Few could have predicted the ‘broadcast yourself’ era, and fewer realize it was predicted by a no-budget indie smash film that cruised across pop culture like a steamroller before most people had personal phones, much less YouTube accounts. Back in 1999 The Blair Witch Project was sold to audiences with a desperate selfie video of an aspiring documentary filmmaker who was about to die a horrible death, apologizing for her actions and begging forgiveness. It was gripping stuff that launched a thousand copycats—a whole genre unto itself of microbudget ‘found footage’ frights—and never really had any true challengers to its first jolt to the zeitgeist. Fast forward your camcorder to 2016, where indie cinema of the nineties has given way to studio tentpoles and remakes, wherein we of course get a return to Burkittsville (sorry, only one way tickets) helmed by the talented filmmaking duo of Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett. Responsible for the successful indie thrillers You’re Next and The Guest, not to mention a sneaky brilliant anti-marketing campaign that harkened back to the clever promotion of the original, thus raising expectations (the film was publicly titled The Woods until a San Diego Comic Con reveal earlier this year), the pair have lovingly crafted Blair Witch as a direct sequel to the 17 year old horror classic. Unfortunately love and talent don’t trump genuine creativity, and the new film embodies most criticisms you’ll hear these days about slavish fan service and the attempts to create a franchise out of every successful movie ever made.

Not to say we get poor effort here. Wingard and Barrett know thrills, pacing and how to entertain, and they definitely know their source material. Gushing in fandom during a live Q&A session after the screening, they discussed everything from the deep mythology to their clever Easter Eggs sprinkled throughout (keep an eye open for a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo from the original camera itself, supposedly one of the most expensive props on the production), so believe me when I say there truly is a lot of love up on the screen throughout Blair Witch. We’re introduced to a larger group of players led by the kid brother of Heather, the first filmmaker to fall victim in the Maryland woods. Despite huge search parties, no remains or house were ever found after the last collection of footage went viral, so James (James Allen McCune) harbors hope that his sister is still out there, and as luck would have it his new friend/love interest Lisa (Callie Hernandez) is an aspiring documentary director! Together they will assemble friends and bravely repeat every mistake the other doomed crew made, and then some. Modern technology enables all filmmakers involved to capture multiple angles in a much richer fashion than the single camera of The Blair Witch Project, and thanks to years of self obsessed iPhone footage littering the internet the audience doesn’t even stop to throw out the loudest criticism of the genre—why would anyone still be filming this as the situation goes to hell? In 2016, of course they would.

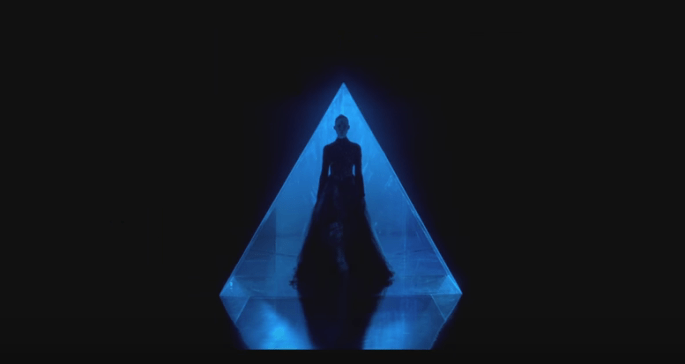

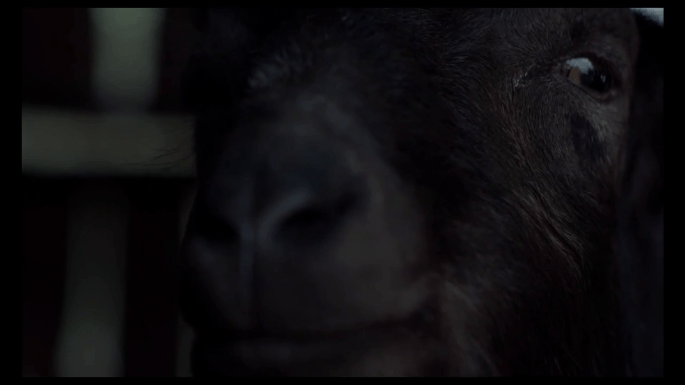

Sadly all of these ingredients don’t add up to the original magic. A small group of non-actors allowed to improvise almost every scene in the first film is now replaced by a large ensemble of professionals clearly following a script. Additions of digital quality sound jolts and lighting end up subtracting from the immersive experience that cast a spell on audiences back in the day. And in trying to amp up the third act, Wingard and Barret commit an unforgivable sin that undermines every suggestive horrific joy we all loved the first time around—they show us the monster. Amp up that third act they do, but instead of achieving thrills with new terrors, they simply continue to ape the exact three act structure of The Blair Witch Project, which is ultimately Blair Witch’s downfall. Figuring out a creative way to get a different group of people fiddling with their smartphones into peril and not slavishly repeating most of the beats that were much fresher in The Blair Witch Project would have served the movie well, but safe choices are made through the film, leaving the viewer stewing in a musty brew of nostalgia and disappointment.