Films like Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind come around once in a lifetime, if we’re lucky. I watched it when I was too young to fully grasp much, and it flew over my head. In the last few years I had a revisit and was knocked flat. Few stories out there have the power to mine deep within the human psyche and search for the complexities, contradictions and puzzling flaws that lie in the beautiful disasters we call human beings. A contemplative yet fast paced meditation on relationships, love, heartbreak and reconciliation doesn’t even begin to paint a picture of what you’re in for with this uniquely told and one in a million film. Sagely ragamuffin Michel Gondry, not one for the easy way out, has truly outdone himself, as has screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, who is never short on wild ideas with emotional heft that sneaks up and blindsides you. Joel Barrish (Jim Carrey) ditches work on a whim one morning, and hops a train out to snowy Montauk. Through fate’s mysterious grasp, he meets free spirited Clementine (Kate Winslet), and the two hit it off immediately. He’s reserved, cautious and calculated, and she’s an impulsive wild card. They couldn’t be more different, but somehow they work. Until they don’t. Joel is devastated to learn one day of a radical brain alteration technique that effectively removes the memory of an ex from your mind, and Clementine has taken the plunge. Joel is confused and lost, and while the iron is still hot in his beating heart, he decides to undergo the procedure as well. Then the film really turns your world upside down. Whilst the staff of the Institute (Mark Ruffalo, Elijah Wood and Kirsten Dunst) go to work on his mind in his sleep, he has a change of heart. With the memories of Clementine radidly disintegrating, he races through the internal landscape of his mind in order to find and save her, hiding her in obscure corners of his data log where she won’t be found. It’s a genius way to tell the story, taking a delightful turn for the surreal as both of them find themselves catapulted headlong into various moments of his life. On the outside, a tragic subplot unfolds involving Dunst and the the head doctor at the program (Tom Wilkinson). Kirsten and Tom have never been better, treating an often used trope with dignity and gentleness. For all its tricks and psychological whathaveya, the film is first and foremost about love. It isn’t interested in showing us any generic or clichéd depiction of it either, like most of the pandering fluff that gets passed off as romance these days. It strives to show love in all its brutal and painful glory, the fights, the hurt, the time spent alone, the resentment and the willingness to batter your way through all that, against better judgment and logic, if it’s worth it. Is love a force of its own, a measurable influence that can transcend a procedure like that? Is it it’s own element, or simply always a part of us? Carrey and Winslet (and, to a lesser extent, Wilkinson and Dunst) tenderly search for the answers to these difficult questions in what are the roles of a lifetime for both. Carrey has never been so vulnerable, so open, and despite his brilliant comedic work elsewhere, his performance here is a direct window into the soul, and his best work to date. Although the film is quite labyrinthine and jumps around quite a lot, it never, ever jumps the track or misses a beat. It’s always concise, deliberate and crystal clear, if you have the patience and dedication to watch it a few times in order to let all the beautiful images, words and ideas sink in. Movies are first and foremost for entertainment. You give the man your nickel, he fires up the projector and you watch the lone ranger chase down down a speeding locomotive. Every once in a while you get one like this, one that challenges and inspires deep thought, intangible feelings and teaches you something, maybe even about yourself. Every once in a while, you get one that alters your life, and that is what is so important about that little spinning machine that opens up worlds upon a simple flat white canvas where before there was nothing. A masterpiece.

