The subject of mental illness is one that’s close and important to me as I myself am one of the afflicted, and it’s impossible to ignore that the treatment of it by Hollywood, particularly in formative years, hasn’t been so apt. Don’t get me wrong, I love stuff like Me, Myself & Irene or Split as entertainment but in terms of accurately representing the conditions that beset human beings, they haven’t been so hot. There are those films and filmmakers out there that strive to educate and enlighten or even just to craft an effective thriller or comedy and still stay true to real life, doing important work for the collective awareness and making terrific art/entertainment in one shot. Here are my personal top ten favourites!

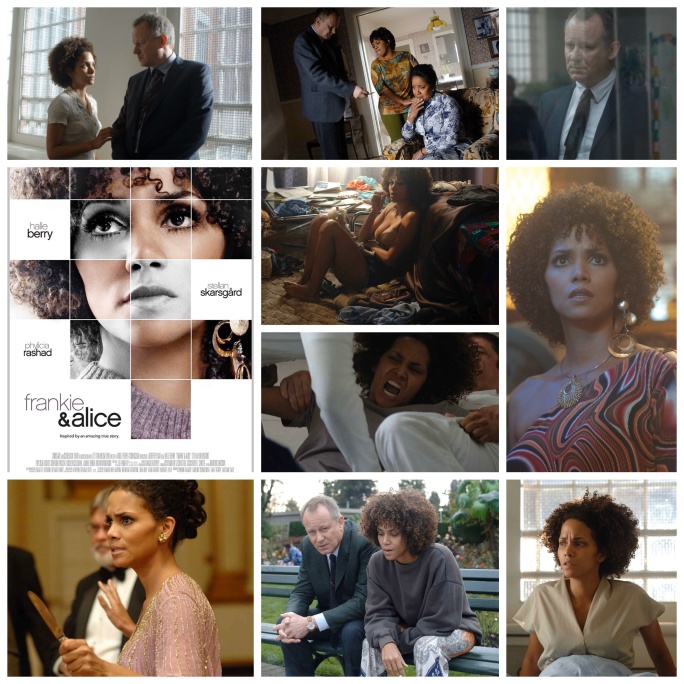

10. Geoffrey Sax’s Frankie & Alice

Multiple personality disorders are popular in Hollywood but there’s a tendency to mock, sensationalize or tell a ‘real life’ story that’s later proved as fraud. This one showcases Halle Berry in a galvanizing dual performance as a go-go dancer afflicted by two very different internal identities and finding her life in splinters as a result. When a kind, compassionate psychiatrist (Stellan Skarsgard) makes it his mission to help her get back on track it becomes apparent just how challenging and horrific it must be to endure such a thing.

9. Dito Montiel’s Man Down

I heard this one sold one single theatrical ticket in the UK and didn’t fare much better here, getting squeaked into a quiet streaming release. It’s too bad because it is one haunting drama about PTSD featuring an implosive, incredibly intense performance from Shia LaBeouf as an ex marine who can’t psychologically reconcile his experience and is lost amongst his own trauma. Terrific work from Kate Mara as his wife and Gary Oldman as an army counsellor too.

8. James Mangold’s Girl Interrupted

Likely the most accessible and mainstream story on this list, Mangold’s look at a mental care facility for girls in the 60’s gets a superficial rep in some circles but I find it to be every bit the rewarding drama, ensemble piece and explorative journey that those who champion it say. Winona Ryder plays a wayward girl whose self destructive behaviour lands her there but it’s Angelina Jolie as a fellow patient diagnosed with borderline personality disorder that both anchors the film and provides it with a wildly unpredictable streak.

7. Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island

This is of course a big old elaborate mystery film with a gigantic cast, many red herrings, tons of subplots and all kinds of stylistic fanfare. But if you look past all that there’s a harrowing and very realistic portrait of minds irreparably damaged, between Leo Dicaprio’s PTSD afflicted ex soldier and Michelle Williams in a haunting turn as his deeply sick wife. The film overall is a tantalizing guessing game and broadly covers the thriller board but the final act brings it right down to earth for a grounded, grim finale showcasing the brutal honesty of these illnesses and the heart wrenching tragedy they beget.

6. Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King

Robin Williams gives one of his best performances as Parry, a once successful professor of medieval history who lost his mind following the death of his wife and now wanders the streets of NYC, homeless. Jeff Bridges is the radio DJ who befriends and tries to understand him and their relationship carries the film. So to does Gilliam’s knack for surreal visual storytelling, letting these fantastical creations run wild and giving us a glimpse into Parry’s damaged but fascinating mind.

