

JO: Yes, yes.

KH: Well John, I’m not going to take up any more of your time, but it’s been a privilege talking with you. I am a great admirer of your work.

JO: Thank you, well you have good taste.

KH: I hope to hear more, see more or even see you get to direct another one. Perhaps get someone else to edit and score so you can kick back?

JO: I feel very sorry for that person (laughter). I’ll probably end up doing all three myself again – but like you said, it’s good to have options.

KH: Again you’ve been very generous with your time, John thanks again mate.

JO: it’s been great talking with you.

Well that was John Ottman ladies and gentlemen, a man of music and as well as many other talents; and like I said to the man himself, I look forward to witnessing more of his incredible work. In fact I’ve got Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang right here on my desk – might, since I’ve done with this interview, kick back and reward myself with beer and a movie…

(COMING SOON: VIRTUALLY SPEAKING: AN INTERVIEW WITH BRETT LEONARD BY KENT HILL)