Tag: charlie kaufman

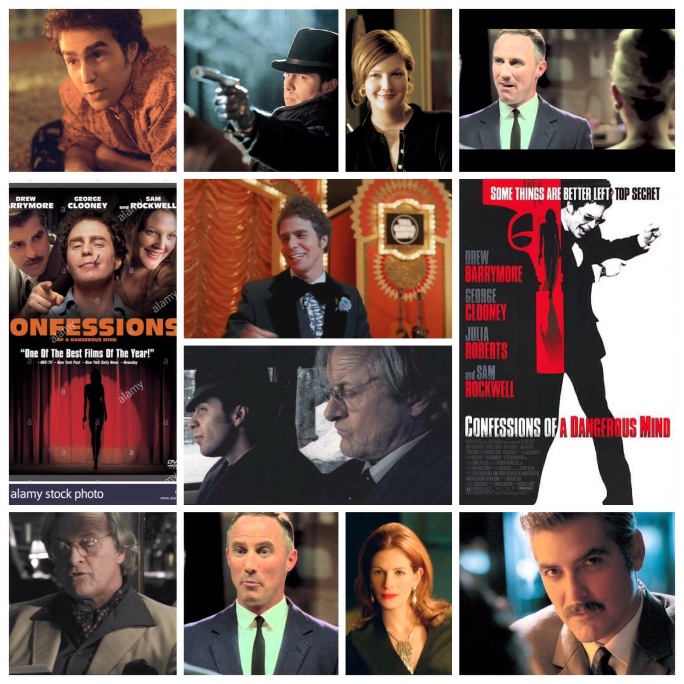

Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind: A Review By Nate Hill

As soon as George Clooney built up enough clout and reputation in the industry to a point where he could make his own projects, he started to send some unique and refreshing stuff down an assembly line that needed some shaking up. Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind is such a curiosity, but it’s so specific and idiosyncratic that I can barely say what makes it so special. I can go over the plot, performances etc. and give the reader a general idea, but to get it you had to be there. I suppose that’s the case with all movies, this one just sort of has its own frequency that you have to be tuned into. For a square jawed leading man, Clooney sure busted the box open with this directorial effort, as well as a few others, all just as distinctive. A screenplay by Mr. Abstract himself, Charlie Kaufman, helps with making an impression as well. Sam Rockwell, who continues to prove himself as one of the best actors of his generation, plays Chuck Barris. Chuck was the brain child behind numerous gaudy television game shows in the 60’s, including the infamous ‘Dating Game’. Flippant creative output was his brand, but there was another side to him as well, a darker period in which he claimed to be recruited by the CIA to carry out cloak and dagger assassinations. Whether or not this was ever a factual part of his life is murky, but he certainly believes it to be true and has written extensively about it in the novel which Clooney based this on. The film deftly intersperses his life at the television network and the genesis of the programs with his training and eventual missions for the Company. It’s an odd contrast, but when you’re treated with Clooney’s dutiful storytelling and an extremely committed turn from Rockwell, it’s hard not to be drawn into it. Not to mention the supporting cast. Julia Roberts is cast against type as a lethal, sociopathic femme fatale who crosses paths with Barris more than a few times. Rutger Hauer mopes about as a loveable alcoholic operative who covers Barris’s back on a few assignments. Drew Barrymore spruces things up as a ditzy love interest, Michael Cera plays Chuck as a young’in, Clooney himself underplays his CIA handler, letting an epic moustache do the talking, and there’s cameos from Maggie Gyllenhaal, Brad Pitt and Matt Damon. At one point the film stops dead in its tracks for the funniest performance which hijacks a scene briefly, in the form of Robert John Burke as a maniacal censorship board hyena. Burke pulls the ripcord and delivers roughly 40 seconds of pure comedic genius that I could watch on loop, and is the only moment of its kind in the film. You’d think it’d offset tone, but in a film this organic and quirky, it simply serves as a garnish of hilarity. The whole thing has a Soderbergh feel to it (perhaps due to Clooney), a sharp, crystalline precision to the burnished cinematography from Newton Thomas Sigel, who previously wowed us with similar work on Blood & Wine, The Usual Suspects and Gregory Hoblit’s Fallen. His lens captures the melancholy accompanying Barris’s very strange path path in life with moodily lit frames, and pauses for the brilliant moments of absurd black comedy which seem to follow him around like the spooks he was always running from. A film with dual aspects that never tries to prove or disprove Chuck’s claims, but loyally tells the story the way he told it, guided by Clooney all the while. A little stroke of genius.