Circa 1956, young Gabriella is brought to the estate of Dr. Meyer, who believes that the girl harnesses supernatural powers and intends to put them to good use during one fateful night. After accompanying her to the basement, where she begins writhing about on the dirt-covered ground and is then attacked by something unseen when left alone, Meyer deduces that the area they’ve stumbled upon is what is known as a “K Zone” upon realizing that the man who infamously studied them, Paolo Zeder, was buried underneath the house some years ago.

Favoring petrifying ambiance over surface-level schlock, though impartial to entertaining the latter when apt, Pupi Avati’s horror films are characteristically infused with a kind of sinister, otherworldly energy; as if the man responsible for them always has one foot in reality and the other in the spirit world. In this sense, ZEDER (aka REVENGE OF THE DEAD) is straight from the heart of its maker, being (among other things) a film that deals directly with those disconcerting voices from beyond and why they are necessary to a superior understanding of our surroundings.

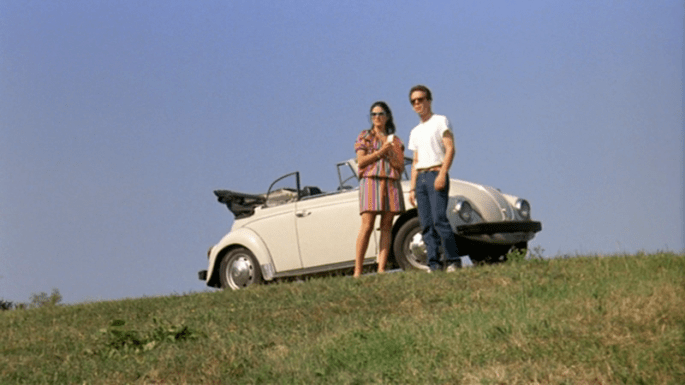

Following such a uniquely enigmatic opening, we are introduced to Stefano (Gabriele Lavia), a young novelist living in present day (1983) Bologna. He comes home one day to a surprise anniversary gift from his wife Alessandra (Anne Canovas) in the form of an old typewriter which he can’t help but test drive that same evening. Upon closer inspection of the ribbon housed inside the apparatus, he discovers an essay written by the aforementioned Zeder and becomes increasingly obsessed with the man’s studies.

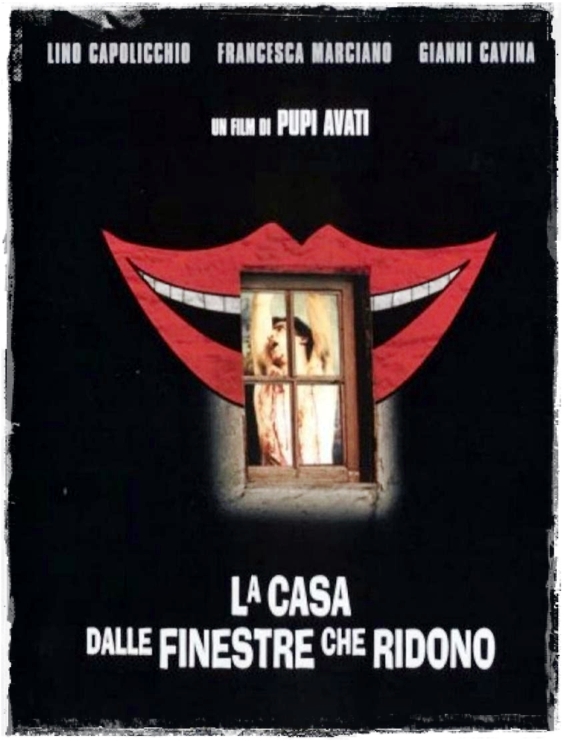

Similarly to Avati’s masterful giallo THE HOUSE WITH THE LAUGHING WINDOWS, the unlikely hero often feels alone in the world. Whenever Stefano attempts to inquire about Zeder and his finds, even the most reputable members of society turn him away; and when he decides to take matters into his own hands, they tend to get a bit dirty. He must be careful who he talks to, for their lives may be endangered if he does so.

