Until recently, most adaptations of independent comic books were far more successful (and by successful I mean faithful to their source material) than long-running mainstream ones from the two largest comic book companies, Marvel and DC. One only has to look at examples, such as Ghost World (2001), American Splendor (2003) and Hellboy (2004) against the failures of Catwoman (2004), Elektra (2004) and Constantine (2005). So, why are the first three films more satisfying triumphs and the last three empty exercises in style? The answer is simple. In the case of the first three movies, the filmmakers wisely allowed the comic book creators direct involvement in the filmmaking process, whether it was working on the screenplay (as with Ghost World and Hellboy) or actually appearing in the movie (American Splendor).

In the past, the comic book creator was, at best, a peripheral presence in the filmmaking process, or not even included at all. With bigger, longer running series, like Spider-Man or Superman, it is much harder to include the creator because there is not just one but many who have worked on the comic book over the years. Where does the filmmaker even start in these cases? To be fair, with Iron Man (2008) began a great run of adaptations of Marvel Comics being successfully translated to the big screen but before it the examples were few and far between.

It only makes sense that if one is going to adapt a comic book into a film that it be faithful in look and tone to its source material. Otherwise, why adapt it in the first place? Of course, there is always the danger of being too faithful to the look of the comic and not being faithful to its content (characterization, story, dialogue, etc.) like Warren Beatty’s take on Dick Tracy (1990) — all style and no substance. It goes without saying that the next logical step would be to include its creator, if possible, in the process so as to achieve the authenticity and integrity of the source material. Filmmaker Robert Rodriguez took this notion to the next level with Sin City (2005) by having its creator Frank Miller co-direct the movie with him. In fact, Rodriguez is so respectful of Miller’s work that he not only has the artist’s name listed first in the directorial credit but also displays his name prominently above the film’s title.

Sin City began as a series of graphic novels created by Miller. They are loving homages to the gritty pulp novels Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane and classic film noirs from the 1940s and 1950s. Miller’s world — the dangerous, crime-infested Basin City — is populated by tough, down-on-their-luck losers who risk it all to save impossibly voluptuous women from corrupt cops and venal men in positions of power through extremely violently means in the hopes of ultimately redeeming themselves. The movie ambitiously consists of three Sin City stories: That Yellow Bastard, The Hard Goodbye, and The Big Fat Kill with the short story, “The Customer is Always Right” acting as a prologue.

In the first story, Hartigan (Bruce Willis), a burnt-out cop with a bum-ticker and on the eve of retirement, is betrayed by his partner (Michael Madsen) after maiming a vicious serial killer (Nick Stahl) of young girls who also happens to be the son of the very power Senator Roark (Powers Boothe). The next tale features a monstrous lug named Marv (Mickey Rourke) who wakes up in bed with a dead prostitute named Goldie (Jaime King) and decides to get revenge on those responsible for killing the only thing that mattered in his miserable life. The final segment focuses on Dwight’s (Clive Owen) attempt to keep the peace in Old City when the prostitutes who run the area unknowingly kill a high profile (and also a sleaze bag) cop named Jack Rafferty (Benicio del Toro) and in the process risk destroying the precarious truce between the cops and the hookers that currently exists.

The three main protagonists are all well cast. Bruce Willis is just the right age to play Hartigan. With the age lines and the graying stubble on his face, he looks the part of a grizzled, world-weary cop with nothing left to lose. Willis has played this role often but never to such an extreme as in this film. Quite simply, Mickey Rourke was born to play Marv. With his own now legendary real life troubles and self-destructive behavior well documented, the veteran actor slips effortlessly into his role as the not-too-bright but with a big heart hero. British thespian Clive Owen is a pleasant surprise as Dwight and is more than capable of convincingly delivering the comic’s tough guy dialogue. As he proved with the underrated I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (2003), Owen is able to project an intense, fearsome presence.

The larger-than-life villains are also perfectly cast. Nick Stahl exudes deranged sleaze as Roark, Jr. and cranks it up an even scarier notch or two once he undergoes his “transformation” as the Yellow Bastard of his story. Perhaps one of the biggest revelations is the casting of Elijah Wood as the mute cannibal Kevin. Nothing he has done previously will prepare you for the absolutely unsettling creepiness of his character. Finally, Benicio del Toro delivers just the right amount reptilian charm as Jackie-Boy. Not even death stops him from tormenting Dwight and it is obvious that Del Toro is having a blast with this grotesque character.

