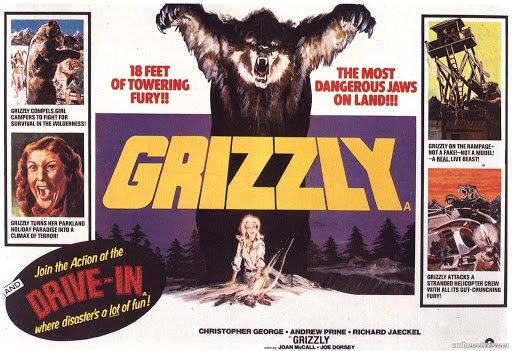

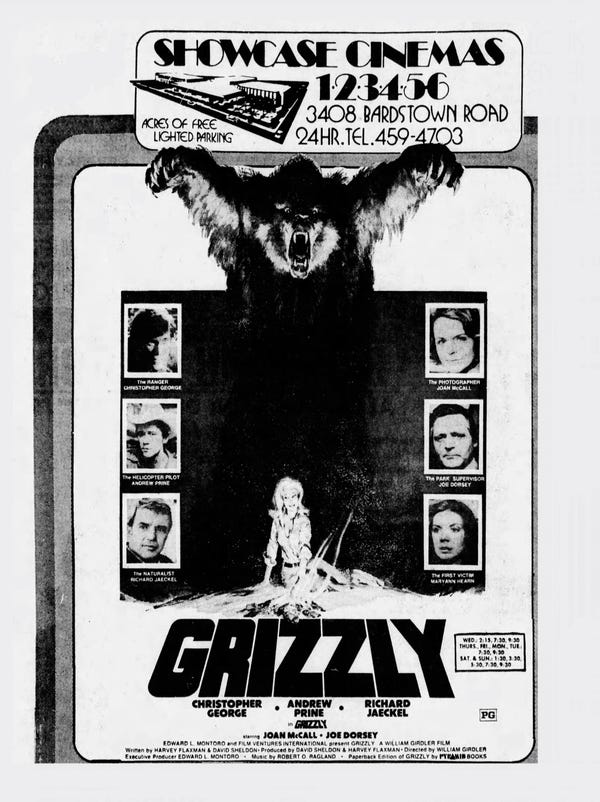

David Sheldon, who had been a producer for Bill Girdler starting on the Louisville-bound Combat Cops, AKA The Zebra Killer, AKA The Get Man, three whole films and two mere years before Grizzly — if that tells you anything about the furious productivity of Girdler and the dollar signs floating within his eye sockets — wrote a script with one-time Girdler alumni Harvey Flaxman, based on a terror-induced encounter with a bear on a camping trip Flaxman had taken with his family years prior. (Jaws also happened to have come out a few weeks before the two actually wrote the script… but I’m sure that had nothing at all to do with it… nothing at all.) Girdler, always looking for the next big money-maker, spotted the screenplay on Sheldon’s desk, read it, and nicely offered to help finance the beat-by-beat Jaws-in-the-woods extravaganza… on one major condition… he gets to direct the movie, of course.

Lee Jones, who had served as assistant director and production manager on Bill’s first local film, Asylum of Satan, and upgraded to producer on his second Kentucky-fried Psycho rehash, Three on a Meathook, helped Girdler find financing within a week’s time — and just as Warner Brothers themselves were about to reach out to Sheldon and Flaxman to make the movie, Bill and Lee quickly swept in with the financial backing of one Edward Montoro, an unstable former airline pilot from Cleveland whose air career had been cut short by a major plane crash, which he survived, and whose life was subsequently shifted and promoted to serve as Georgia’s Film Commission by then-Governor, Jimmy Carter. Montoro, now a sexploitation and b-horror maestro, backed the film independently with $750,000, locked everyone into production contracts, and eventually… took the money and ran, a pattern that arises all too often in the strange tale of Montoro’s film producing career.

