When The Bourne Identity (2002) debuted in theaters, audiences were hungry for a new kind of spy film. The James Bond movies adhered to a tried and true formula and it had gotten old. Mission: Impossible II (2000) collapsed under John Woo’s stylistic excesses and a boring love story with no chemistry between Tom Cruise and his love interest played by Thandie Newton. The world had changed dramatically since the events of 9/11 and a new international espionage action thriller would have to acknowledge this new reality. Along came The Bourne Identity, a very loose adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s novel of the same name and it connected with audiences even if most critics hated it.

A mysterious, unconscious body is found floating out at sea by a boatload of fishermen. Two bullets in his back and a device that stores a Swiss bank account are found embedded in his hip. He wakes up with amnesia and one of the men onboard fixes him up. It isn’t until almost five minutes in that the first bit of understandable dialogue is uttered. Up to that point director Doug Liman drops us into this strange world without any set up so that we are disoriented, much like the film’s protagonist and therefore we identify and empathize with him almost instantly. These first few scenes establish the film’s style – constantly moving camerawork often with jarring, jerky movements that mimic our hero’s disorientation.

After two weeks at sea, he makes his way to land and begins a quest to uncover his identity. Over time, he discovers skills he didn’t know he had but that come out instinctively, like the ability to disable two armed police officers with his bare hands in Switzerland. He checks out his Swiss bank account and discovers that his name is Jason Bourne (Matt Damon). The safety deposit box contains money, passports for several different countries, and a gun. It becomes obvious that Bourne assembled this stash of supplies in case of a situation like the one he’s currently experiencing.

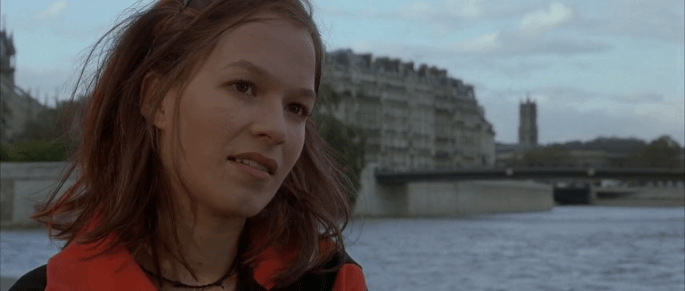

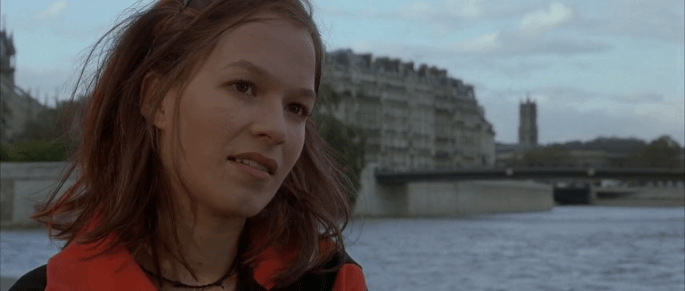

After a daring escape from the United States embassy, Bourne pays a young German woman named Marie (Franka Potente) to drive him to Paris where he apparently lives. It turns out that he’s some kind of lethal, CIA-trained assassin who has something to do with a top-secret operation known as Treadstone and he should be dead. It seems that the United States government is trying to silence an exiled Nigerian dictator by the name of Nykwana Wombosi (Adewale Akinnuoye-Aghaje) now living in Paris. He wants the CIA to put him back in power in six months or he’ll blow the whistle on their attempt to assassinate him. The man in charge of Treadstone – Alexander Conklin (Chris Cooper) – wants to make sure Bourne is dead because he was supposed to kill Wombosi when something went wrong. He sends three other assassins after Bourne and Marie.

Because Bourne suffers from amnesia and is being hunted by a secret branch of the CIA, we sympathize with his plight. It doesn’t hurt that he’s portrayed by Matt Damon who comes across as instantly likable and empathetic. Before The Bourne Identity, he was not regarded as an action star and so his capacity for sudden bursts of ruthlessly efficient violence and the ability to escape from several dangerous situations was a revelation. Damon pulls it off and more importantly is convincing as a deadly assassin with no memory. He is nothing short of a revelation as Bourne and the actor does an excellent job of not only gaining our sympathy early on, but also maintaining it throughout as we root for Bourne to figure out who he is.

