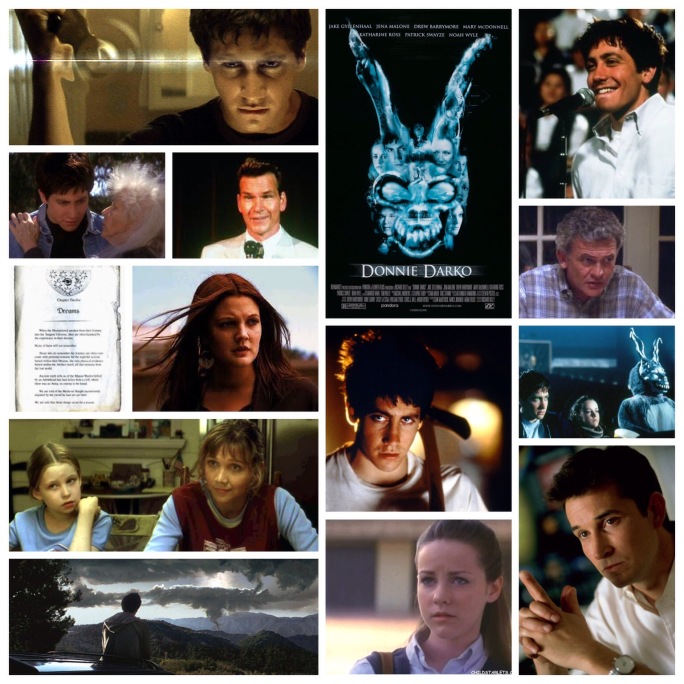

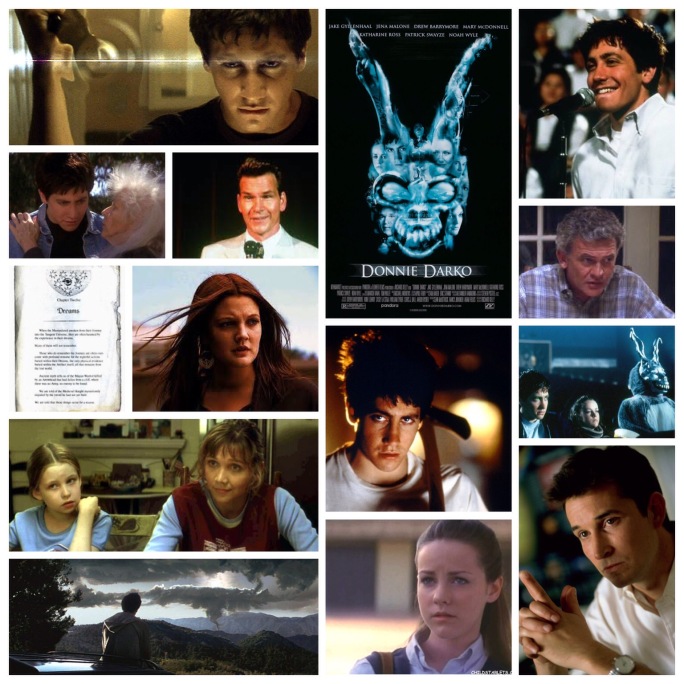

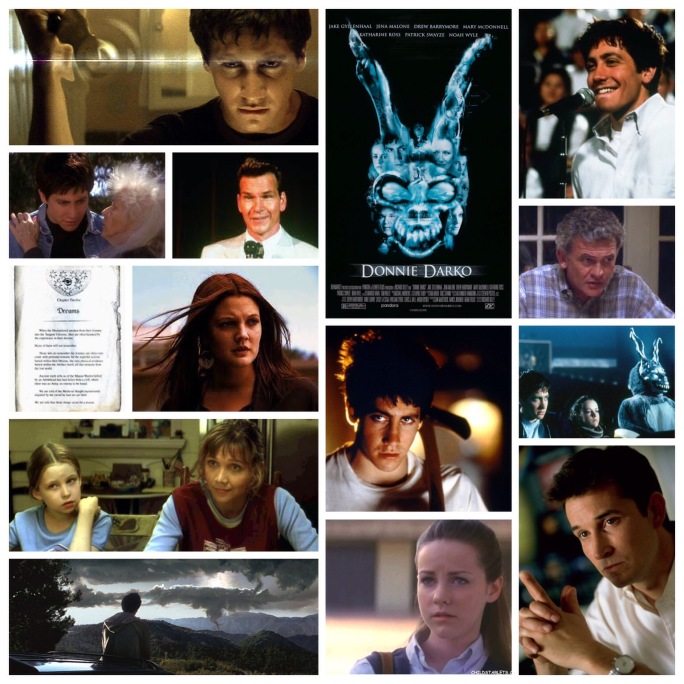

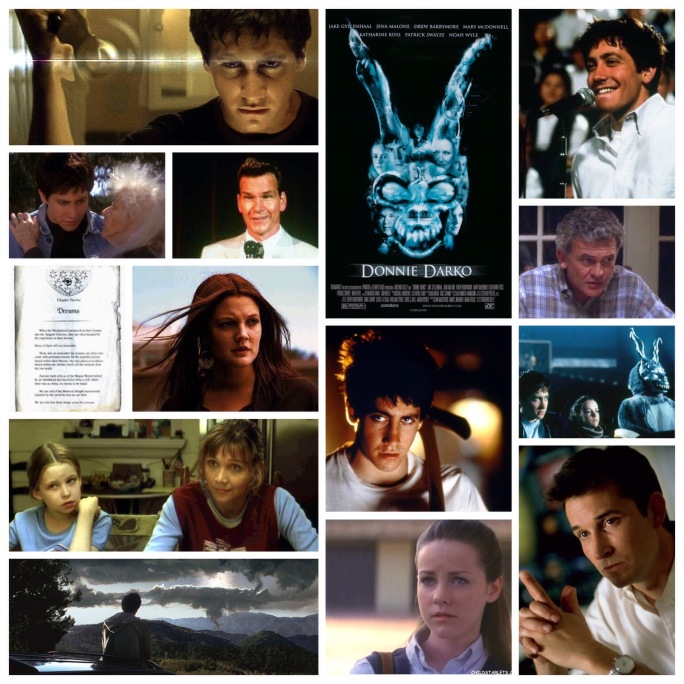

The director’s cut of Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had watching a film. It transports you to its many layered dimension with unforced ease and tells it’s story in chapters that feel both fluid and episodic in the same stroke. It has such unattainable truths to say with its story, events that feel simultaneously impossible to grasp yet seem to make sense intangibly, like the logic one finds within a dream. These qualities are probably what lead to such polarized, controversial reactions from the masses, and eventual yearning to dissect the hidden meaning which at the time of its release, didn’t yet have the blessing of the extended cut and it’s many changes. A whole lot of people hate this movie, and just as many are in love with it as I am. I think the hate is just frustration that has boiled over and caused those without the capacity for abstract thought to jump ship on the beautiful nightmare this one soaks you in. Movies that explore the mind, the unexplainable, and the unknowable are my bread and butter, with this one taking one of the premier spots in my heart. Kelly has spun dark magic here, which he has never been able to fully recreate elsewhere (The Box is haunting, if ultimately a dud, but his cacophonic mess Southland Tales really failed to resonate with me in the slightest). Jake Gyllenhaal shines in one of his earliest roles as Donnie, a severely