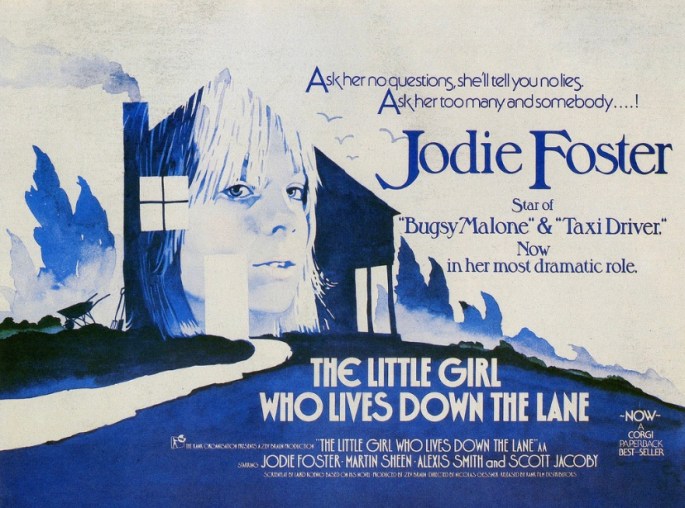

Jodie Foster had an interesting and edgy first leg of her career, with The Little Girl Who Lives Down The Lane being one of threw weirdest thrillers I’ve ever seen and certainly the strangest project shes been attached to that I’ve come across. Foster, age 13 or so here, plays Rynn, a girl living alone in a drafty house in a desolate Maine village that manages to be frightening and picturesque in the same stroke. The film doesn’t tell you right away why she’s alone but instead shows us a regular onslaught of visitors to her house who range from benign to eccentric to downright dangerous. Her landlady (Alexis Smith) is an overbearing bitch, the local police officer (Mort Shuman) is kind and compassionate and a teenage magician (Scott Jacoby) is someone she finds companionship and even romance with. The real trouble is in Martin Sheens violent, creepy sex offender who has a habit of showing up while she’s alone and getting real rapey on her. So who is this girl, and who thought up such a bizarre, unwieldy concept for a film? Well, as illogical, clunky and tasteless as I can’t be, I still found it pretty compelling, for Foster’s ethereal performance, for the sheer lunacy of its central premise, and I appreciated it in a sort of ‘dream logic meets modern fairytale’ way, which I’m not sure if the filmmakers were going for instead of a straightforward horror/thriller approach (it doesn’t work at all from that angle) but let’s just pretend that was their intention. Either way it’s a curio worth checking out simply for the audacity of the thing, and for Foster completists making their way through the cobwebs of her early career genre stuff. Also fun fact for David Lynch fans, the man directly references this film in his Twin Peaks: The Return and it’ll be fun for any avid Peaks fan to figure out why as they clamber through this narrative.

-Nate Hill