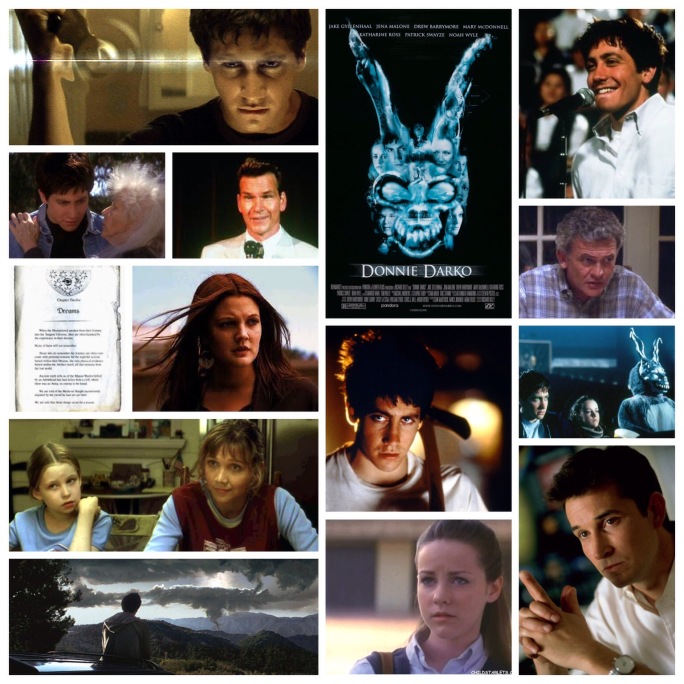

The director’s cut of Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had watching a film. It transports you to its many layered dimension with unforced ease and tells it’s story in chapters that feel both fluid and episodic in the same stroke. It has such unattainable truths to say with its story, events that feel simultaneously impossible to grasp yet seem to make sense intangibly, like the logic one finds within a dream. These qualities are probably what lead to such polarized, controversial reactions from the masses, and eventual yearning to dissect the hidden meaning which at the time of its release, didn’t yet have the blessing of the extended cut and it’s many changes. A whole lot of people hate this movie, and just as many are in love with it as I am. I think the hate is just frustration that has boiled over and caused those without the capacity for abstract thought to jump ship on the beautiful nightmare this one soaks you in. Movies that explore the mind, the unexplainable, and the unknowable are my bread and butter, with this one taking one of the premier spots in my heart. Kelly has spun dark magic here, which he has never been able to fully recreate elsewhere (The Box is haunting, if ultimately a dud, but his cacophonic mess Southland Tales really failed to resonate with me in the slightest). Jake Gyllenhaal shines in one of his earliest roles as Donnie, a severely disturbed young man suffering through adolescence in the 1980’s, which is bad enough on its own. He’s also got some dark metaphysical forces on his back. Or does he? Donnie has visions of an eerie humanoid rabbit named Frank (James Duval) who gives him self destructive commands and makes prophetic statements about the end of the world. His home life should be idyllic, if it weren’t for the black sheep he represents in their midst, displaying behaviour outside their comprehension. Holmes Osborne subtly walks away with every scene he’s in as his father, a blueprint of everyone’s dream dad right down to a sense of humour that shows he hasn’t himself lost his innocence. Mary McDonnell alternates between stern and sympathetic as his mother, and he has two sisters: smart ass Maggie Gyllenhaal (art imitating life!) and precocious young Daveigh Chase (also Lilo and Samara from The Ring, funnily enough). The film also shows us what a showstopper high school must have been in the 80’s, with a script so funny it stings, and attention paid to each character until we realize that none are under written, and each on feels like a fully rounded human being, despite showing signs of cliche. Drew Barrymore stirs things up as an unconventional English teacher, Beth Grant is the classic old school prude who is touting the teachings of a slick local motivational speaker (Patrick Swayze). The plot is a vague string of pearls held together by tone and atmosphere, as well as Donnie’s fractured psyche. Is he insane? Are there actually otherworldly forces at work? Probably both. It’s partly left up to the viewer to discern, but does have a concrete ending which suggests… well, a lot of things, most of which are too complex to go into here. Any understanding of the physics on display here starts with a willingness to surrender your emotions and subconscious to the auditory, visual blanket of disorientation that’s thrown over you. Just like for Donnie, sometimes our answers lies just outside what is taught and perceived, in a realm that has jumped the track and exists independently of reality and in a period of time wrapped in itself, like a snake eating it’s own tail. Sound like epic implications? They are, but for the fact that they’re rooted in several characters who live in a small and isolated community, contrasting macro with micro in ways that would give David Lynch goosebumps. None of this malarkey would feel complete without a little romanticism, especially when the protagonist is in high school. Jena Malone is his star crossed lover in an arc that finds them spending little time together, yet forming a bond that that feels transcendant. Soundtrack too must be noted, from an effective opener set to INXS’s Never Tear Us Apart to the single most affecting use of Gary Jules’s Mad World I’ve ever heard. It’s important that you see the director’s cut though, wherein you can find the most complete and well paced version of the story. There’s nothing quite like Donnie Darko, to the point where even I feel like my lengthy review is stuff and nonsense, and you just have to watch the thing and see to truly experience it.