When Bourne breaks out his martial arts for the first time in the film we are as surprised as he is and not just because it’s the first time we’ve seen him do so, but at the time Damon had never done a film like this before and it was his debut as a man of action. To his credit, he looks very adept and comfortable in the fight scenes and doing the stunts. The first substantial fight sequence where Bourne is attacked by a fellow Treadstone assassin is a visceral set piece as he uses everyday objects like a pen to defend himself. This is not the clean, polished style of Bond movies, but down and dirty fighting that looks bloody and painful. It has a personal vibe to it as the fight takes place up close and personal in an apartment. I like that the film shows Marie’s reaction to what has just happened. She is genuinely shocked and upset at the sudden outburst of violence she witnessed. As she and Bourne flee the scene she even throws up as a reaction to being in real danger.

The casting of Franka Potente as Bourne’s love interest is an intriguing choice. She doesn’t have the supermodel looks associated with the Bond girls. She’s beautiful with a nice smile and an easy-going charm. She’s relatable and grounded – part of the film’s realistic aesthetic. Marie is an everyday person thrust into extraordinary circumstances once she encounters Bourne. Potente also brings a certain amount of international cinema cache thanks to her breakout performance in Run Lola Run (1998). As a result, she doesn’t come across as some damsel in distress, but a proactive foil for Bourne. They quickly develop an easy rapport as he finds her constant, nervous talking comforting. Damon and Potente play well off each other in these early scenes as her character humanizes Bourne so that he’s not just some inhuman killing machine.

Chris Cooper is ideally cast as the no-nonsense bureaucrat Conklin who knows more than Bourne and yet is always one step behind in finding and catching the elusive assassin. He isn’t given much to do, but makes the most of his limited screen-time as he orchestrates the search for Bourne with considerable technological resources at his disposal. Cooper exudes just the right amount of uptight malevolence that we’ve come to expect from a Republican-controlled government. A young Clive Owen shows up as a Treadstone assassin who methodically tracks and then kills his targets. His showdown with Bourne in a field of tall grass is a tension-filled sequence as our hero uses misdirection to get the drop on the assassin, neutralizing him, but not before he imparts crucial information about Bourne’s past.

One of the reasons that The Bourne Identity was such a game changer for the spy movie genre came as a result of taking the hi-tech surveillance used in movies like Enemy of the State (1998) and updated it on a global scale as Conklin and his room full of I.T. specialists (including character actor extraordinaire Walton Goggins in a small role) track Bourne’s movements in Europe. Everyone leaves electronic footprints be it through credit card use or being picked up on security cameras and this was even more prevalent after 9/11. This heightened sense of surveillance has become a part of our daily lives. There is a certain delicious irony at work as Liman crosscuts between Conklin and his staff using sophisticated technology to find two people who are doing their best to stay off the grid, which results in them taking refuge in a house in the French countryside.

I like that Liman shows Bourne and Marie actually trying figure out his identity by doing the legwork involved as they call potential leads on the phone, visit key locations and talk to people as they try to put together the jigsaw puzzle that is his past. There’s a nice sequence where Bourne walks Marie through a task that he needs her to do for him. As she makes her way through a hotel lobby his words play through her head and we hear them over the soundtrack in voiceover narration.

At the time of its release, much was made of the chaotic production that pitted indie director Doug Liman and against Universal Pictures. Their dirty laundry was aired in the mainstream press and there was speculation that The Bourne Identity was going to be a box office failure. After the critical and commercial success of Go (1999), Liman decided to pursue his passion project – an adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity, a book he loved while growing up. It had been published in 1980 and featured an ex-foreign-service officer on the CIA’s hit list. Liman read it again while making Swingers (1996) and found that the characters still engaged him. He inquired about the film rights and found that Warner Bros. controlled them. Over time, the rights expired and Liman met Ludlum at his home in Montana, securing the rights. In 2000, Liman asked screenwriter Tony Gilroy if he would rewrite the screenplay he had for The Bourne Identity. After the success of The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Gilroy had gotten a reputation for saving damaged scripts.

At the time of its release, much was made of the chaotic production that pitted indie director Doug Liman and against Universal Pictures. Their dirty laundry was aired in the mainstream press and there was speculation that The Bourne Identity was going to be a box office failure. After the critical and commercial success of Go (1999), Liman decided to pursue his passion project – an adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity, a book he loved while growing up. It had been published in 1980 and featured an ex-foreign-service officer on the CIA’s hit list. Liman read it again while making Swingers (1996) and found that the characters still engaged him. He inquired about the film rights and found that Warner Bros. controlled them. Over time, the rights expired and Liman met Ludlum at his home in Montana, securing the rights. In 2000, Liman asked screenwriter Tony Gilroy if he would rewrite the screenplay he had for The Bourne Identity. After the success of The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Gilroy had gotten a reputation for saving damaged scripts.

