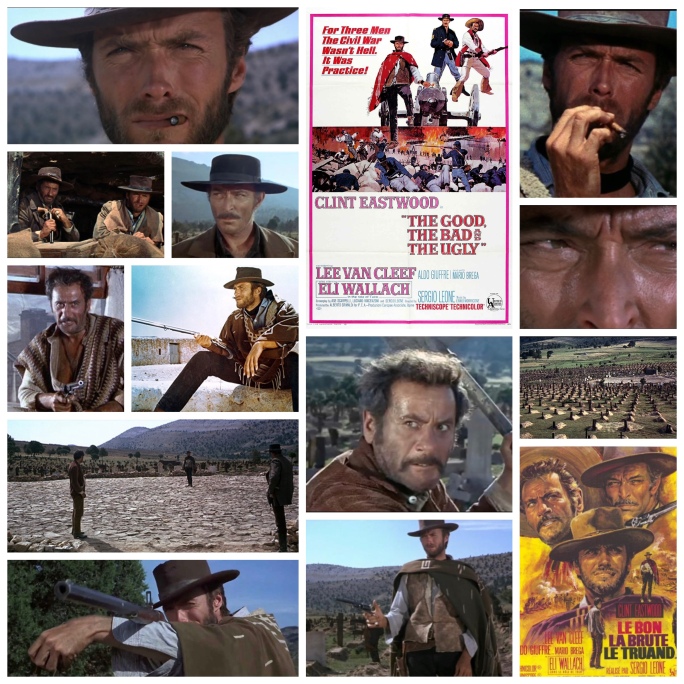

How iconic has the image become of Clint Eastwood, poncho adorned, rolled cigarette locked firmly in that drawn snarl, peering out from a wide brim, dust caked hat atop a horse? The Man With No Name is such a household name these days that he’s shown up everywhere from Stephen King lore to an animated Johnny Depp movie, but it all began with Sergio Leone’s original spaghetti western trilogy, the best of which is the fireball classic The Good, The Bad & The Ugly.

The trilogy itself not only launched an entire sub-genre in the early sixties but created a mood, a feel that no one besides Leone has ever been able to so specifically distill. Extreme closeups on eyes deep set in furrowing brows. Languid establishing shots of frontier town streets, expansive railroads and acres of dry brush-lands. The actors aren’t necessarily blocked from scene to scene with any kind of briskness but rather wade languidly through an ambient space seemingly at their own leisure and never with haste. Spaghetti westerns are never about the plot, but about the moment, the setup, the apprehension in the saloon, grotto, civil war torn graveyard or desert that these hard bitten folks find themselves in.

Eastwood’s nameless gunslinger meanders across a bitter, busted up American west that is, of course, actually Italy, engaging in war games and an obsessive treasure hunt with two other pieces of work, the sociopathic monster Angel Eyes (Lee Can Cleef) and the lecherous, untrustworthy rodent Tuco (Eli Wallach). All three are after a legendary gold stash somewhere out there in the desolation and are prepared to kill anyone who stands in their way, bonus points for each other. Eastwood is cold, calm and opaque, Cleef is cheerfully, sadistically ruthless, Wallach oozes weaselly survival instinct and together they make a captivating trio.

Three scenes in particular stand out in my mind; the first is the epic showdown between them all, stood a few hundred paces apart in a triangle, locked in a tense pre shootout stare-down as Ennio Morricone’s gorgeous and threatening score booms around the landscape and plays with expectations wonderfully. It’s a kicker of a scene and probably the showcase Western showdown in cinema. The second (and I’m assuming at this point that anyone who’s read this far has seen the film) is the final sequence where Eastwood taunts Wallach by literally leaving him hanging and riding away as Morricone yet again gives our eardrums symphonic bliss. It’s a wicked little epilogue that illustrates the character’s dry, subtle sense of humour nicely and I remember my dad (this was a favourite for him) rewinding it just to catch the beats a second or third time. The third is a moment where Eastwood comes across a soldier who is dying in the dust. He offers the man a drag off his cigarette, and the simple action suggests a beating heart and flickers of compassion in a mostly hard, stoic fellow. Nice touch.

-Nate Hill