Miller’s pulp-noir dialogue may seem archaic and silly but it is actually simultaneously paying homage and poking fun at the terse, purple prose of classic noirs and crime novels of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Rourke, Willis and Owen fair the best with this stylized dialogue as they manage to sell it with absolute conviction. It helps that both Rourke and Willis have voices perfectly suited for this kind of material: weathered and worn like they have smoked millions of cigarettes and downed gallons of alcohol over the years.

Of the women in the cast, Jessica Alba is the only real miscast actress. Not only does she not look like her character, Nancy Callahan (who was much more curvy, full-bodied and naked most of the time in the comic) but she does not go all the way with the role and her line readings feel forced and unnatural. Fortunately, Rosario Dawson more than makes up for Alba as Gail, an S&M-clad, heavily-armed prostitute who helps Dwight dispose of Rafferty’s body. She looks the part and inhabits her role with the kind of conviction that Alba lacks.

Finally, somebody has realized that the panels of a comic book are perfect storyboards for a movie adaptation. With Miller’s guidance, Robert Rodriguez has uncannily recreated, in some cases, panel-for-panel, Sin City onto film. He has not only preserved the stylized black and white world with the occasional splash of color from Miller’s comic, but also the gritty, dime-novel love stories that beat at its heart. Fans of the comic will be happy to know that virtually all of the film’s dialogue (including the hard-boiled voiceovers) has been lifted verbatim from the stories and the sometimes gruesome ultraviolence has survived the MPAA intact.

If you think about it, Rodriguez’s career has led him up to this point. With the stylized, over-the-top action of Desperado (1995), the pulp-horror pastiche of From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) and the mock-epic Once Upon a Time in Mexico (2003), he has been making comic book-esque movies throughout his career. It was only a matter of time before he adapted an existing one. Cutting his teeth on these action movies has allowed him to perfectly capture the kinetic action of Miller’s comic. Seeing hapless thugs fly through the air at the hands of El Mariachi’s deadly weapons in Desperado foreshadows the cops being propelled through the air when Marv makes his escape in Sin City.

What Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) did for the pulp serials of the 1930s and ‘40s, Sin City does for film noir. There is no question that Sin City resides at the opposite end of the spectrum from Sky Captain. While both feature retro-obsessed CGI-generated worlds, the former looks grungy and lived-in and the latter is pristine and perfect-looking. Sin City is absolutely drenched in the genre’s iconography: hired killers, femme fatales that populate dirty, dangerous city streets on rainy nights. It is the pulp-noir offspring of James Ellroy and Sam Fuller with a splash EC Comics gore. Ultimately, Sin City is a silly and cool ride and one has to admire a studio for having the balls to release a major motion picture done predominantly in black and white with the kind of eccentric characters, crazed violence and specifically-stylized world that screams instant-cult film.

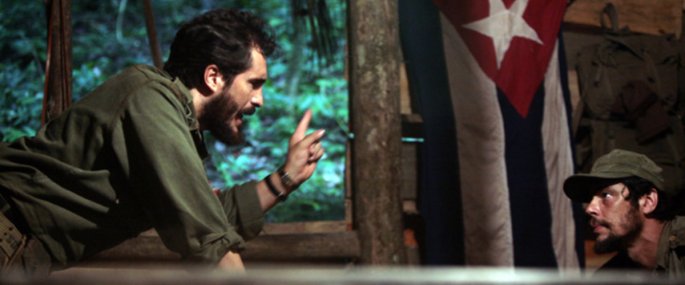

Che is ultimately a study in contrasts. What worked in Cuba did not work in Bolivia. Soderbergh’s film illustrates the differences. In Cuba, the revolutionaries were able to get the trust and support of the peasants while in Bolivia they feared the rebels. It must also be said that Castro played a key role in the success of the Cuban revolution and his absence in Bolivia, the galvanizing effect he had, is sorely missed. With Che, Soderbergh has created an unusual biopic that does its best to not try and manipulate you into feeling one way or another about the revolutionary. Instead, it shows two very different examples of the man’s philosophies put into practice and how they played out – one a success and the other a failure. Che was a polarizing historical figure long before this film came along and will continue to be long afterwards.

Che is ultimately a study in contrasts. What worked in Cuba did not work in Bolivia. Soderbergh’s film illustrates the differences. In Cuba, the revolutionaries were able to get the trust and support of the peasants while in Bolivia they feared the rebels. It must also be said that Castro played a key role in the success of the Cuban revolution and his absence in Bolivia, the galvanizing effect he had, is sorely missed. With Che, Soderbergh has created an unusual biopic that does its best to not try and manipulate you into feeling one way or another about the revolutionary. Instead, it shows two very different examples of the man’s philosophies put into practice and how they played out – one a success and the other a failure. Che was a polarizing historical figure long before this film came along and will continue to be long afterwards.