Gilroy was not thrilled with the source material: “Those works were never meant to be filmed. They weren’t about human behavior. They were about running to airports.” Liman persuaded Gilroy to read the script, which he realized was “awful,” but they met and the latter asked the former why he wanted to make this film. Gilroy declined Liman’s offer, but when pressed gave him a suggestion: toss the novel and keep the idea of an assassin with amnesia. “You only have one way to find out … What do I know how to do? I guess your movie should be about a guy who finds the only thing he knows how to do is kill people.”

Liman eventually wore Gilroy down and he agreed to work on the script. While the first five minutes of the film comes from Ludlum’s book everything after Bourne gets off the boat was created by Gilroy. At the time, Matt Damon wanted to “try an action movie … exactly the way I’d love to do it, with someone who was thinking outside the box. Doug being Doug, this would be an interesting movie.” He agreed to do the film after meeting Liman and reading Gilroy’s script.

Liman took the project to Universal Pictures in the first place because “it was just as important to them as it was to me to make this a character-driven movie and not just a generic action movie.” By his own admission, the director was mistrustful of studio decisions like their suggestion that he shoot in Montreal instead of Paris to keep costs down. He argued that the Canadian city didn’t look like the City of Lights and the studio relented. Liman applied his often chaotic, unpredictable style of filmmaking to a big budget studio film with mixed results, often angering the producers. For example, once in Paris, he hired a crew that didn’t speak English (so he could practice his French).

When Damon arrived he didn’t like the changes made to the script after the one that made him sign on in the first place. Liman had brought in David Self (Thirteen Days) to fix what he felt was a problematic third act when Gilroy left to write Proof of Life (2000). Some of the character-driven material had been removed in favor of bigger action sequences. According to Damon, Self “went to the book and did a page-one rewrite. Every few pages, something blew up … It was not the movie I agreed to do.” Editor Saar Klein remembers, “We went into production with a script that was just a mess.” Liman agreed and Gilroy came back after finishing Proof of Life to write new scenes and fax them from New York City to Paris.

Producer Richard Gladstein left the production because his wife was going through a difficult pregnancy. Universal did not want Liman filming unsupervised in Europe and brought in veteran producer Frank Marshall who had known the director since he was a child. The studio felt that Liman’s approach was unorganized and unnecessarily costly. He responded by saying, “I like to keep my options open. I’m known for changing my mind.” The studio also felt that he lacked maturity. For example, one night Liman paid the crew overtime to light a forest for him to play paintball. Liman claimed that the studio hated him and they tried to shut him down: “The producers were the bad guys.”

It got so bad between Liman and the studio that they rejected anything he said. The director ended up using Damon as his surrogate, but this only worked for a short time. One day, Liman realized he’d missed a shot and asked the producers if he could redo the scene. They said no and so he loaded four minutes of film in a camera and reshot the scene himself, which infuriated the producers. This resulted in a giant screaming match on the set. At one point, Liman even toyed with auctioning off his director’s credit on eBay. Despite all the friction between Liman and the studio the end result speaks for itself. The Bourne Identity was a commercial hit, but the studio had not surprisingly soured on Liman and banned him from directing the sequels. “I lost my baby,” he said.

The Bourne Identity was shown to a test audience who liked it, but wanted more action at the end. After much debate with the studio, Liman and Gilroy devised a new action sequence. The screenwriter did not enjoy the experience of working with Liman finding that the director “didn’t have any sense of story, or cause and effect.” Liman found Gilroy “arrogant” and at one point attempted to hire a new screenwriter until Damon threatened to quit if his script wasn’t used. Gilroy saw a rough cut during post-production and was worried that the film wasn’t going to be good. It had come out a year late and went through four rounds of reshoots. He tried to take his credit off the film and arbitrated against himself. He wanted to share credit (and blame) with someone else. After all the dust had settled the film went over budget by $8 million and two weeks over schedule. This forced Universal to move the original release date of September 2001 to February 2002 only to push it back again to May 31 and finally settling on June 14.

