Nicolas Winding Refn’s Bronson is based on the violent true life exploits of Britain’s famed criminal Charles Bronson, jailed for decades on purpose and loving it. These type of films usually have a dutiful, glossy biopic mechanism to them, but Refn is ever the extreme stylistic boundary pusher and the way he directs seems as if we’re actually in the hectic subconscious of the protagonist as opposed to looking in from the outside. It’s hazy, hallucinatory, weird, unpredictable and soaked in the feverish neon that has become the Danish maverick’s calling card. Then there’s the performance by Tom Hardy, which defies both description and classification. He doesn’t so much act as he does exist, like an element or a primal instinct, playing Bronson filled to the brim with cheeky aggression, animalistic behaviour, a galaxy of idiosyncratic mannerisms and the likability to keep us entranced through what, upon reflection, is actually a really fucked up and disturbing story. Bronson, born Michael Petersen, was busted barely out of his teens for terrifically botching an attempted post office robbery, chucked in the pen where he’d have been out in four years or so with ‘good behaviour.’ Well. Let’s just say that the good behaviour part isn’t in either his nature or his plan. He loves conflict, fights the guards any chance he gets, incites riots and makes life hell for the British correctional force. That’s basically the film, but the straightforward story only exists to serve a surreal tapestry of episodic, atmospheric interludes where the plot isn’t so much unfolding in a literate manner as it is taking a backseat to Bronson’s unconventional, self aware telling of his own story. There’s editing and colour timing that’s so saturated, so bizarre and out there you feel like the whole thing exists as a dream, resplendent with oddball character interactions, delirious, thumping soundtrack choices and the kind of mood-scape that sucks you right the fuck in. Refn doesn’t try and provide any answers to the psychological nature of a guy like Charles either, and that’s a wise move. It’s interesting to look at the third act in which his behaviour seems to take a turn for the better with the arrival of a helpful shrink/mentor only to have him gleefully fake everyone out and start causing shit again. It’s seemingly arbitrary and his antics don’t hand a purpose, frankly outlined by Refn as storyteller, and not historian. It’s about Charles, and this is *his* story, told by this whipped up, warped version of himself that’s personified by Hardy in what can arguably be called the performance that put him on the map, and whatever your gut reaction to a piece of cinema this provocative and strange, there’s no debate over what a galvanizing, brilliantly concocted sensory experience it is.

-Nate Hill

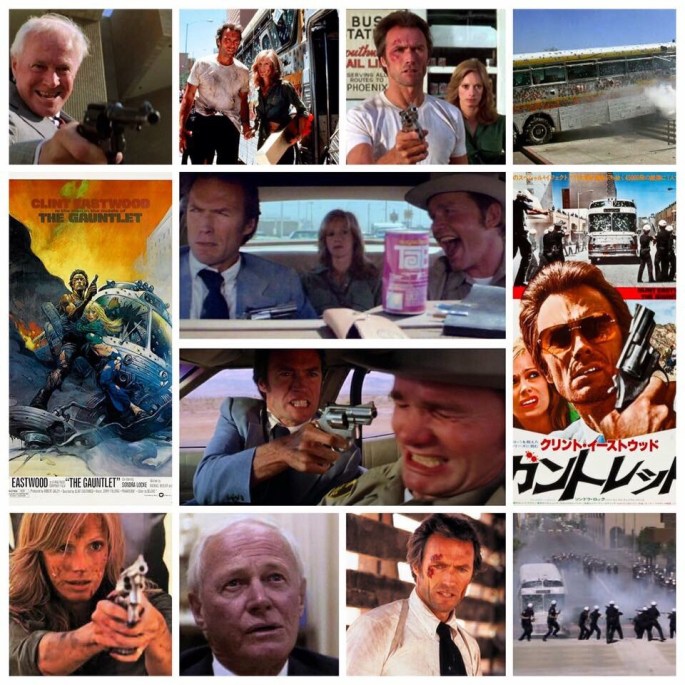

I love scrappy little cop flicks like Clint Eastwood’s The Gauntlet, a short, trashy exercise in exploitation that’s not only a departure from the heady, cerebral detective flicks he does but also miles off of the focused, gritty machismo of the Dirty Harry films. This is a low rent B movie and is proud of it, which is a rare commodity in Eastwood land. Boasting a terminally silly plot, lovably incapable protagonist and more bullets fired than all three Matrix movies stacked together, it’s a great way to spend a Saturday night when you have a hankering for old school action. Eastwood is Ben Shockley here, a disheveled mess of a Phoenix cop, heavily on the sauce and in no mood for the mission his uptight commissioner (William Prince, needing a moustache to twirl in his portrait of unapologetic evil) dispatches him on. He’s to escort a troublesome hooker (Sondra Locke) from Vegas back to Arizona where she will testify at a high profile mob trial. Of course every bent cop and his mother is on their trail, they can’t trust anyone in law enforcement and they’re on their own, forced to run a gauntlet of gunfire and corruption to bring her in. There’s three very odd, very hilarious set pieces that involve gunmen just fucking unloading clip after clip after clip in a way that the you might see on the Looney Toons, until the house they’re firing at *literally* falls apart. That’s the sort of slapdash style the film has, but it works in its dense specificity. Eastwood and Locke have chemistry, and it’s always cool to see the chicks in his action films have their own personality and impact on plot, not just part of the scenery or eye candy. Prince is so nefarious as the Commissioner that one wonders how a man like that ascended the ranks to that position, but in a film where’s he’s allowed to shut down a city block and order the *entire* Phoenix police force to empty boxes of bullets into an oncoming bus that Eastwood rolls up in, it isn’t that much of a stretch to believe. It’s just that kind of film, and I dug it a lot. Oh and look at that epic one sheet of a poster, whoever designed that should get a few medals. Great flick.

I love scrappy little cop flicks like Clint Eastwood’s The Gauntlet, a short, trashy exercise in exploitation that’s not only a departure from the heady, cerebral detective flicks he does but also miles off of the focused, gritty machismo of the Dirty Harry films. This is a low rent B movie and is proud of it, which is a rare commodity in Eastwood land. Boasting a terminally silly plot, lovably incapable protagonist and more bullets fired than all three Matrix movies stacked together, it’s a great way to spend a Saturday night when you have a hankering for old school action. Eastwood is Ben Shockley here, a disheveled mess of a Phoenix cop, heavily on the sauce and in no mood for the mission his uptight commissioner (William Prince, needing a moustache to twirl in his portrait of unapologetic evil) dispatches him on. He’s to escort a troublesome hooker (Sondra Locke) from Vegas back to Arizona where she will testify at a high profile mob trial. Of course every bent cop and his mother is on their trail, they can’t trust anyone in law enforcement and they’re on their own, forced to run a gauntlet of gunfire and corruption to bring her in. There’s three very odd, very hilarious set pieces that involve gunmen just fucking unloading clip after clip after clip in a way that the you might see on the Looney Toons, until the house they’re firing at *literally* falls apart. That’s the sort of slapdash style the film has, but it works in its dense specificity. Eastwood and Locke have chemistry, and it’s always cool to see the chicks in his action films have their own personality and impact on plot, not just part of the scenery or eye candy. Prince is so nefarious as the Commissioner that one wonders how a man like that ascended the ranks to that position, but in a film where’s he’s allowed to shut down a city block and order the *entire* Phoenix police force to empty boxes of bullets into an oncoming bus that Eastwood rolls up in, it isn’t that much of a stretch to believe. It’s just that kind of film, and I dug it a lot. Oh and look at that epic one sheet of a poster, whoever designed that should get a few medals. Great flick.