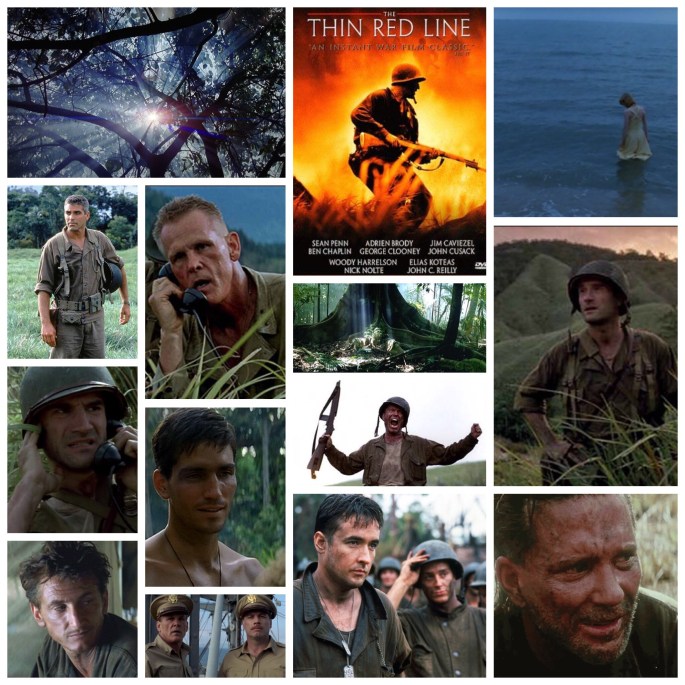

There’s a scene in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill 2 where Michael Madsen’s Budd lays down the sword rhetoric: “If you’re gonna compared a sword made by Hattori Hanzo, you compare it to every other sword ever made, that wasn’t made by Hattori Hanzo.” I’d like to augment that slightly in the case of Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line and say, “If you’re gonna compare The Thin Red Line, you compare it to every other war movie ever made that *isn’t* The Thin Red Line.” That’s not to say its better than all the rest or on any kind of quality pedestal, it’s just simply unlike every other war film out there, and that differentiation makes it an incredibly special picture. Why, you ask? Because it takes a ponderous, meditative approach to a very hectic horrific period in history, and takes the time to explore the effects of conflict on both humanity and nature, as well as how all those forces go hand in hand. What other war film does that? Malick uses a poets eye and a lyricist’s approach to show the Guadalcanal siege, a horrific battle in which lives were lost on both sides and the countryside ravaged by the fires of war. To say that this film is an ensemble piece would be an understatement; practically all of Hollywood and their mother have parts in this, from the front and centre players right down to cameos and even a few appearances that never made it into the final cut (which I’m still bitter about). The two central performances come from Jim Caviesel and Sean Penn as Pvt. Welsh and Sgt. Witt. Welsh is a compassionate, thoughtful man who seems primally uncomfortable in a soldiers uniform, and shirks the materialistic horror and industrialist grind of war to seek something more esoteric, a reason for being amongst the horror. Witt is a hard, cold man who sees no spiritual light at the end of the tunnel and does his job with grim resolve, scarcely pausing to contemplate anything but the next plan of action. These two are archetypes, different forces that play in each of us and, variations of which, are how we deal with something as incomparable as a world war. Around them swirl an endless sea of famous faces and other characters doing the best they can in the chaos, or simply getting lost in it. Nick Nolte as a gloomy Colonel displays fire and brimstone externally, but his inner monologue (a constant with Malick) shows us a roiling torment. A captain under his command (Elias Koteas) has an emotional crisis and disobeys orders to send his men to their death when thunderously pressured by Nolte. Koteas vividly shows us the heartbreak and confusion of a man who is ready to break, and gives arguably the best performance of the film. Woody Harrelson accidentally blows a chunk of his ass off with a grenade, John Cusack climbs the military rank with his tactics, John Savage wanders around in a daze as a sadly shell shocked soldier, Ben Chaplin pines for his lost love (Miranda Otto) and the jaw dropping supporting cast includes (deep breath now) Jared Leto, Nick Stahl, Tim Blake Nelson, Thomas Jane, Dash Mihok, Michael Mcgrady, John C. Reilly, Adrien Brody, Mark Boone Jr, Don Harvey, Arie Verveen, Donal Logue, John Travolta and a brief George Clooney. There’s a whole bunch who were inexplicably cut from scenes too including Bill Pullman, Gary Oldman and Mickey Rourke. Rourke’s scene can be found, in pieces, on YouTube and it’s worth a search to see him play a haunted sniper. Hans Zimmer doles out musical genius as usual, with a mournfully angelic score that laments the process of war, particularly in scenes where Caviesel connects with the natives in the region, as well as a soul shattering ambush on the Japanese encampment that is not a sequence that ten year old Nate has been able to forget since I saw it and the hairs on my neck stood up. This is a diversion from most war films; Malick always has a dreamy filter over every story he weaves: exposition is scant, atmosphere matters above all else and the forces of music and visual direction almost always supersede dialogue, excepting inner thoughts from the characters. If you take that very specific yet loose and ethereal aesthetic and plug it into the machinations of a war picture, the result is as disturbing as it is breathtakingly beautiful, because you are seeing these events through a lens not usually brandished in the genre, and the consequences of war seem somehow more urgent and cataclysmic. Malick knows this, and keeps that tempo up for the entire near three hour runtime, giving us nothing short of a classic.

-Nate Hill