Tag: Jake Gyllenhaal

Donnie Darko: A Review by Nate Hill

The director’s cut of Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had watching a film. It transports you to its many layered dimension with unforced ease and tells it’s story in chapters that feel both fluid and episodic in the same stroke. It has such unattainable truths to say with its story, events that feel simultaneously impossible to grasp yet seem to make sense intangibly, like the logic one finds within a dream. These qualities are probably what lead to such polarized, controversial reactions from the masses, and eventual yearning to dissect the hidden meaning which at the time of its release, didn’t yet have the blessing of the extended cut and it’s many changes. A whole lot of people hate this movie, and just as many are in love with it as I am. I think the hate is just frustration that has boiled over and caused those without the capacity for abstract thought to jump ship on the beautiful nightmare this one soaks you in. Movies that explore the mind, the unexplainable, and the unknowable are my bread and butter, with this one taking one of the premier spots in my heart. Kelly has spun dark magic here, which he has never been able to fully recreate elsewhere (The Box is haunting, if ultimately a dud, but his cacophonic mess Southland Tales really failed to resonate with me in the slightest). Jake Gyllenhaal shines in one of his earliest roles as Donnie, a severely disturbed young man suffering through adolescence in the 1980’s, which is bad enough on its own. He’s also got some dark metaphysical forces on his back. Or does he? Donnie has visions of an eerie humanoid rabbit named Frank (James Duval) who gives him self destructive commands and makes prophetic statements about the end of the world. His home life should be idyllic, if it weren’t for the black sheep he represents in their midst, displaying behaviour outside their comprehension. Holmes Osborne subtly walks away with every scene he’s in as his father, a blueprint of everyone’s dream dad right down to a sense of humour that shows he hasn’t himself lost his innocence. Mary McDonnell alternates between stern and sympathetic as his mother, and he has two sisters: smart ass Maggie Gyllenhaal (art imitating life!) and precocious young Daveigh Chase (also Lilo and Samara from The Ring, funnily enough). The film also shows us what a showstopper high school must have been in the 80’s, with a script so funny it stings, and attention paid to each character until we realize that none are under written, and each on feels like a fully rounded human being, despite showing signs of cliche. Drew Barrymore stirs things up as an unconventional English teacher, Beth Grant is the classic old school prude who is touting the teachings of a slick local motivational speaker (Patrick Swayze). The plot is a vague string of pearls held together by tone and atmosphere, as well as Donnie’s fractured psyche. Is he insane? Are there actually otherworldly forces at work? Probably both. It’s partly left up to the viewer to discern, but does have a concrete ending which suggests… well, a lot of things, most of which are too complex to go into here. Any understanding of the physics on display here starts with a willingness to surrender your emotions and subconscious to the auditory, visual blanket of disorientation that’s thrown over you. Just like for Donnie, sometimes our answers lies just outside what is taught and perceived, in a realm that has jumped the track and exists independently of reality and in a period of time wrapped in itself, like a snake eating it’s own tail. Sound like epic implications? They are, but for the fact that they’re rooted in several characters who live in a small and isolated community, contrasting macro with micro in ways that would give David Lynch goosebumps. None of this malarkey would feel complete without a little romanticism, especially when the protagonist is in high school. Jena Malone is his star crossed lover in an arc that finds them spending little time together, yet forming a bond that that feels transcendant. Soundtrack too must be noted, from an effective opener set to INXS’s Never Tear Us Apart to the single most affecting use of Gary Jules’s Mad World I’ve ever heard. It’s important that you see the director’s cut though, wherein you can find the most complete and well paced version of the story. There’s nothing quite like Donnie Darko, to the point where even I feel like my lengthy review is stuff and nonsense, and you just have to watch the thing and see to truly experience it.

