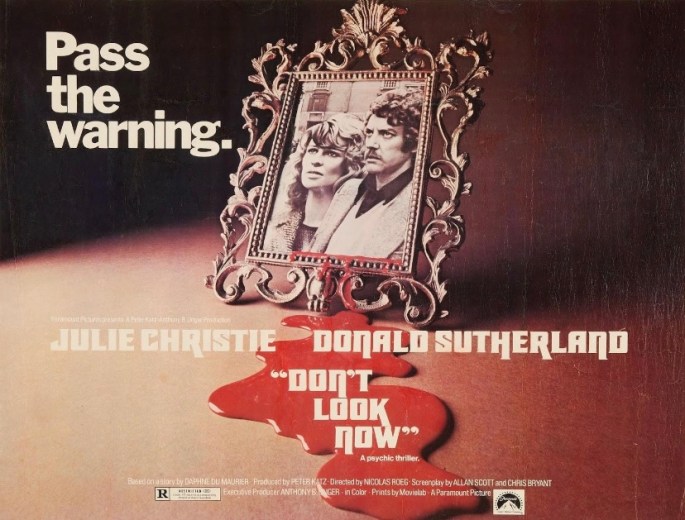

Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now is one continuous bad dream in the best possible way, a chilly European nightmare that begins with a couple (Donald Sutherland & Julie Christie) losing their young daughter in a drowning accident and the subsequent mental trauma, bad luck and eerie visions that plague them one year later as he works to restore a Venice church for a malevolent Bishop (Massimo Serato) who notices his strange behaviour and she refuses to let go, taking up with three odd clairvoyant sisters who can apparently communicate with the dead. This is a moody piece to its very bones, the story itself could be told in several clipped beats or so but the real substance lies in the moments in between dialogue, the spectral apparitions they see running about the cluttered, labyrinthine Venice streets and their collective inability to let go of their shared tragedy manifested in the physical realm as terrifying apparitions. We sense this pain lingering over them both in a sex scene that is too strange to describe, a montage of sorts that feels sweet and awkward and carnal in a primordial sort of way, like a Lite version of the ferocious, voodoo tinged Mickey Rourke & Lisa Bonet sex scene in Alan Parker’s Angel Heart, but no less unsettling and otherworldly. There’s a subplot about a serial killer in a little red jacket running loose, a jacket that looks suspiciously like the same one their kid was wearing when she drowned, which doesn’t help their overall mental state and provides one of the most frightening, heart attack inducing scenes I’ve ever seen in horror. Sutherland and Christie are both phenomenal here, the former adopting a feverish workaholic denial to avoid facing his pain and the latter stuck in a hyper-emotional terrain of manic and depressive episodes, hopeless hills and valleys of grief, confusion and despair. Venice has never looked more menacing here, the edifices, ancient structures and sentinel churches standing austere watch over these two lost souls, like a meticulously carved dream world of chilly fog, dead ends and kaleidoscopic stained glass backdrops. I can see why this has become such a classic and gone on to influence so many other great artists in horror pop culture, I can imagine everyone from David Lynch to the creators of Silent Hill were inspired. Dark, brooding, atmospheric meditation on loss and grief shot through the disorienting, beautiful and frighting prism of a ghost story, absolutely great film.

-Nate Hill