disturbed young man suffering through adolescence in the 1980’s, which is bad enough on its own. He’s also got some dark metaphysical forces on his back. Or does he? Donnie has visions of an eerie humanoid rabbit named Frank (James Duval) who gives him self destructive commands and makes prophetic statements about the end of the world. His home life should be idyllic, if it weren’t for the black sheep he represents in their midst, displaying behaviour outside their comprehension. Holmes Osborne subtly walks away with every scene he’s in as his father, a blueprint of everyone’s dream dad right down to a sense of humour that shows he hasn’t himself lost his innocence. Mary McDonnell alternates between stern and sympathetic as his mother, and he has two sisters: smart ass Maggie Gyllenhaal (art imitating life!) and precocious young Daveigh Chase (also Lilo and Samara from The Ring, funnily enough). The film also shows us what a showstopper high school must have been in the 80’s, with a script so funny it stings, and attention paid to each character until we realize that none are under written, and each on feels like a fully rounded human being, despite showing signs of cliche. Drew Barrymore stirs things up as an unconventional English teacher, Beth Grant is the classic old school prude who is touting the teachings of a slick local motivational speaker (Patrick Swayze). The plot is a vague string of pearls held together by tone and atmosphere, as well as Donnie’s fractured psyche. Is he insane? Are there actually otherworldly forces at work? Probably both. It’s partly left up to the viewer to discern, but does have a concrete ending which suggests… well, a lot of things, most of which are too complex to go into here. Any understanding of the physics on display here starts with a willingness to surrender your emotions and subconscious to the auditory, visual blanket of disorientation that’s thrown over you. Just like for Donnie, sometimes our answers lies just outside what is taught and perceived, in a realm that has jumped the track and exists independently of reality and in a period of time wrapped in itself, like a snake eating it’s own tail. Sound like epic implications? They are, but for the fact that they’re rooted in several characters who live in a small and isolated community, contrasting macro with micro in ways that would give David Lynch goosebumps. None of this malarkey would feel complete without a little romanticism, especially when the protagonist is in high school. Jena Malone is his star crossed lover in an arc that finds them spending little time together, yet forming a bond that that feels transcendant. Soundtrack too must be noted, from an effective opener set to INXS’s Never Tear Us Apart to the single most affecting use of Gary Jules’s Mad World I’ve ever heard. It’s important that you see the director’s cut though, wherein you can find the most complete and well paced version of the story. There’s nothing quite like Donnie Darko, to the point where even I feel like my lengthy review is stuff and nonsense, and you just have to watch the thing and see to truly experience it.

