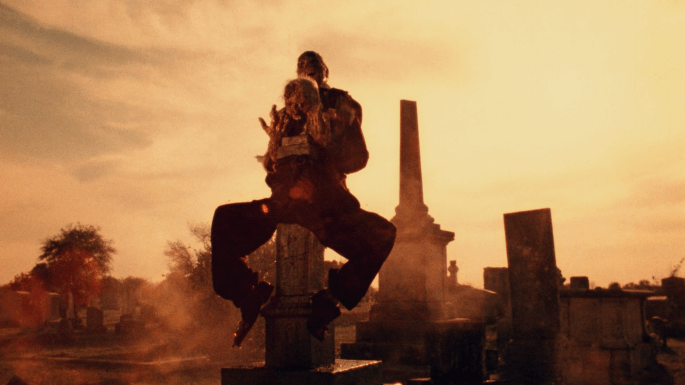

In the opening seconds of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, Russ Meyer marries sex and violence by employing a stern narration that explicitly welds the two together over the visual of the ever multiplying, squiggly optical soundtrack that quickly fills the frame like a hostile takeover. The narration warns the audience that you’ll never know where that mix of pleasure and pain will turn up but that, among other locations, it COULD happen in a go-go club.

And that’s absolutely goddamn right because the go-go club in question is the place of vocation for Varla (Tura Santana), Rosie (Haji), and Billie (Lori Williams), a group of pneumatic, ass-kicking thrill seekers who roam the edges of the California desert and look for kicks in a manner so cavalier that they might as well be going antiquing. If this sounds a little familiar it’s because it is as Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! is basically Motorpsycho! but with females in hot rods instead of dudes on bikes. But the question isn’t whether this is a copy job or not. Hell, even Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Alfred Hitchcock explicitly remade their own pictures. The question is whether or not the formula is bettered by the update. And, like the celluloid equivalent of Ms. Pac Man, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! is a marked improvement on an already enjoyable foundation.

There’s a bit more to Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! than there was to Motorpsycho! as Varla and company not only find lethal kicks in the California wasteland in the guise of Tommy (Ray Barlow) and Linda (Sue Bernard), two all-American kids who run afoul of the group. They also find a crippled degenerate (Stuart Lancaster) who lives on a piece of dusty property, lording over a hunk of money he received after a railroad accident. His heart twisted with misanthropy and misogyny, he is assisted by his hulking, simpleminded son known as The Vegetable (Dennis Busch) and Kirk (Paul Trinka), his more sophisticated, well-read, and saner progeny. All of these combustible elements explode in the final reel as the film tacks close to Meyer’s precedence of directing ultra violent climaxes, delivering on the promise in the opening narration and then some.

Though Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! was a financial failure and ended Meyer’s gothic period (and, sadly, was also the last film he shot in black and white), saying time has been kind to it would be a grand understatement. While the financial success of Motorpsycho! was the impetus for making Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, who the hell even talks about Motorpsycho! these days except for Meyer fanatics? Conversely, the image of the trio of Varla, Rosie, and Billie emblazons the front of many a t-shirt and poster and their cinematic legacy seeps into the DNA characters running all the way up to and beyond Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof from 2007.

Wasp-waisted, Porsche-driving Tura Santana reigns supreme as the black souled Varla, an amoral animal who doesn’t much deliver her dialogue as she does whip it. She’s equal parts turn on and terror as a high-octane, hedonistic creature that swings every which way as long as it’s pushing the envelope of getting her rocks off. “Whatever you want,” she purrs to the man she’s seducing out of his fortune, “I’m your cup to fill.” Wielding dictatorial control of the group, Varla turns on everyone who displeases her whether they are friend or foe. When Billie breaks free of the caravan and decides to go for a swim all by her lonesome, she gets beaten for the infraction by Rosie at Varla’s command, the latter leering at the two of them as they wrestle in a wet and sandy tangle. She assets dominance in a dangerous and impromptu game of chicken with her two friends across the salt flats and when she is later in danger of losing a timed race against a mid-level square, she simply runs him off the track, beats him to death, and kidnaps his bubble-headed girlfriend. Varla is simply not to be fucked with. As she snarls “I never try anything. I just do it. I don’t beat clocks, just people,” she sounds more like the Jedi school teacher I’d rather have than that dull-ass Yoda.

By contrast, Rosie is tough as leather but still has something of a tender heart when it comes to her feelings for Varla evidenced by the sad jealousy that masks her face as Varla rolls in the hay with a mark showing a knowingly bitter and heart-sinking ring of truth to it. And Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! was, in fact, the first of Meyer’s films to introduce lesbian relationships into his ever-expanding encyclopedia of sexual progress that was as sociological as it was personal. And even though he didn’t craft the most positive role model on the planet, the bisexual Varla has since become a symbol of tough, feminine independence and her plain-spoken, unvarnished honesty is admirable even if it would be a total HR nightmare in any other world.

But even though she’s soft for Varla, Rosie is anything but everywhere else. As played by the amazing Haji, Rosie’s ersatz, overblown “shutta up your mouth” accent is 15/10 hilarious and she gets one of the greatest lines of the film when she speaks incredulously at the mention of a soft drink by ensuring Linda understands that Rosie and the gals “don’t like nothin’ a-soft.” The rest of the cast, most especially Lori Williams and Meyer stalwart Stuart Lancaster, deliver their performances with gusto, spitting each bit of astonishing dialogue with glee and slowly elevating everything until its fever pitch climax which earns its feminist praise by giving even its weakest character the most satisfying deliverance.

Russ directs, edits, co-produces, and gets story credit for Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, but the absolutely incredible screenplay was written by Jack Moran, one-time child actor who popped up as the prospector/narrator in Meyer’s Wild Gals of the Naked West and would go on to appear in Common Law Cabin along with penning the deliciously quotable Good Morning and Goodbye and Finders Keepers…Lovers Weepers, ranking Moran only second to Roger Ebert as Meyer’s greatest third-party scribbler. And in keeping uniform with Meyer’s usual compositions, Walter Schenk’s amazing camerawork is kept at tits and ass level but always on the uptilt to exude the strength of the characters while putting a big bright spotlight on their physical attributes (especially in the case of Varla and Rosie). In a lot of ways, this is still a roughie but, quite unusually, the women are the ones to inflict almost all of the violence. And, like Motorpsycho!, this is the rare Meyer film that contains no nudity.

Capped off with the awesome title tune by the Bostweeds, Faster, Pussycat! Kill Kill! was a breakthrough for Meyer even if if didn’t seem like it at the time. This was mostly evident as he entered his soap opera phase with lead women who were still randy, ribald, and ready for action but a little more demur than the nihilistic Varla and who are trapped in worlds and circumstances she’d simply karate her way out of. Varla was the first of the Meyer heroines of whom it was asked if she were woman or animal and perhaps the public just wasn’t ready for it at the time. But Meyer would work his courage up to grace the screen with another in just three years time and, at that time, they’d be ready. Boy, would they EVER…

(C) Copyright 2021, Patrick Crain