What separates The Bourne Identity from the Bond films at the time is that it took the international espionage thriller and personalized it. For the most part, the adventures that Bond had in his movies never affected him personally (the notable exception being License to Kill and now the Daniel Craig films) while in The Bourne Identity it is very personal, but without sacrificing all the things we’ve come to expect from a spy movie: exotic locales, exciting car chases, lethal bad guys, and intense fight scenes. What made the film such a breath of fresh air was how it tweaked these tried and true conventions.

At its heart, The Bourne Identity is a mystery as Bourne tries to figure out who he is and why there are people trying to kill him. This gives Liman the opportunity to ratchet up the tension as Bourne is constantly looking over his shoulder, never able to rest for too long and unable to trust anyone except for Marie. Known previously for character-driven independent films Swingers and Go, Liman showed his adeptness at working in multiple genres by bringing his trademark loose, almost improvisational approach that breathed new life into the spy genre. It had become safe and predictable and it took an outsider like Liman and casting against type with Damon to shake things up. Without The Bourne Identity, Casino Royale (2006) would have been a very different film and the subsequent Daniel Craig Bond films wouldn’t be as gritty and substantial as they are.

At its heart, The Bourne Identity is a mystery as Bourne tries to figure out who he is and why there are people trying to kill him. This gives Liman the opportunity to ratchet up the tension as Bourne is constantly looking over his shoulder, never able to rest for too long and unable to trust anyone except for Marie. Known previously for character-driven independent films Swingers and Go, Liman showed his adeptness at working in multiple genres by bringing his trademark loose, almost improvisational approach that breathed new life into the spy genre. It had become safe and predictable and it took an outsider like Liman and casting against type with Damon to shake things up. Without The Bourne Identity, Casino Royale (2006) would have been a very different film and the subsequent Daniel Craig Bond films wouldn’t be as gritty and substantial as they are.

After the film’s dismal reception, no other adaptations were completed. It took actor Johnny Depp and his friendship with Thompson to get any kind of serious attempt at an adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas even considered. In the end, I think that the problems I have with Where the Buffalo Roam are best summed up in a speech Thompson gives at the end of the film where he says, “it just never got weird enough for me.” Amen, my brother.

After the film’s dismal reception, no other adaptations were completed. It took actor Johnny Depp and his friendship with Thompson to get any kind of serious attempt at an adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas even considered. In the end, I think that the problems I have with Where the Buffalo Roam are best summed up in a speech Thompson gives at the end of the film where he says, “it just never got weird enough for me.” Amen, my brother.

Like with the other Bourne films, Ultimatum also has exciting chases, including the police pursuing Bourne over rooftops in Tangiers while he’s chasing an assassin going after Nicky, and a crazy car chase through the busy streets of New York City. Greengrass and his stunt people upped the ante on the chases, most notably the sequence in Tangiers, which starts off with scooters in the busy streets and then after a car bomb goes off, along rooftops on foot. Greengrass’ kinetic camerawork is taken to the next level as we literally follow Bourne leaping through the air from one building to another.

Like with the other Bourne films, Ultimatum also has exciting chases, including the police pursuing Bourne over rooftops in Tangiers while he’s chasing an assassin going after Nicky, and a crazy car chase through the busy streets of New York City. Greengrass and his stunt people upped the ante on the chases, most notably the sequence in Tangiers, which starts off with scooters in the busy streets and then after a car bomb goes off, along rooftops on foot. Greengrass’ kinetic camerawork is taken to the next level as we literally follow Bourne leaping through the air from one building to another. If Identity was about our hero escaping from his CIA handlers and Supremacy was about him figuring out why they are still after him, then Ultimatum is all about getting revenge on those responsible for messing up his life in the first place and figuring out, once and for all, his identity. What elevates Ultimatum (and the rest of the series) above, say, the Mission: Impossible movies, is that it is more than just an exciting thriller (although, it does work on that level). It is also has a sharp, political component in the form of a scathing critique of the CIA’s dirty little secrets. The series ultimately asks, what happens when a highly-trained and conditioned government operative questions what he does and why? How does he undo the programming that made him what he is and come to grips with what he’s done? This film answers these questions to a satisfying degree while also being very entertaining conclusion to the series.

If Identity was about our hero escaping from his CIA handlers and Supremacy was about him figuring out why they are still after him, then Ultimatum is all about getting revenge on those responsible for messing up his life in the first place and figuring out, once and for all, his identity. What elevates Ultimatum (and the rest of the series) above, say, the Mission: Impossible movies, is that it is more than just an exciting thriller (although, it does work on that level). It is also has a sharp, political component in the form of a scathing critique of the CIA’s dirty little secrets. The series ultimately asks, what happens when a highly-trained and conditioned government operative questions what he does and why? How does he undo the programming that made him what he is and come to grips with what he’s done? This film answers these questions to a satisfying degree while also being very entertaining conclusion to the series.