Tag: Mary McDonnell

Donnie Darko: A Review by Nate Hill

The director’s cut of Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is one of the most profound experiences I’ve ever had watching a film. It transports you to its many layered dimension with unforced ease and tells it’s story in chapters that feel both fluid and episodic in the same stroke. It has such unattainable truths to say with its story, events that feel simultaneously impossible to grasp yet seem to make sense intangibly, like the logic one finds within a dream. These qualities are probably what lead to such polarized, controversial reactions from the masses, and eventual yearning to dissect the hidden meaning which at the time of its release, didn’t yet have the blessing of the extended cut and it’s many changes. A whole lot of people hate this movie, and just as many are in love with it as I am. I think the hate is just frustration that has boiled over and caused those without the capacity for abstract thought to jump ship on the beautiful nightmare this one soaks you in. Movies that explore the mind, the unexplainable, and the unknowable are my bread and butter, with this one taking one of the premier spots in my heart. Kelly has spun dark magic here, which he has never been able to fully recreate elsewhere (The Box is haunting, if ultimately a dud, but his cacophonic mess Southland Tales really failed to resonate with me in the slightest). Jake Gyllenhaal shines in one of his earliest roles as Donnie, a severely disturbed young man suffering through adolescence in the 1980’s, which is bad enough on its own. He’s also got some dark metaphysical forces on his back. Or does he? Donnie has visions of an eerie humanoid rabbit named Frank (James Duval) who gives him self destructive commands and makes prophetic statements about the end of the world. His home life should be idyllic, if it weren’t for the black sheep he represents in their midst, displaying behaviour outside their comprehension. Holmes Osborne subtly walks away with every scene he’s in as his father, a blueprint of everyone’s dream dad right down to a sense of humour that shows he hasn’t himself lost his innocence. Mary McDonnell alternates between stern and sympathetic as his mother, and he has two sisters: smart ass Maggie Gyllenhaal (art imitating life!) and precocious young Daveigh Chase (also Lilo and Samara from The Ring, funnily enough). The film also shows us what a showstopper high school must have been in the 80’s, with a script so funny it stings, and attention paid to each character until we realize that none are under written, and each on feels like a fully rounded human being, despite showing signs of cliche. Drew Barrymore stirs things up as an unconventional English teacher, Beth Grant is the classic old school prude who is touting the teachings of a slick local motivational speaker (Patrick Swayze). The plot is a vague string of pearls held together by tone and atmosphere, as well as Donnie’s fractured psyche. Is he insane? Are there actually otherworldly forces at work? Probably both. It’s partly left up to the viewer to discern, but does have a concrete ending which suggests… well, a lot of things, most of which are too complex to go into here. Any understanding of the physics on display here starts with a willingness to surrender your emotions and subconscious to the auditory, visual blanket of disorientation that’s thrown over you. Just like for Donnie, sometimes our answers lies just outside what is taught and perceived, in a realm that has jumped the track and exists independently of reality and in a period of time wrapped in itself, like a snake eating it’s own tail. Sound like epic implications? They are, but for the fact that they’re rooted in several characters who live in a small and isolated community, contrasting macro with micro in ways that would give David Lynch goosebumps. None of this malarkey would feel complete without a little romanticism, especially when the protagonist is in high school. Jena Malone is his star crossed lover in an arc that finds them spending little time together, yet forming a bond that that feels transcendant. Soundtrack too must be noted, from an effective opener set to INXS’s Never Tear Us Apart to the single most affecting use of Gary Jules’s Mad World I’ve ever heard. It’s important that you see the director’s cut though, wherein you can find the most complete and well paced version of the story. There’s nothing quite like Donnie Darko, to the point where even I feel like my lengthy review is stuff and nonsense, and you just have to watch the thing and see to truly experience it.

Margin Call: A Review by Nate Hill

J.C. Chandor’s Margin Call sustains a laser focused, wilfully meticulous look at the days leading up to the 2008 financial crash, showing us life within one wall street office building during a nervy period which now no doubt is remembered as the calm before the storm. Various characters in different positions of the hierarchy anxiously brace themselves as the jobs begin to get cut and the dread looms towards them like the inevitable rising sun at dawn. It’s set all in one afternoon and night, compacting a far reaching event which spanned years into the microcosm of a single 24 hour window, a tactic which sits through the larger world implications and brings it in for something a little more intimate. Zachary Quinto plays a young trader who discovers a rip in the lining of the economic infrastructure, a precursor to the eventual disaste. I’m not being purposefully vague and cryptic with that, I just don’t personally understand all the exact ins and outs of what went wrong back then, and having not the slightest knowledge of wall street jargon, that’s the best I can do. He brings this knowledge to his superiors who react in varying ways. Kevin Spacey is a disillusioned big shot who sees his life going off the rails alongside the country’s market, and mopes in his swanky office. Paul Bettany is a cocky young upstart who uses casual indifference to shade the bruises he’s got from knowing what will happen. Demi Moore is a company head who looks out for herself while others in the company. Jeremy Irons provides scant moments of humour as a bigwig fixer who arrives on a chopper to set things straight, or at least assess the damage. The best work of the film comes from Stanley Tucci (surprise, surprise) as a jilted employee who has been laid off in the confusion, and is seething about it. His melancholic monologue about what it takes to propel America’s industry and economy forward resonates with a humanity that cuts deep. The film ticks along with a pace that’s both measured and swift, with little time for introspect, yet showing it to us anyway amid the chaos. Watch for appearances from Penn Badgley, Al Sapienza, Simon Baker and Mary McDonnell as well. Chandor let’s the proceedings thrum with an inevitability that hangs in the air as the promise of the impending crisis, a feeling that serves to impart not why it happened, not how it happened, but the fact that it did happen, to each and every individual person who was affected, as opposed to the country as a whole.