Filmed in “beautiful” Portland, Oregon, Drugstore Cowboy (1989) is an unapologetic look at the life of a junkie during the early 1970s. As the film opens we see the protagonist, Bob (Matt Dillon), flat out on a stretcher in a speeding ambulance. He stares at the camera and his voice narrates, “I was once a shameless full-time dope fiend.” It is this confessional voice that sets the tone for the rest of the film as Bob takes us back in time to show how he reached his current state. He was the leader of a gang of drug users who robbed drugstores to maintain a constant high.

The gang follows a family mentality with Bob acting as the street smart “father,” and Diane (Kelly Lynch) as the “mother” who keeps everyone else in line. “I loved her, and man, she loved dope,” Bob remembers. Rick (James Le Gros) is the “son,” a quiet guy who clearly views Bob as a father figure. Nadine (Heather Graham) is Rick’s wife, the “daughter” figure, and a recent addition who is forever trying to prove her worth to the others. Director Gus Van Sant introduces this “family” in a great opening scene where they work together to rob a drugstore in broad daylight. Each one enters the store, apparently by themselves, each casing the place, waiting until Nadine provides the signal – a faked epileptic fit that draws everyone’s attention, leaving Bob free to sneak behind the counter and take the drugs. The plan is flawlessly executed with Diane even having the time to steal a paperback novel from a rack.

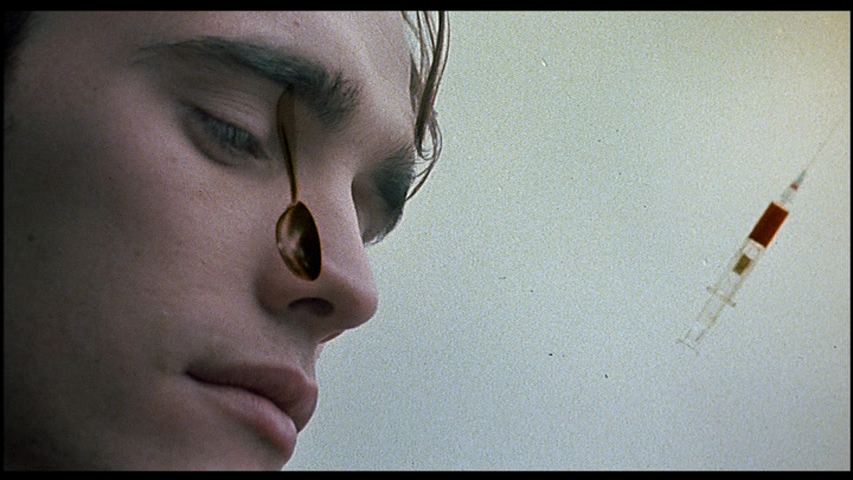

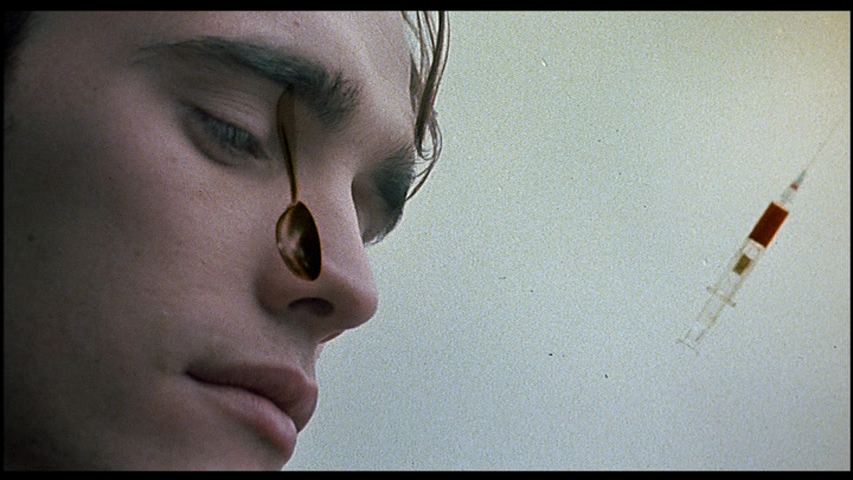

As the group flees the scene in a getaway car, Bob shoots up in the back seat and Van Sant uses this action to enter Bob’s head and show us the worldview of a junkie. As the drug takes hold Van Sant has the real world fade into the background and a dreamy, surreal world filled with floating syringes, spoons and houses complete with a hypnotic, monotone rap of a stoned Bob narrating the action: “Upon entering the vein, the drug would start a warm edge that would surge along until the brain consumed it in a gentle explosion that began at the back of the neck and rose rapidly until I felt such pleasure that the whole world sympathized and took on a soft, lofty appeal.” It’s a dreamy logic that seems to suit Bob’s own little world perfectly. In fact, much of the film is seen from Bob’s viewpoint. Van Sant takes the basic ritual of shooting up and focuses in on the primary components: extreme close-ups of the pills, a lit match, and a syringe sucking up the drugs off a spoon. It is almost like we are preparing for a fix right along with Bob.

And yet for such an accurate portrayal of the highs of drug use, oddly enough Van Sant does not show Bob or any of his crew in the throes of withdrawal, especially when, later on, he decides to go straight. While some of the negative aspects of this kind of life are shown, like people dying, the film refuses to show what happens when one tries to stop using drugs, unlike, say Trainspotting (1996), which does it so well and with such frightening intensity. What sets Drugstore Cowboy apart from other films about drug users are nice little touches like Bob’s superstitions: dogs, hats on beds and, strangely enough, looking at the back of mirrors. It is the hats, however, that is the most important hex and one that comes back to haunt him later in the film.

