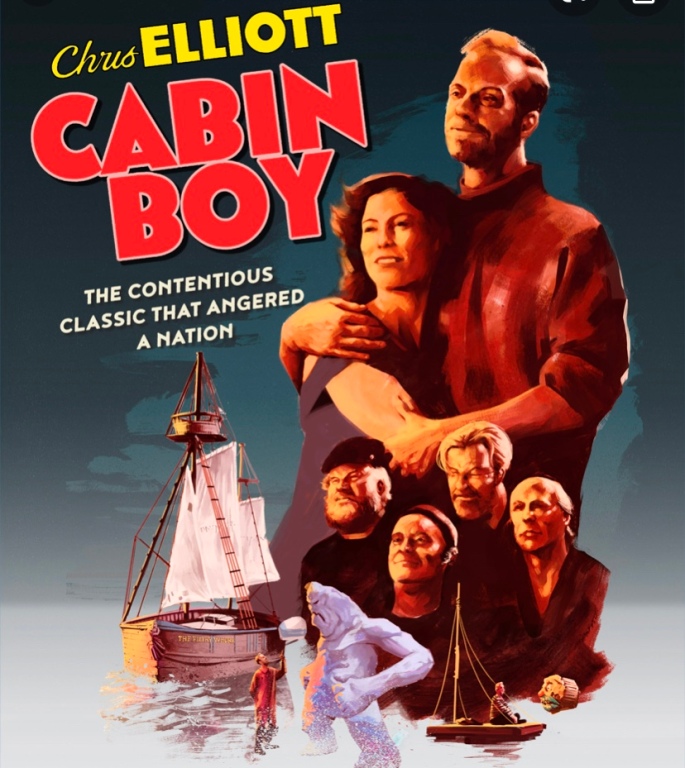

I’ve always kind of known Cabin Boy existed, but I’ve skirted around it for years because.. well, as funny as that Chris Elliott guy is in other stuff (he’s the best part about Scary Movie 2) I just didn’t think he could carry an entire comedy on his own, and the thing just looked stupid based on the DVD cover. Well the good news is that he doesn’t have to carry the whole thing on his own because this thing is so packed with character actors, super random cameos, bizarre practical effects, trippy vignettes and eccentric humour it carries itself on sheer outlandish momentum alone. I also wasn’t prepared for how fucking weirdly surreal and unearthly much of it is, it in fact might be one of the strangest films I’ve ever seen and in that regard it succeeds on sheer cult status merit alone. Elliott is pretty idiotic as a self proclaimed “fancylad” (they pronounce it as one word), a rich, spoiled little asshole who leaves his cushy life to run his father’s business in Hawaii but accidentally boards a salty fishing vessel after being given wrong given directions by David Letterman (I’m not making that up). The crew of this boat is populated by the grizzled likes of James Gammon, Brion James, Brian Doyle Murray, Ritch Brinkley (the obnoxious county prosecutor from Twin Peaks, for anyone as nerdy as me who remembers) and a young Andy Richter. They don’t take kindly to Elliott’s snooty attitude though and basically make him the Boat’s Bitch until he can earn his stripes. The film is terminally dumb in many areas but sometimes the script really surprised me with hilariously subtle comedic dialogue and deftly hysterical performances from the main cast and cameos alike. The central plot at some point gives way to a jaw dropping, delirious bout of random interludes including an iceberg monster, a Norwegian half man/half shark creature called Chocki (Russ Tamblyn, of all people), a pissed off Olympic swimmer (Melora Walters), a floating cupcake (Jim Cummings), a cave dwelling Kama Sutra goddess (Ann Magnuson) and in the film’s funniest bit, her Brooklyn born giant of a husband (Mike Starr, always love this guy) who tries to open a hardware store for seagulls. It’s about as fucking off the wall as it gets and suffice to say I was not prepared for the brand of deranged lunacy this film has to offer but I quite enjoyed a good portion of it. In a world where the comedy genre is so saturated with uninspired, limp-dick efforts and terminal misfires, I appreciate something with the verve, lack of inhibitions and capacity for abstract thought that lets it all hang out and throws every certifiably insane idea at the wall to see what sticks. Most of it does.

-Nate Hill