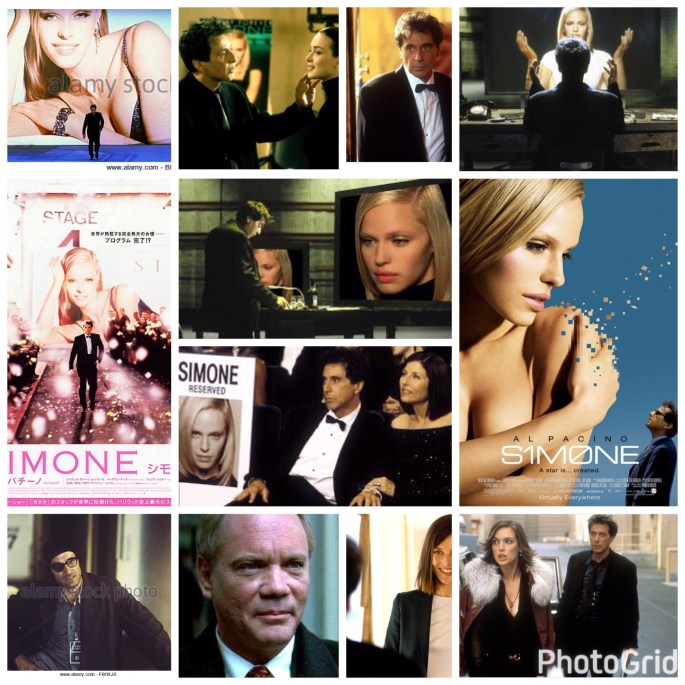

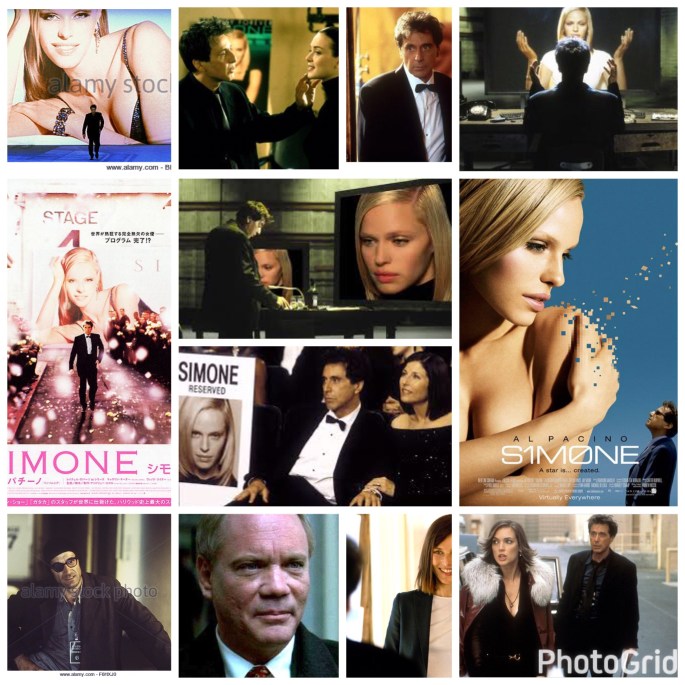

Andrew Niccol’s S1mone is social satire at its cheeriest, a pleasant, endearing dissection of Hollywood mania and celebrity obsession that only hints at the level of menace one might achieve with the concept. It’s less of a cautionary tale and more of a comedic fable, and better for it too. In a glamorous yet used up Hollywood, mega producer Viktor Taransky (Al Pacino with some serious pep in his step) needs to give his enterprise a makeover. His go-to star (Winona Ryder) is a preening diva who drives him up the wall, and there seems to be a glaring absence of creative juice in his side of the court. Something cutting edge, something brand new and organic, something no one else has. But what? Simone, that’s what. After finding clandestine software left behind by a deceased Geppeto-esque computer genius (Elias Koteas, excellent), he downloads what lies within, and all manner of mayhem breaks loose. The program was designed to create the perfect virtual reality woman, flawless and capable in every way, including that of the cinematic thespian. Viktor sees this as gold and treats it as such, carefully introducing Simone (played by silky voiced model Rachel Roberts) to an unsuspecting film industry who are taken by storm and smitten. Simone can tirelessly churn out five oscar worthy performances in a month, never creates on set drama, whips up scandals or demands pay raises. She’s the answer to everyone’s problem, except for the one issue surrounding her very presence on the screen: she isn’t actually real. This creates a wildly hysterical dilemma for Pacino, a fiery Catherine Keener as a fellow executive, and everyone out there who’s had the wool pulled over their starry eyes. It’s the kind of tale we’d expect from Barry Levinson or the like, a raucously funny, warmhearted, pithily clever send up of the madness that thrives in the movie industry every day. There’s all manner of cameos and supporting turns including Evan Rachel Wood, Jay Mohr, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Jason Schwartzman, Rebecca Romjin and the late Daniel Von Bargen as a detective who cheekily grills Pacino when things get real and the masses want answers. This is fairy tale land in terms of plausibility, but it’s so darn pleasant and entertaining that it just comes off in a relatable, believable manner. Pacino is having fun too, a frenzied goofball who tries his damnedest to safeguard his secret while harried on all sides by colleagues and fans alike. Roberts is sensual and symmetrical as the computer vixen, carefully walking a tightrope between robotic vocation and emoting, essentially playing an actress pretending to be an actress who isn’t even human, no easy task. It’s a breezy package that’s never too dark or sobering, yet still manages to show the twisted side of a famously strange industry. Great stuff.

-Nate Hill