Joan Allen’s Pamela Landy is an interesting character in that initially it appears as if she will be an antagonist like Conklin in The Bourne Identity, but when she’s assigned to investigate the Berlin job she uncovers the existence of Treadstone and this brings her up against Ward Abbott (Brian Cox), the operation’s caretaker and the man who also mothballed it. She’s no dummy and quickly figures out its nature, what Conklin was up to and Bourne’s role, which, in a nicely executed scene, quickly recaps the events of Identity for those who haven’t seen it. Over the course of Supremacy, she shows indications of sympathy towards Bourne’s plight that are developed further in The Bourne Ultimatum (2007). Allen’s scenes with Cox are interesting as they are often fused with tension as Landy uncovers the secrets of Treadstone while Abbott, clearly uncomfortable with his dirty laundry being aired, tries to cover his ass, which makes for some heated exchanges between the two as they butt heads.

Joan Allen’s Pamela Landy is an interesting character in that initially it appears as if she will be an antagonist like Conklin in The Bourne Identity, but when she’s assigned to investigate the Berlin job she uncovers the existence of Treadstone and this brings her up against Ward Abbott (Brian Cox), the operation’s caretaker and the man who also mothballed it. She’s no dummy and quickly figures out its nature, what Conklin was up to and Bourne’s role, which, in a nicely executed scene, quickly recaps the events of Identity for those who haven’t seen it. Over the course of Supremacy, she shows indications of sympathy towards Bourne’s plight that are developed further in The Bourne Ultimatum (2007). Allen’s scenes with Cox are interesting as they are often fused with tension as Landy uncovers the secrets of Treadstone while Abbott, clearly uncomfortable with his dirty laundry being aired, tries to cover his ass, which makes for some heated exchanges between the two as they butt heads. The people behind the Bourne franchise are smart and willing to take chances. They cast an atypical action hero with Matt Damon, surrounded him with an eclectic cast that mixed Hollywood and internationally known stars (with the likes of Julia Stiles, Brian Cox and Karl Urban) and hired independent filmmakers like Doug Liman and Paul Greengrass against type to direct, letting them put their own unique stamp on their respective films. Ultimately, The Bourne Supremacy is all about the title character making amends for his past. There is a scene where he confronts the woman, whose parents he killed, that is rich in understated emotion as Bourne takes responsibility for his actions and tells her what really happened. It’s a great way to end the film as Greengrass eschews the cliché of a climactic action sequence (which happens before this scene) in favor of a more poignant one as Bourne atones for one of his many sins while also setting things up for the next installment.

The people behind the Bourne franchise are smart and willing to take chances. They cast an atypical action hero with Matt Damon, surrounded him with an eclectic cast that mixed Hollywood and internationally known stars (with the likes of Julia Stiles, Brian Cox and Karl Urban) and hired independent filmmakers like Doug Liman and Paul Greengrass against type to direct, letting them put their own unique stamp on their respective films. Ultimately, The Bourne Supremacy is all about the title character making amends for his past. There is a scene where he confronts the woman, whose parents he killed, that is rich in understated emotion as Bourne takes responsibility for his actions and tells her what really happened. It’s a great way to end the film as Greengrass eschews the cliché of a climactic action sequence (which happens before this scene) in favor of a more poignant one as Bourne atones for one of his many sins while also setting things up for the next installment.

At the time of its release, much was made of the chaotic production that pitted indie director Doug Liman and against Universal Pictures. Their dirty laundry was aired in the mainstream press and there was speculation that The Bourne Identity was going to be a box office failure. After the critical and commercial success of Go (1999), Liman decided to pursue his passion project – an adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity, a book he loved while growing up. It had been published in 1980 and featured an ex-foreign-service officer on the CIA’s hit list. Liman read it again while making Swingers (1996) and found that the characters still engaged him. He inquired about the film rights and found that Warner Bros. controlled them. Over time, the rights expired and Liman met Ludlum at his home in Montana, securing the rights. In 2000, Liman asked screenwriter Tony Gilroy if he would rewrite the screenplay he had for The Bourne Identity. After the success of The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Gilroy had gotten a reputation for saving damaged scripts.