David Fincher’s Zodiac: A Review by Nate Hill

David Fincher’s Zodiac is the finest film he has ever brought us, and one of the most gut churning documentations of a serial killer’s crimes ever put on celluloid. Fincher has no interest in fitting his narrative into the Hollywood box or sifting through the details of the real life crimes to remove anything that doesn’t follow established formula. He plumbs the vast case files and sticks rigidly to detail, clinging to ambiguity the whole way through and welcoming the eerie lack of resolution we arrive at with open arms. That kind of diligence to true life events is far more scary than any generic, assembly line plot turns twisted into stale shape by the writer (and studio breathing down their neck, no doubt). No, Fincher sticks to the chilling details religiously, starkly recreating every revelation in the Zodiac killer case with the kind of patience and second nature style of direction that leads to huge atmospheric payoff and a hovering sense of unease that continues to make the film as effective today as the day it was released. A massive troupe of actors are employed to portray the various cops, journalists, victims and pursuers involved with the killer during the 1970’s in San Francisco, the film unfolding in episodic form and giving each performer their due, right down to the juicy cameos and bit parts. Jake Gyllenhaal plays Rob Graysmith, a news reporter who becomes intrigued and eventually obsessed with the cryptic puzzles which the Zodiac taunts the bay area with by sending them in to the paper. Mark Ruffalo is Charlie Toschi, dogged police investigator who is consumed by the hunt. The third leg of the acting tripod is Robert Downey Jr as Paul Avery, another journalist who takes the failure in capturing the killer a little harder than those around him. The film dances eerily along a true crime path populated by many people who veered in and out of the killers path including talk show host Melvin Belli (a sly Brian Cox) , another intrepid cop (Anthony Edwards), his superior officer (Dermot Mulroney) and so many more. For such an expansive and complicated story it’s all rather easy to keep track if, mainly thanks to Fincher’s hypnotic and very concise direction, grabbing you like a noose, tightening and then letting you go just when you feel like you have some answers. While most of the film examines the analytical nature of the investigation, there are a few scenes which focus on the killings themselves and let me tell you they are some of the most hair raising stuff you will ever see. The horror comes from the trapped animal look in the victims eyes as they try rationalize the inevitability, with Fincher forcing you to accept the reality of such acts. One sequence set near a riverbank veers into nightmare mode. Every stab is felt by the viewer, every bit of empathy directed to the victims and every ounce of fear felt alongside them. It can’t quite be classified as horror outright, but there are scenes that dance circles around the best in the genre, and are the most disturbing things to climb from the crevice of Fincher’s work. They’re nestled in a patient bog of studious detective work, blind speculation and frustrating herrings, which make them scarier than hell when they do show up out of nowhere. Adding to the already epic cast are Jimmi Simpson, Chloe Sevigny, Elias Koteas, John Carroll Lynch, Donal Logue, Pell James, Philip Baker Hall, John Terry, Zach Grenier and a brief cameo from Clea Duvall. I think the reason the film works so well and stands way above the grasp of so many other thrillers like it is because of its steadfast resolve to tell you exactly what happened, urge you to wonder what the missing pieces might reveal should they ever come to light, and deeply unsettle you with the fear of the undiscovered, something which never fails to ignite both curiosity and dread in us human beings.

Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy: A Review By Nate Hill

Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy is one of the most unsettling film experiences you will ever sit through, and the damn thing is only 90 minutes. It’s disconcerting, ambiguous and seems to exist simply to spin the viewer’s anxiety reflex into a storm and make our stomach turn loops. It’s a trim entry into the psychological upset sub genre, and puts a frazzled looking Jake Gyllenhaal through a wringer as he pursues a mysterious doppelgänger through the streets of Toronto, a bustling city that feels oddly desolate as glanced upon by Villeneuve’s camera, adding to the themes of paranoia and mental unrest. Gyllenhaal plays a twitchy college professor who is stuck in a closed loop routine: he gives lectures at the local university, drives home to his emotionally inaccessible girlfriend (Melanie Laurant), rinse and repeat. A chink appears in the chain when he becomes aware of another man in the city who appears to be his identical twin. The other man is a small time actor with a pregnant wife (Sarah Gadon) and a decidedly more nasty approach to the situation than the professor. The two of the, circle each other in a disturbing game of not so much cat and mouse, but Jake and Jake, both of them having not a clue as to what is going on, the edges of madness inching closer to both of their perception. Are they twins? Are there even two? Is it just one of them, losing their mind? There’s very freaky dream sequences with the constant imagery of spiders, both large and small, and what do they mean? Who’s to tell? Denis has stated in interviews that there is both rhyme and reason to his creation here, but whether he will ever divulge them remains to be seen. Perhaps it’s better left illusory, a formula for entrancing audiences that has already proved to work well for David Lynch. The moment that the man behind the curtain reveals the conscious meaning of his very subconscious efforts, the spell is no doubt broken. In any case, it’s a very hard film to process or focus on, our nerves jittering constantly and sabotaging any modicum of rational though that we might employ in deciphering the piece. This may be called style and atmosphere over substance by some, but even in not comprehending what’s going on, we feel deeply that there is some sort of cryptic cohesion if we are able to feel between the lines, maybe coming up empty handed ultimately, but knowing within us that we’ve attained wealth to our soul simply by bearing witness. I can’t say it’s a film that I love, or that I would watch again, but it’s certainly one that won’t leave my memories any time soon, and that is an achievement no matter how you look at it. It’s also got one of the scariest and most unexpected endings to any film I’ve ever seen, taking you so off guard that you feel like you’re going to have a coronary. It’s filmed in sickening piss yellow saturation which adds to the overall disconcerting nature, and quite the striking colour choice as well. I can see why this one was released with little fanfare or marketing, despite the presence of heavyweights Villeneuve and Gylenhaal. It’s difficult stuff, a movie that frustratingly soars above your head, onward towards its intensely personal and psychological destination. It’s up to us to jump, grasp and attempt to reach as high as the piece in order to get what we will out of it. Good luck.

DAN GILROY’S NIGHTCRAWLER — A REVIEW BY NICK CLEMENT

Unnerving. Unforeseeable. Unforgettable. Writer/director Dan Gilroy’s thrillingly caustic media satire Nightcrawler shows some seriously vicious teeth, taking you on a dark and twisted trip through nocturnal Los Angeles, all shot in 2.35:1 Mann/Refn-vision by the obscenely talented Robert Elswit, with James Newton Howard’s moody synth-dominated score pounding away in the background. Jake Gyllenhaal is utterly brilliant as Lou Bloom, a diseased creature of the night, appearing in virtually every scene, totally live-wire, spewing rapid fire dialogue with sociopathic glee. Shades of Travis Bickle abound in his portrayal of a freelance videographer hustling from crime scene to crime scene trying to sell his gruesome and exploitive footage to the highest buyer. This is the best performance of Gyllenhaal’s career so far, and over the past few years, he seems incapable of not being thoroughly excellent in whatever he appears in (Brothers, Source Code, End of Watch, Prisoners, Enemy, Everest; still need to see Southpaw). It’s great to see Renee Russo in a substantial role again, as she brings sass and class to her role as a beleaguered news producer. She gets to cut a nasty portrait of what it might be like to run a struggling local news station in the big-city that’s fighting for a piece of the ever-competitive ratings pie. Original movies from a single voice seem less and less common these days, and as Nightcrawler races through its propulsive and lurid narrative, you begin to realize that you’re watching something that’s playing by its own sick and cynical set of rules, unafraid to peek at the nastiness that’s running through our cities, news outlets, and members of society. This is an instant classic that defies expectations, and a film that’s gotten richer and richer on repeated viewings. Hopefully Gilroy has a new project on the horizon sooner than later…

DAVID FINCHER’S ZODIAC — A REVIEW BY NICK CLEMENT

David Fincher’s quest to become the new Alan Pakula hit new heights with his riveting serial killer/investigative journalism thriller Zodiac, which might possibly be his greatest accomplishment yet as a filmmaker. I’m never sure, to be honest, what Fincher’s “best” film is — you could make the case for nearly all of them in one way or another. But with Zodiac, he tapped into our worst fears (that of a killer on the loose) and mixed the expected genre elements with an amazing sense of time and place, vividly recreating San Francisco during the late 60’s and early 70’s, as well as demonstrating a perfectionist’s eye in terms of both small and large narrative and visual details. The trio of Jake Gyllenhaal, Mark Ruffalo, and Robert Downey Jr. all did sterling work in this film, each of them carving out a unique portrait of obsessive behavior that would consume their characters at all times. The dense, phenomenally well-researched screenplay by James Vanderbilt (writer/director of the upcoming Dan Rather drama Truth) requires more than one viewing to accurately parse out all of the pieces of information, while Fincher’s steady, engrossing directorial aesthetic grips the viewer with paranoia and subtle style.

