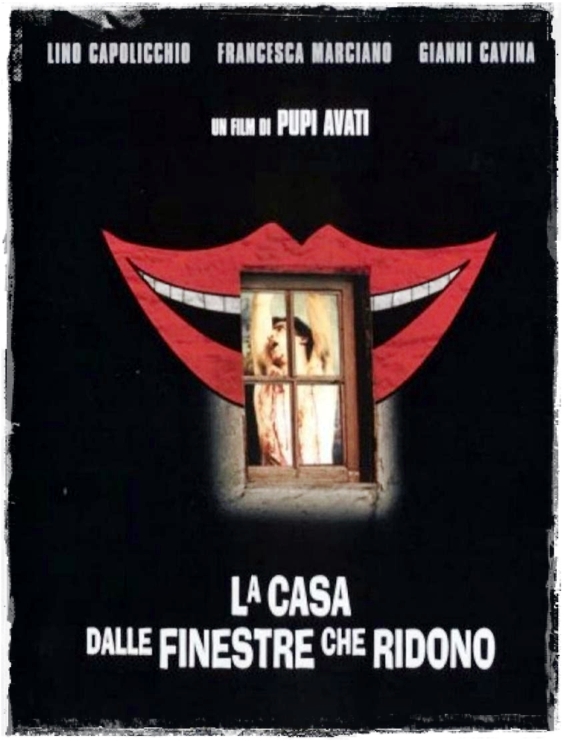

George A. Romero is – or at the very least once was – the kind of socially conscious filmmaker the horror genre is in dire need of these days. His early films are the most blunt, angry, and effective in his oeuvre; though few would deny they are rough around the edges, their energy and ambition is nonetheless infectious. Sandwiched between NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, Romero’s little-seen sophomore effort (1971’s THERE’S ALWAYS VANILLA, a romantic comedy), and 1973’s THE CRAZIES is SEASON OF THE WITCH (known as JACK’S WIFE when it was in production, and before the distributor excised half an hour from its run-time), a surprisingly thoughtful musing on contemporary witchcraft, repressed sexuality and the patriarchy; an endlessly fascinating, mostly successful marriage of talky, sleazy soap opera aesthetics and surreal psych-out horror.

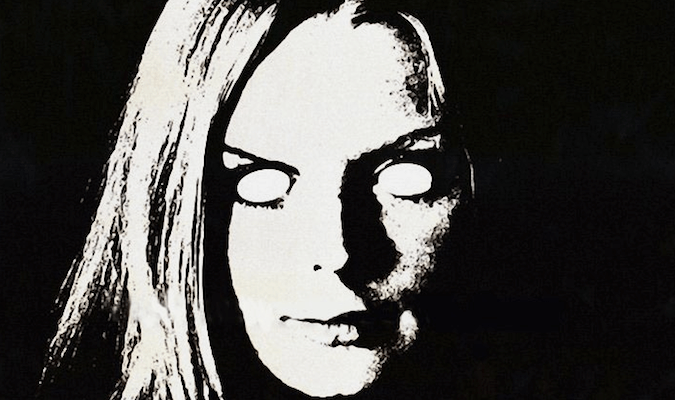

Joan Mitchell is a bored housewife facing a mid-life crisis. Her husband Jack has little time for intimacy, there’s a considerable distance she feels between herself and their daughter Nikki, and she has recurring nightmares in which Jack aggressively pays her no mind and she envisions herself as a pale-faced old hag. The psychotherapist she’s been regularly seeing feeds her the same old crap in response to her attempts to understand these dreams (“The only one imprisoning Joanie…is Joanie.”), Nikki’s seeing more action in her week than Joan surely has in years, and things are just overall rather drab.

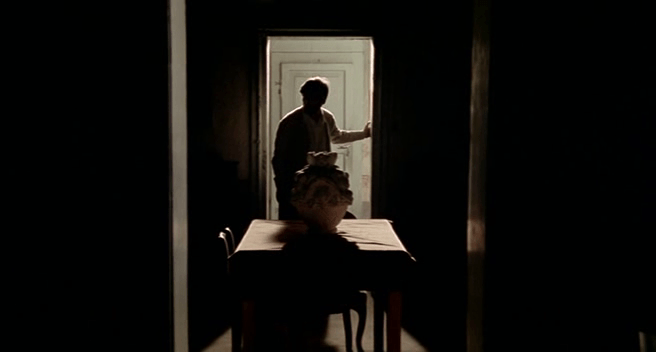

If nothing else, Joan’s got her circle of friends – a tightly knit community of fellow housewives who seem to share many of her anxieties. One evening at a dinner party, there’s talk of a new woman on the block that practices witchcraft. Joan, along with her closest friend Shirley, seeks her out and gets a Tarot reading, which surely opens up a couple of doors for them both. As Jack goes away on business, leaving her to her own devices, and terrible nightmares – in which a masked assailant breaks into the house and rapes her – continue to plague Joan’s mind, she dabbles in the occult as a way of reclaiming her sanity.

It wouldn’t be revealing too much to say that this is a film about – many things, but most importantly – a woman transcending her role in the household and discovering a new identity that has, in fact, been with her all along. Sexual identity, as is the case when Joan starts an affair with a teacher at Nikki’s school who had previously seduced her daughter as well and finds solace in the young man’s spirit, and personal identity go hand-in-hand. There’s also an emphasis on the pointlessness of the so-called “necessities” of life when one doesn’t truly believe in them, and at the beginning of this tale, Joan doesn’t believe in much of anything.

As evidenced in the opening dream sequence, Romero gives it you straight in regards to what the themes are here – to a fault, it could be argued, as Joan wearing a leash and collar, led on by Jack, and being locked inside a cage is a bit much – but regardless of how obvious they may be, they remain as relevant now as they were then. There’s a lot more dialogue than action, to be sure, but this is the kind of film where all the talking somehow manages to get us somewhere in the end, somewhere that feels on a whole satisfying and even intellectually stimulating. Audiences didn’t embrace the film upon its initial release, though Romero can hardly be faulted; marketed as some of kind of softcore porno in its severely cut form as HUNGRY WIVES, it would be difficult to make something this smart and genuinely challenging seem exciting to purveyors of provocation. Romero’s original 120-minute version may have been left on the cutting room floor but what resurfaced in 2005 with the help of the good folks at Anchor Bay seems like a damn fine representation of his intentions in its own right. We’ve changed with the times, and the time for SEASON OF THE WITCH is now. Better late than never, as they say.

At the very least, this is an ambitious cinematic cocktail, and for the most part it works. No doubt most people won’t find it to be all that visually stimulating, but if it really is about what you do with what you’ve got, Romero is a miracle worker. As cinematographer and editor as well as writer/director, he establishes an intoxicating rhythm early on that luckily remains consistent throughout – there are some really neat tricks employed during the post-production stage, as well as some creative camera movements which keep the proceedings from becoming mundane, even when the story doesn’t seem to be moving forward. This is a chilly film, perfect for viewing during the Fall season, and once Donavan’s titular song blares over an occult shopping spree, Romero’s unique alchemy has all but won you over. It’s very much of its time – the fashion, the unquestionably ugly décor, the hep terminology – and appreciation may vary based on one’s tolerance of this kind of stuff, but a thoughtful viewer will surely find plenty to chew on here, if not even more to swallow.