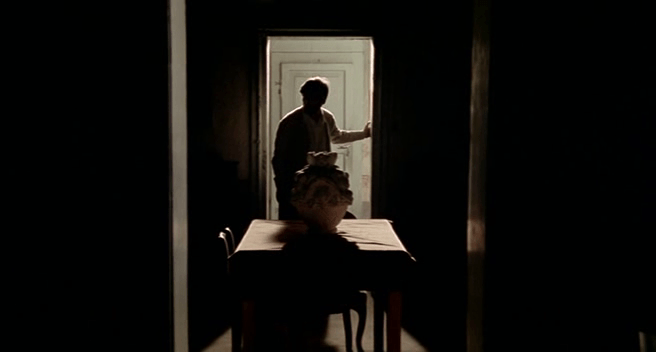

Without showing too much, Avati manages to get deep under your skin; take the K-Zones, for instance, which have something to do with reanimation, and yet that specific “something” is never explored in explicit detail. However, it’s undoubtedly better off this way. The horrors of ZEDER, beautifully rendered as they are, seem rooted in paranoia and guilt on a profoundly national scale; the film is like an exorcism for all of Italy, albeit one where the cleansing of body and soul is secondary to the painful possession of Avati’s fellow countrymen and how they attempt to evade it. While Stefano pursues the mystery at hand, Gabriella (now an adult) and Meyer scheme – it would be unwise to trust that anyone, even those closest to you, are not in on it in some way. It’s an angry, poignant, and indeed genuinely frightening state of affairs – assuming one is enticed by implication.

European horror films tend to wear their imperfections on their sleeve, and ZEDER is no exception. Franco Delli Colli’s (RATS: NIGHT OF TERROR, MACABRE, STRIP NUDE FOR YOUR KILLER) cinematography is luscious, Riz Ortolani’s score is typically fierce, the make-up effects – particularly for the undead – are refreshingly subtle, and yet there are flaws to be found in Amedeo Salfa’s editing. On a whole, the film flows exquisitely – but once in a while there’s an abrupt transition which threatens to soil an otherwise divine experience; and although this is easily redeemed, it can’t help but pale, if only slightly, in comparison to its aforementioned cinematic brethren as a result.

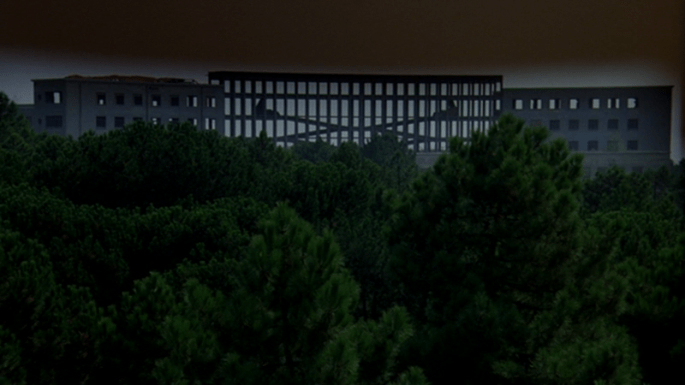

But oh, what sights Avati has to show you. From the abandoned soon-to-be-hotel which marks the high point of Stefano’s journey and the dusty tunnels running underneath to the young couple’s sleek, secure apartment, it’s remarkable how distinctive each location feels and how well the director utilizes them throughout. One feels alienated regardless of where they find themselves; the world is wired by phantoms. As is the case with some of the best, this is a film about man’s relationship with time and place in unison with his personal affairs; while the romance at the center of the story gives it a much-needed emotional backbone, it’s ultimately a vision of our ever-changing landscape and how we choose to confront those sudden transitions.

Admittedly, this could potentially disappoint viewers expecting a gorier, more straight-forward zombie yarn, but what a thing to behold. Avati has contributed something that goes far deeper than exceptional genre cinema, knowing all too well that mystery and tragedy alike account for many of the things in life which are most difficult to swallow. Some questions cannot be answered, or so the director seems to conclude at the end of this macabre tale. We can only seek so much truth before we bump up against our own limits.