At the time of its release, much was made of the chaotic production that pitted indie director Doug Liman and against Universal Pictures. Their dirty laundry was aired in the mainstream press and there was speculation that The Bourne Identity was going to be a box office failure. After the critical and commercial success of Go (1999), Liman decided to pursue his passion project – an adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity, a book he loved while growing up. It had been published in 1980 and featured an ex-foreign-service officer on the CIA’s hit list. Liman read it again while making Swingers (1996) and found that the characters still engaged him. He inquired about the film rights and found that Warner Bros. controlled them. Over time, the rights expired and Liman met Ludlum at his home in Montana, securing the rights. In 2000, Liman asked screenwriter Tony Gilroy if he would rewrite the screenplay he had for The Bourne Identity. After the success of The Devil’s Advocate (1997), Gilroy had gotten a reputation for saving damaged scripts. At its heart, The Bourne Identity is a mystery as Bourne tries to figure out who he is and why there are people trying to kill him. This gives Liman the opportunity to ratchet up the tension as Bourne is constantly looking over his shoulder, never able to rest for too long and unable to trust anyone except for Marie. Known previously for character-driven independent films Swingers and Go, Liman showed his adeptness at working in multiple genres by bringing his trademark loose, almost improvisational approach that breathed new life into the spy genre. It had become safe and predictable and it took an outsider like Liman and casting against type with Damon to shake things up. Without The Bourne Identity, Casino Royale (2006) would have been a very different film and the subsequent Daniel Craig Bond films wouldn’t be as gritty and substantial as they are.

At its heart, The Bourne Identity is a mystery as Bourne tries to figure out who he is and why there are people trying to kill him. This gives Liman the opportunity to ratchet up the tension as Bourne is constantly looking over his shoulder, never able to rest for too long and unable to trust anyone except for Marie. Known previously for character-driven independent films Swingers and Go, Liman showed his adeptness at working in multiple genres by bringing his trademark loose, almost improvisational approach that breathed new life into the spy genre. It had become safe and predictable and it took an outsider like Liman and casting against type with Damon to shake things up. Without The Bourne Identity, Casino Royale (2006) would have been a very different film and the subsequent Daniel Craig Bond films wouldn’t be as gritty and substantial as they are.

Machete not only features all kinds of wild action sequences but also has something on its mind, commenting on the rampant immigration problems that continue to plague the states along the United States/Mexico border. Along the way, Rodriguez plays up and makes fun of Latino stereotypes (they are all day laborers and love tricked out cars) only to twist them into a rallying cry, a call for revolution that takes full bloom by the film’s exciting conclusion in a way that has to be seen to be believed. Best of all, Rodriguez has created yet another awesome Latino action hero. Forget Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables (2010), Machete is the real deal and a no-holds-barred love letter to ‘80s action films. As great as it was to see many of the beloved action stars from the ‘80s and 1990s, I felt that Stallone’s film never went far enough. Rodriguez’s film doesn’t have that problem as it gleefully goes all the way with its cartoonish violence.

Machete not only features all kinds of wild action sequences but also has something on its mind, commenting on the rampant immigration problems that continue to plague the states along the United States/Mexico border. Along the way, Rodriguez plays up and makes fun of Latino stereotypes (they are all day laborers and love tricked out cars) only to twist them into a rallying cry, a call for revolution that takes full bloom by the film’s exciting conclusion in a way that has to be seen to be believed. Best of all, Rodriguez has created yet another awesome Latino action hero. Forget Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables (2010), Machete is the real deal and a no-holds-barred love letter to ‘80s action films. As great as it was to see many of the beloved action stars from the ‘80s and 1990s, I felt that Stallone’s film never went far enough. Rodriguez’s film doesn’t have that problem as it gleefully goes all the way with its cartoonish violence.

The Fellowship of the Ring is one of those rare films that lives up to its mountains of hype. Jackson tells an engaging story and crams as much of the source material as possible into the film. Sure, certain characters and subplots have been cut-out but that is the nature of a feature film adaptation. Maybe, someday, someone can turn it into a mini-series so that everything can be included. Until then, we have Jackson’s magnificent films to enjoy.

The Fellowship of the Ring is one of those rare films that lives up to its mountains of hype. Jackson tells an engaging story and crams as much of the source material as possible into the film. Sure, certain characters and subplots have been cut-out but that is the nature of a feature film adaptation. Maybe, someday, someone can turn it into a mini-series so that everything can be included. Until then, we have Jackson’s magnificent films to enjoy.