Surely a seasoned connoisseur of the silver screen can relate the experience of watching a film to emotional responses which seem to transcend the medium all-together. For instance, certain films may have a distinctive smell; others might even allow one to taste something either delectable or truly putrid on the tip of their tongue. Robert Altman’s MCCABE AND MRS. MILLER, a whiskey-soaked indictment of American idealism filtered through the abstracted gaze of a hazy opium den, truly has the best of both worlds – the film smells strongly of musk and is bitter to the taste but nonetheless warm once it’s in you. It has the benefit of seamlessly evoking homeliness and absolute desolation in equal measures; not once is one allowed to truly sit back and take in the spectacle on a base level, but if that’s not somehow oddly ingenious in its own right, then I’ll be damned.

John McCabe (Warren Beaty) arrives in Presbyterian Church, Washington as a stranger, but soon establishes himself as a legend of his own distinct variety. A gambling man with a detrimental love affair with the bottle, McCabe is immediately met with suspicion on the part of the townspeople, who suspect he’s really a gunslinger that shot one of their own over a card game some time ago. Nevertheless, it’s his reputation – coupled with his intense personality – that allows McCabe to be seen as a leader among loners and losers in this quiet little Northwest town. It is here that he aspires to establish a brothel, the first step in doing so being the acquisition of three women from one of the neighboring towns.

This, of course, will hardly be substantial in the long run. Along comes another stranger, Constance Miller (Julie Christie), who proposes that the two become business partners. It’s an offer that McCabe simply can’t refuse, and they’re all the better for it; it’s not long before three girls turns into about a dozen and the establishment is doubling as a bathhouse. As rewarding as this venture appears to be, the attempted intervention on the part of a nearby mining company indicates there may be trouble ahead for both business and personal pleasure alike.

Only a select few films have a kind of palpable density that the viewer feels right in the gut, and as it turns out Altman has made quite a few of them. Throughout the course of just two hours, man himself is challenged (the tragedy of masculinity suppressing all which stands in its path), and everything – land and life alike – has a dollar value. For instance, when McCabe continually refuses the offers from the mining company’s shady representatives, they send over a trio of bounty hunters to seal the deal. Afraid for his life but unwilling to leave the town and business he helped start, McCabe turns to his lawyer for advice, but is instead treated to a spiel that basically amounts to the company’s safety being favored over McCabe’s. The poor bastard’s response is genuinely haunting: “Well I just, uh…didn’t want to get killed.”

This is a film that soars, perhaps even more-so than the average Western (MCCABE is revisionist). Altman’s uncanny genius can be traced back to his modesty, quite an appealing quality in any artist, though given the sense of scale and impeccable attention to detail present in his work it’s almost a bit amusing. And yet, even though there are moments of genuine humor, no doubt provided by McCabe himself, the character remains a tragic one; one whose deepest flaws would appear to be almost entirely of his own making. The man is an enigma and a half to the naked eye. And Mrs. Miller, who as it turns out has a bit of an opium habit, is essentially the product of an unnecessarily harsh world dominated by the opposite sex, a world in which her expertise doesn’t seem welcome. And thus, the romanticism of the genre is stripped from Altman’s warped worldview, and in its place a new kind of grandeur emerges.