5. Brad Anderson’s The Machinist

Christian Bale’s Trevor Reznik hasn’t slept in a year. Guilt, extreme weight loss and delusions are just the start of his problems. This is billed as and feels like a thriller but I think that’s deliberate on director Anderson’s part to put us in the hot seat next to Trevor, to make us feel the same paranoia and delusions of persecution he does. The atmosphere here is almost suffocating, the score a muted tangle of busted nerves and Bale’s performance something just this side of unearthly. When it all comes together and we see why he is the way he is it’s deeply sad but makes a kind of terrible sense and gives the film a final stab of emotional weight.

4. Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace

PTSD is only vaguely hinted at in this beautiful father daughter drama but it’s there in every frame, in every mannerism of Ben Fosters masterful performance. Him and newcomer Thomasin Mackenzie achingly display a family dynamic that has been set off balance by his illness, and the wedge it has driven both between them and between him and ever living a normal life again. This is a restrained yet heartbreaking film that gently unpacks its themes with kindness and compassion, letting a devastating final scene bring the whole point home heavily but somehow lightly in the same note.

3. David Cronenberg’s Spider

Ralph Fiennes give a focused, intense turn as the titular individual, a man released from a mental care facility and relegated to a London halfway house where all the scrambled and tumultuous memories of his past come tumbling down through the scattered web of his broken mind and into the present. Recollections of his parents (Gabriel Byrne and Miranda Richardson) are somehow shrouded from himself, by himself and as he tirelessly works to regain his sanity, he slips further away from it. Cronenberg uses shadows, dimly lit alleys and creaky, barren rooms to show how this character has been cast away from his own perception and wanders about like a lost soul.

2. Bill Pohlad’s Love & Mercy

The life and times of Beach Boys pioneer Brian Wilson are explored here, namely at two important junctures in his life. Paul Dano plays him younger, at the height of fame and success but poised on the cusp of a psychotic breakdown after stress and an unhealthy relationship with his abusive father (Bill Camp) reach a fever pitch. Decades later John Cusack embodies a much older Wilson, stuck under the tyrannical yoke of an evil, manipulative psychiatrist (Paul Giamatti) until he meets the love of his life (Elizabeth Banks) and a chance at a fresh start along with her. The scene of Dano putting recording headphones over his ears and closing his eyes in horror as he hears voices is one of the most brutally honest and realistic depictions of auditory hallucinations you can find in film. Wilson had a rough life and the film makes that very clear but it’s never ever sensationalist or exploitive and overall has a message about love, light and working endlessly to overcome any demons or struggles thrown into your path.

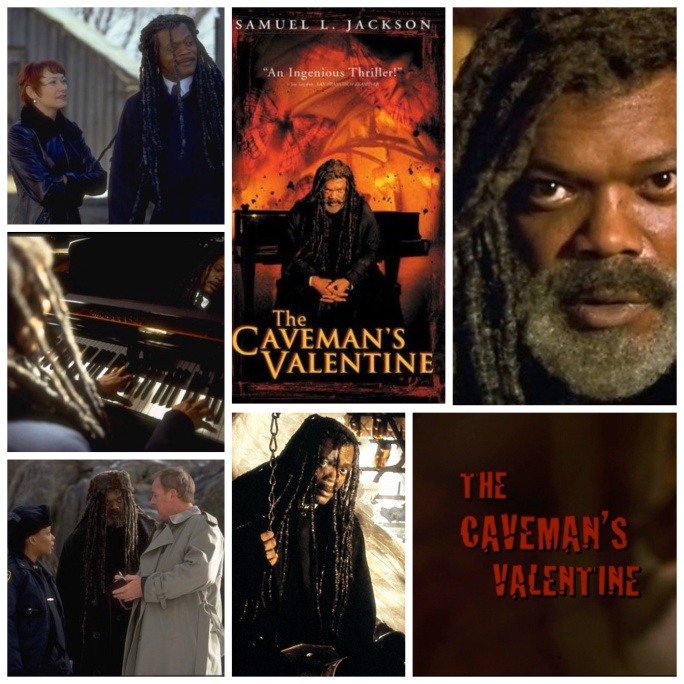

1. Kasi Lemmons’ The Caveman’s Valentine

Samuel L. Jackson gives a career best as schizophrenic former musician Romulus, a man afflicted by terrible hallucinations and delusions to the point that when he discovers a genuine murder conspiracy no one, including his police officer daughter (Aunjanue Ellis) believes him. This film is driven by a fascinating mystery narrative that takes Romulus from his cave in Central Park into the pretentious New York art world and beyond to find a killer. At heart though director Lemmons let’s it m be a serious minded exploration of what it must be like to live like that, to be constantly sabotaged by your own mind. Jackson’s brilliant performance and Lemmons effective use of surreal, mesmerizing imagery give us a compassionate, dynamic window into this man’s mind and in turn a unique, thought provoking piece of cinema.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for more content!

-Nate Hill