The late, great cinematographer Harris Savides (Birth, The Game, Elephant) gave Zodiac an amazing visual texture, with the digital photography augmenting all of the nighttime sequences with a realistic sense of light quality, while capturing the grisly murders with stark and brutal effectiveness on 35 mm film. The supporting cast hammered home all of their work with rigorous perfection, with standout peformances on display by John Carroll Lynch, Anthony Edwards, Brian Cox, Philip Baker Hall, John Getz, Dermott Mulroney, John Terry, Donal Logue, Elias Koteas, Chloë Sevigny, and Adam Goldberg. David Shire’s creepy musical score smartly used period-authentic pop songs with an unnerving ambient soundtrack to maximum effect, while Angus Wall’s fleet, razor-sharp editing kept the two hour and 40 minute film feeling light on its feet; rarely do “long” movies feel this quick. Despite excellent critical support, the film didn’t catch on with the Academy (maybe it was the March release date or the middling box office returns), and while 2007 was a landmark year for cinema in general, Zodiac being left out of the big dance feels incredibly short-sighted. This is one of Fincher’s most absorbing films, filled with three dimensional and vulnerable characters that you root for, while showcasing a mystery that literally has no ending.

BALTASAR KORMAKUR’S EVEREST — A REVIEW BY NICK CLEMENT

Other than the various physical locations on display during Baltasar Kormákur’s matter-of-fact mountain climbing film Everest, the star of the show is ace cinematographer Salvatore Totino, who clearly went to huge lengths to accurately portray the harrowing conditions that the various individuals faced during that infamous summit of the world’s tallest mountain. Every single shot in this film feels authentic, if there was any CGI used its seamless, and there are some sequences that defy understanding, as it truly seemed that people’s lives were in jeopardy. You also get some vistas of overwhelming beauty, with Everest’s sense of scale never lost on the viewer; this film feels epic in scope yet intimate in the fine details. We’ve seen over the top action films set on a mountain (Vertical Limit) and there have been some great docudramas (K2 and Touching the Void come to mind), but in Everest, the verisimilitude becomes one of the key selling points, with the audience never taken out of the picture due to hokey staging or poorly constructed moments of adventure. Totino’s visceral camerawork covers the action with a great sense of danger and exhaustion, never betraying spatial geography in order to get “a money shot,” always allowing for the natural beauty of the images to take center stage over camera tricks or a generally over-stylized aesthetic. The helicopter rescue sequence towards the end is riveting, with more than one instance of “how is this being done” running through my head while watching, and the last shot of the film has a poetically haunting quality that feels very resonant in light of all that has come before it. Totino’s work is Oscar-caliber, and my hope is that his smart and incredibly composed work gets the attention it deserves.

It’s a miracle that anyone survived at all, and the film certainly reinforces the notion that the will to live is buried deep within all of us, and when put to the test, we’ll do just about as much as we can in order to keep breathing for another day. But hey, when you reach the roof of the earth, you’re bound to face some challenges, if not stare death itself directly in the face. The fact that many climbers lost their life during this particular ascent is no surprise; the details of this story were first outlined in Jon Krakauer’s bestselling novel Into Thin Air. Kormákur and his screenwriters, William Nicholson and Simon Beaufoy, effectively set the stage during the brisk first act in a very traditional fashion, as we get to know the various people who have decided to pay a small fortune to risk their lives. The cast is led by an excellent Jason Clarke, one of the various group leaders who made it their job to bring people all the way to the top of whatever mountain they were scaling, but who prided himself in always bringing people safely back down. Death hangs over this film, as it does in so many man vs. nature survival dramas, and its inescapability can sometimes feel suffocating and overly sentimental. Not here. Kormákur doesn’t over-play the sudden moments where people meet their fate; they’re simply here one minute and gone the next. Yes, you get scenes were loved ones make their final phone calls, but from what I’ve read, all of this occurred in real life, making these sequences all the more emotionally accessible and relatable. Keira Knightley destroys her one “big” scene, eliciting tears because of how honest the entire moment feels, and because you know that she’s trying her hardest to be strong in the face of all but certain tragedy. Jake Gyllenhaal, Josh Brolin, John Hawkes, Emily Watson, and Robin Wright are all terrific in their supporting roles, but it’s Sam Worthington who really surprises during the final act, becoming the film’s heart and soul, handling his scenes with a direct emotional intensity that keeps the film from ever becoming maudlin. Everest gets the job done with class and respect.