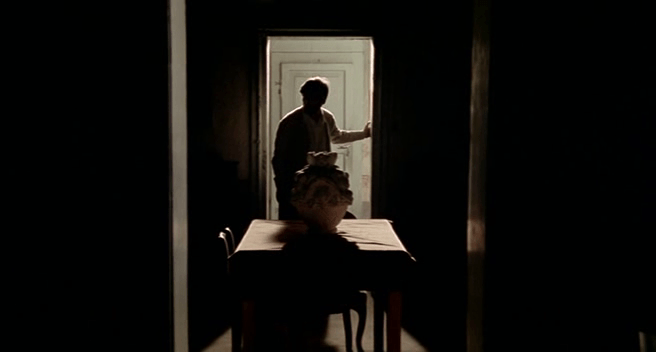

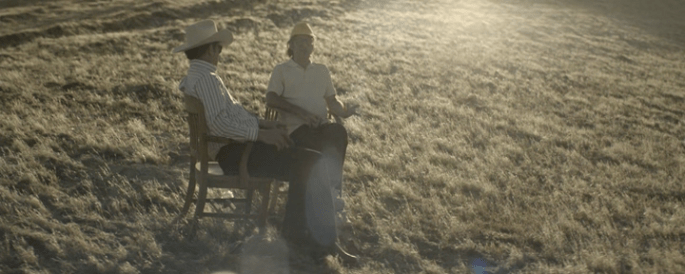

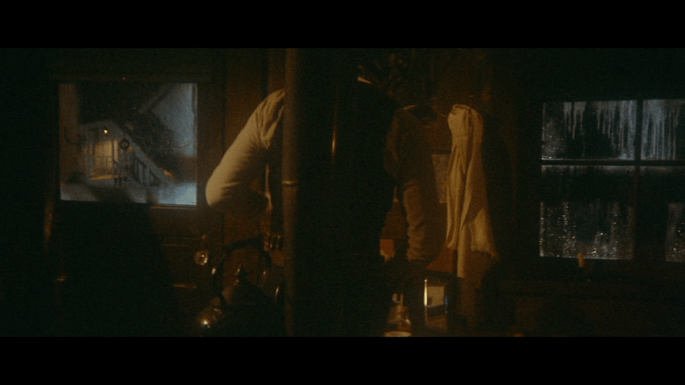

It goes without saying at this point, forty-something years after the fact, that Vilmos Zsigmond’s cinematography is absolutely note-perfect. The world in which the tortured, titular souls occupy is one largely confined to dark rooms and dusty bars; and the town’s exteriors couldn’t possibly be any rougher. There’s an inherent bleakness to it, and yet when there is any semblance of light shining bright at the end of the tunnel, it does not go unnoticed. Not only does this feel absolutely distinctive in terms of its genre, Altman and Zsigmond go the extra mile to find beauty in even the most deliberately obscured of images. Form is no longer so well-defined and the rules no longer apply in the same way that they used to.

Altman’s films tend to have rich, multi-dimensional soundscapes in which the abstraction of sonic perception gives way to a new language of its own. Here, no spoken word is free of the director’s unique grasp. Conversations are always overlapping to the point where the subject becomes more important to the viewer than the content, which is ultimately an effective method of conjuring up such an off-kilter atmosphere. Lou Lombardo’s editing is equally as inventive – time feels almost nonexistent in this town after we’ve spent a considerable amount of time there. The focus shifts between characters both integral to the central relationship and generally insignificant, adding to their collective mystique. Altman challenges us to embrace this very quality head-on, to return to a sort of exhilarating ambiguity that audiences of today have all but shunned.

The frontier unveils new angles from which to exquisitely immortalize it and the frontiersmen themselves remain largely the same. The cinema of transcendence is alive and well, drinking bourbon by the fireside, mumbling incoherently under its bearded breath. The lovely, brooding songs of Leonard Cohen allow it – and us – to drift off into a state of near unconsciousness; a state from which we’d hardly like to return. MCCABE AND MRS. MILLER is a subtly colossal achievement, especially in the positively brilliant final twenty minutes, a film of dreamy, universal resonance. It’s a world you could settle into for twice – perhaps even triple – the length we’re provided with. “I know that kind of man, it’s hard to hold the hand of anyone who is reaching for the sky just to surrender. And then sweeping up the jokers that he left behind, you find he did not leave you very much, not even laughter.”

![ouijagallery1-5769ed28e7f63-1[1].png](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ouijagallery1-5769ed28e7f63-11.png?w=685)

![Ouija-Origin-of-Evil-Photo-2[1].png](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ouija-origin-of-evil-photo-21.png?w=685)

![Ouija-Origin-of-Evil-5[1].jpg](https://podcastingthemsoftly.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/ouija-origin-of-evil-51.jpg?w=685)