Matt Dillon does an excellent job of portraying someone high on drugs, in particular, the scene where Bob has taken speed. The actor nails all of the fidgety mannerisms, like clenching his job repeatedly. In Dillon’s long, illustrious career, this performance is his most relaxed and naturalistic. He gives Bob a cool, confident swagger that seems so right for the character. Dillon presents Bob as a smart person, always thinking ahead, always one step ahead of the law. He’s smart because as he says, “I just know, from years of experience, the things to look for, the signs…All you gotta do is look for the signs.” It is this ability that keeps him on top of his game. Dillon’s voiceovers are particularly effective in filling in the gaps and giving little tidbits of junkie culture. There is no wall between him and the camera and there are no artificial mannerisms in his performance.

The rest of the “family” is also excellent, in particular Kelly Lynch who is the perfect foil for Dillon. Diane’s role in the crew is evident in the way she deals with the other members. For example, when she steps in and breaks up a heated argument between local speed-freak David (Max Perlich) and Bob, it is like a mother breaking up a fight between two little boys fighting over a toy. James Le Gros is a greatly underappreciated character actor who dabbles in mainstream films like Point Break (1991) and Zodiac (2007), usually in small roles, and meatier parts in independent films like Living in Oblivion (1995) and Scotland, PA (2001). In Drugstore Cowboy, he plays Bob’s inexperienced right-hand man and protégé. At first, Rick seems a little on the dumb side as he speaks simply but there’s more to him. Le Gros spends a lot of time watching Bob and learning as becomes evident later on. Rounding out the crew is Heather Graham as Nadine. Before her performance as Rollergirl in Boogie Nights (1997) launched her career on a mainstream level, she had a memorable turn as Agent Cooper’s doomed love interest in Twin Peaks. She’s good as the hopelessly naive and inept member of the crew and her sole purpose is to be a pain in Bob’s ass but you kind of feel sorry for her at times.

James Remar brings a real sense of humanity to what could have been a stock cop role. He usually plays bad guys (48 Hrs.) or disreputable types (The Warriors) and gets to show off his range with Gentry in Drugstore Cowboy, playing a cop trying to bust Bob and his crew. At first, he comes across as a typical antagonist, always giving Bob a hard time but something happens over the course of the film. As Bob attempts to kick his drug habit, Gentry becomes a more sympathetic figure. He recognizes that Bob is trying to make an honest go of things and supports him in his own way.

What would a film about junkies be without a cameo by the king of them all, William S. Burroughs who plays a defrocked priest. Van Sant uses Burroughs as a sort of prophetic figure who delivers a sage monologue on the future of drugs: “Narcotics have been systematically scapegoated and demonized. The idea that anyone can use drugs and escape a horrible fate is anathema to these idiots. I predict, in the near future, right wingers will use drug hysteria as a pretext to set up an international police apparatus.” The legendary writer apparently wrote all of his own lines and it shows, as these words seem like vintage Burroughs, coming right off the pages of Naked Lunch. His presence also helps give the film an authenticity.

Drugstore Cowboy is a film filled with strong performances, and stunning cinematography as Van Sant mixes Super 8mm with 35mm, using time lapse photography with elements of surrealism to create a world as seen through the eyes of a junkie. Van Sant does not judge his characters, he merely presents them as they are and leaves it up to the audience to make their own minds. Even though the film deals with depressing subject matter it never dips down the murky level of a film like Sid and Nancy (1986), but rather offers a ray of hope at the end as Bob tries to come clean and kick his habit. It won’t be easy for him, but at least he has a chance to give it a shot.

Drugstore Cowboy is a film filled with strong performances, and stunning cinematography as Van Sant mixes Super 8mm with 35mm, using time lapse photography with elements of surrealism to create a world as seen through the eyes of a junkie. Van Sant does not judge his characters, he merely presents them as they are and leaves it up to the audience to make their own minds. Even though the film deals with depressing subject matter it never dips down the murky level of a film like Sid and Nancy (1986), but rather offers a ray of hope at the end as Bob tries to come clean and kick his habit. It won’t be easy for him, but at least he has a chance to give it a shot.

Drugstore Cowboy is a film filled with strong performances, and stunning cinematography as Van Sant mixes Super 8mm with 35mm, using time lapse photography with elements of surrealism to create a world as seen through the eyes of a junkie. Van Sant does not judge his characters, he merely presents them as they are and leaves it up to the audience to make their own minds. Even though the film deals with depressing subject matter it never dips down the murky level of a film like Sid and Nancy (1986), but rather offers a ray of hope at the end as Bob tries to come clean and kick his habit. It won’t be easy for him, but at least he has a chance to give it a shot.

Drugstore Cowboy is a film filled with strong performances, and stunning cinematography as Van Sant mixes Super 8mm with 35mm, using time lapse photography with elements of surrealism to create a world as seen through the eyes of a junkie. Van Sant does not judge his characters, he merely presents them as they are and leaves it up to the audience to make their own minds. Even though the film deals with depressing subject matter it never dips down the murky level of a film like Sid and Nancy (1986), but rather offers a ray of hope at the end as Bob tries to come clean and kick his habit. It won’t be easy for him, but at least he has a chance to give it a shot.