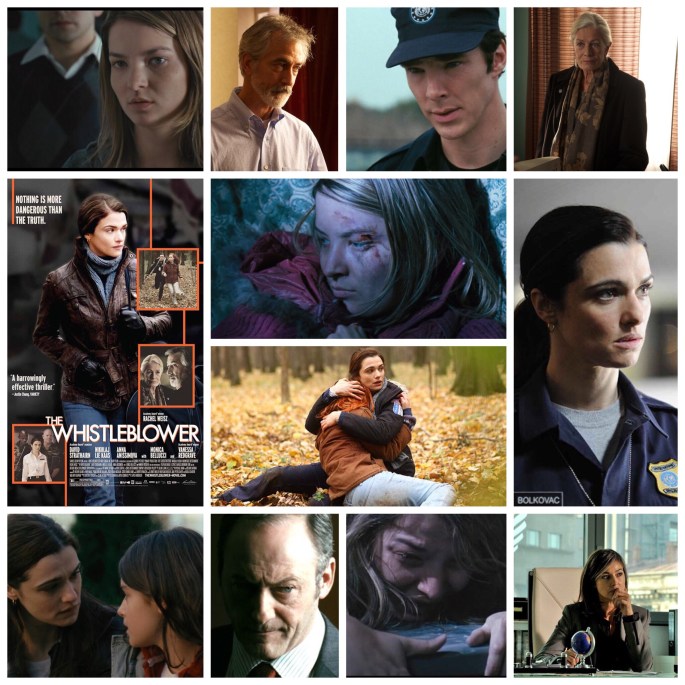

Larysa Kondracki’s The Whistleblower requires a strong stomach to sit through some of the true life atrocities depicted, but it also begs that one doesn’t look away, or the efforts of one intrepid UN worker (Rachel Weisz) would have gone unheeded, because almost everyone else besides her turned a blind eye when scores of young woman in post war Bosnia were being held captive and brutalized in the illegal sex trade. I can’t think of anyone more adept than Weisz at playing someone this relentlessly compassionate; there’s just something in her warm brown eyes, comforting voice and genuine aura that that camera and dialogue practically melt over. Horror like this almost always follows the fog of war, when the barriers of civilization have taken a hit and the darkness they held at bay roams free for awhile, plus it’s hard to keep track of people after something like that wipes records, destroys towns and fucks up infrastructure. In any case, Weisz’s Kathryn Bolkovac discovers dozens of underground brothels where young girls are held, raped and tortured by mercenaries every day. Her boss at the UN (Liam Cunningham in a chilling portrait of casual indifference) tells her to lay off and they they’re “whores of war, that’s how it works.” Faced with that kind of betrayal from her own people snaps something in Kathryn and she feels deeply compelled to launch her own personal crusade to save the girls, but it proves to be a dangerous task when she realizes that not only do organizations not really care, but some may actively have interests in stopping her. Using contacts in various departments including Monica Bellucci, a kindly Vanessa Redgrave, Benedict Cumberbatch and a fantastic David Strathairn, she gradually gets to the centre of this evil maze, towards truth and freedom for hundreds of innocent girls. The great thing about this film is that it functions as both a superbly exciting political thriller in the vein of Bourne, but really it’s a deeply human, very personal and harrowing study of evil taking root in a region, as the light that Kathryn keeps in her heart wth which to fight it. This is represented in a key relationship between Kathryn and a young Bosnian girl named Raya (Roxana Kondurache, phenomenal) who she takes a special interest in and becomes poster child for these girls. Also, it’s a very carefully researched true story too and that always makes events like this far more affecting onscreen. Just go in with the right mindset and guardrails up because the scenes of sexual abuse and torture are almost unbearable, but necessary to the story arc. A winner in every sense of the word.

-Nate Hill