Grizzly would become the highest grossing independent film of 1976, beating out even Monty Python and the Holy Grail in box office proceeds, but Montoro had bigger and better ideas. He kept all the profits to himself, leading Girdler and others to file suits against him. Despite being left destitute, living out of Leslie Nielsen’s guest house for a period of time after production, clearly Girdler had nothing against Montoro, seeing as he’d come back as producer on Day of the Animals the following year. But Montoro’s saga in Bill’s life would end there and carry on into bizarre, obscure legend. Grizzly wasn’t the last Jaws rip-off Montoro would make. He was sued by Universal Pictures in 1981 over The Last Shark and, after a string of unsuccessful b-movies in the early 80’s, truly nothing is known about Montoro or his whereabouts after the year 1984 when he mysteriously vanished, never to be seen again, with the millions of dollars he had stolen from the account books of his production company, FVI, which would end up bankrupted less than a year later.

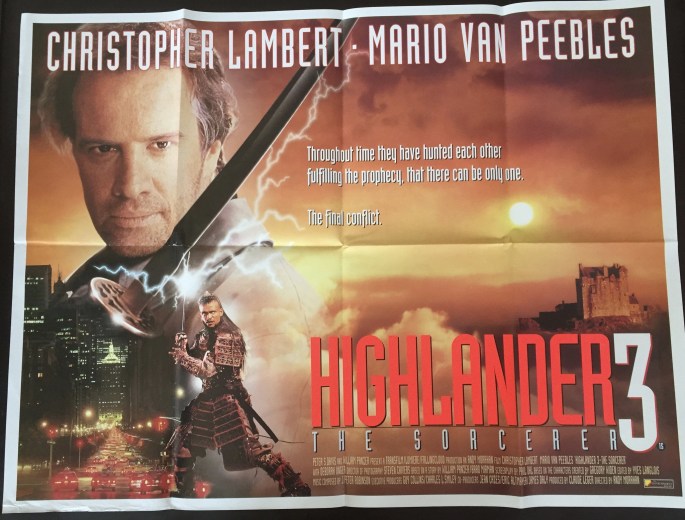

The film itself that ended up being cobbled together by these lunatic men is indeed a blast. A campfire gorefest that follows the exploits of the most frustrated, cynical department of park rangers you’ll ever meet as they try to halt a murderous bear and wage battle with the state officials who refuse to close the park down. To call it campy would be too puntastic and on-the-nose, but it’s the only valid description. Promotional materials say the bear is 18-feet tall, the characters say the bear is 15-feet, and reality says the bear — Teddy, as he was known on set — was 11-feet, close to hibernation, irate and prone to bursts of anger. Oh, and did I mention the bear was mostly untrained and the cast had to stay far away from him? That’s about right.

Meanwhile, Girdler directs with a certain accelerated type of gravitas when compared to his previous films. This is very much a case of Billy Goes to Hollywood. The gore sequences have a fun, lean, mean-spirited, European flavor to their jarring nature. Girdler gives us the flip-side of the Spielbergian experience. We don’t watch Jaws and cheer on Bruce the Shark. We genuinely care for Brody, his family, his men, and even the townsfolk like the Kintners and Ben Gardner. That’s because Spielberg is the ultimate empathy artist. But Bill Girdler? He’ll make you cheer on the bear. Whether it’s punching its way through the roof of a house, swiping the camera with its furry claws matted in blood, or mauling a poor, innocent child to death in purely horrific fashion — you just can’t help but clap your hands together and howl to the heavens.

There’s an ironic, authentic heartbeat to the madness here, just like in every other cheap Girdler film, but it’s manifest in a different way than Spielberg’s type of heart. You can feel the sterling ingenuity, the love of making films, and a locally-born fervor at every turn. (And keep your eyes peeled, by the way, for Louisville’s own late, great Charlie Kissinger, Girdler veteran and Fright Night “Shock Theater” host, the Fearmonger himself, as the doctor after the initial bear attack.) Girdler’s empathy was always rooted in money — which he definitely didn’t have after the revenue of this sleeper hit was stolen from him — but he was smart and knew that even if you were to rip-off all the bigger-budget films in the world, you wouldn’t make any money unless you won the audience on to your side. Or, in this case, the grizzly’s side…

Grizzly is now available on Blu-Ray from Severin Films, including a behind-the-scenes documentary entitled Movie Making in the Wilderness offering the rare opportunity to see Girdler working on-set. Order it here.

______

Tyler Harris is a film critic, English teacher, and former theater manager from Louisville, Kentucky. His passionate love for cinema keeps him in tune with his writing.