If Eggshells was Tobe Hooper’s way of showing Texas as a hospitable place where the entrenched past and the progressive future could find an uneasy truce in the name of peace, love, and harmony, then The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, his sophomore effort from 1974, aims to tear all of it down with shocking abandon. From the iconic opening flash shots of graves being desecrated to the tightly-wound, climactic ending, director Tobe Hooper and co-screenwriter Kim Henkel give the audience absolutely no breaks, immersing viewers in a cinematic world far beyond nature where exactly nothing is sacred.

In terms of plot, there may be no simpler film in the horror genre than The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Five young people travel to a dilapidated family homestead out in the wilds of rural Texas and fall victim to a neighboring backwoods clan of cannibal ex-slaughterhouse workers.

Gosh, it feels really stupid to reduce the film to just its structural elements because recounting the broad outline of the film is kind of like calling a Jaguar “a car”; you’re not technically lying but you’re vastly underselling the product to a stupid and irresponsible degree. Yeah, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is exactly as described and is more or less what you think you’ll be getting but it also achieves the absolute impossible by transcending the medium, establishing itself as a true nightmare printed on celluloid. It’s not that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a masterpiece of modern horror, it’s also that it’s the greatest horror film ever made and the clear victor in a race that’s not even particularly close. While Jaws did a number on people and shaped their attitudes about going to the beach, in reality there are only so many spots in the U.S. where a practical fear of sharks can really take hold. On the other hand, there are countless miles of country roads and rural highways dotted with the barest signs of civilization and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre roots itself in the mind in a way where each one of those dilapidated or barely functioning dwellings becomes suspect.

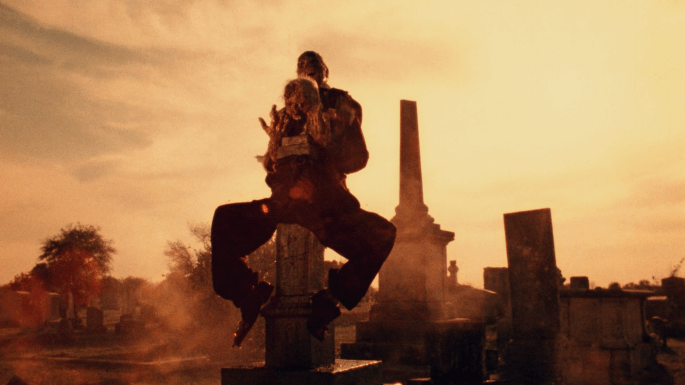

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre exists in a landscape where things are once close and a great distance; a place where time slips from day to night and back to morning in a sweaty compression. In Texas, the normal Jeffersonian survey grid that covers about 90% of the rest of the United States gives way to the weird, claptrap geometry of surveys and abstracts but this film exists in a land that feels even beyond that nonsense, landing somewhere totally uncharted. Geographically, it is a barren place where there is nowhere to turn when looking for solace or relief and where the characters are trapped between the two poles of a farmhouse and a gas station. There was a swimming hole that could once be found if you took the trail between two old sheds but it now leads to a dried out canyon of rocks and wild sunflowers. The only people who provide comfort and help are passers-through and absolutely are not native to the region. The only things on the radio are news reports about unspeakable horrors across the globe and twangy country music, all seemingly on a constant loop both day and night. Everything operates behind infinite curtains of unforgiving heat waves.

Conventions straight from gothic literature, specifically the examination of folks who untether themselves from society and live in a vacuum out in the middle of nowhere, are updated and amplified and contrasted with modernity in the guise of the post-Eggshells hippies in a van. We are forced to size up the primitive family with their more civilized counterparts and wonder why we get so much glee when Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) digs his chainsaw into the gullet of the whiny, needy, and disgusting Franklin (Paul A. Partain), invalid brother to final girl Sally (Marilyn Burns) who, in a Freudian move pulled off no less than two times, quite literally points three of his peers (Terri McMinn, William Vail, and Allen Danzinger) in the general direction of their doom as if he were being subsidized by Leatherface’s clan to do such a thing.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a film made up of memorable moments both great and small. Pam approaching the house as the camera tracks under the swing as it looms larger and larger like a giant that is about to swallow her whole; the corner of room packed with an animated, spindly nest of granddaddy long legs; the beautiful and darkly comic moment where the Old Man (Jim Siedow) confronts the Hitchhiker (Ed Neal) in the middle of the road, beautifully and macabrely backlit by the headlights of a pickup truck. One of the film’s greatest centerpieces, namely the introduction of Leatherface, is shocking and displays one of Hooper’s most favorite cinematic ideas (and one to which he would return time and time again) which is the unholy center of a world infested and rotten. As the set up is one big layered journey into hell and his initial appearance comes as a cold shock to the audience, Hooper parks it on the outer edge and plays the audience out to an unbearable level of discomfort, finally forcing the audience to simmer in the same paralyzed shock of Pam who sits dumbfounded among the detritus of bones both of animal and human origin after she literally stumbles onto same. Once orientated, Hooper springs the trap from the hell within the hell as Leatherface bursts out from behind the metal door, snatching Pam back into the house as she is trying to escape, her legs akimbo and lungs tearing themselves in half from her screams of terror that turn into screams of excruciating pain upon being unceremoniously hung on a meathook.

Employing a subjective camera that floats along the overgrown brush and looks out from the inside of roadside edifices as if something bigger and unseen is slowly deconstructing the known universe and all the logic and space that holds it together, Hooper and cinematographer Daniel Pearl set the audience on edge by hinting at something omnipresent that’s always observing even if the audience never actually sees it or knows what it is. Additionally, Hooper forces the audience to puzzle out just what exactly going on with the slaughterhouse family. Where every other Chainsaw film wears its cannibalism like a badge of honor bordered in bright neon, Hooper’s original keeps everything opaque with pieces of evidence floating about in a hazy, nightmarish rush that are never explicitly discussed but gel once one’s bearings are brought back center.

On a technical level, there is just nothing like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. While every other Chainsaw film has tried to recreate the ghoulish interior of the family house, none have even come anywhere close to achieving the kind of natural sense of a completely functional yet terrifying place as Robert Burns created and dressed it in 1974. In every other Chainsaw film, the house feels like a trapdoor-festooned dark ride developed by professional funhouse workers, completely inorganic and phony. The cinematography is nightmarish which seems pretty upside down given than half of the film takes place in the daytime but the palpable heat and humidity almost mixes with the 16mm color-reversal blowup to create something chemically upsetting to look at yet entirely alluring all at once. Hooper and Wayne Bell’s musique concrète score is jangling and knows how to create a forever disquieting sonic atmosphere and the sound design finds the most upsetting of tones and puts its foot on the gas. While the special effects are all great, John Dugan is under some aging makeup courtesy of W.E. Barnes that’s some of the best stuff I’ve seen this side of Dick Smith and can’t help but impress given the film’s budget.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a perfect film. It holds not one wasted shot, not one bum performance, and not one extraneous minute. Not one seam shows in its disorienting, maddening, uncomfortable, oppressive, and apocalyptic vision. There will never be another film like it nor will it ever find an equal. Tobe Hooper never came anywhere as close to hitting the heights as he does here but it really doesn’t matter as he could have directed nothing but industrial videos on 3/4” videotape for Honeywell for the rest of his life and gotten into director’s heaven and any and all halls of fame for just gestating The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. And that’s that.

(C) Copyright 2021, Patrick Crain