Michael Cimino’s Year Of The Dragon is a visceral blast of pure Americana as only the man could bring us. It kills me that he suffered through that whole Heaven’s Gate fiasco (which is actually a really good movie, but that’s another story and argument entirely) because it extinguished any hopes of him making future films, and in doing so the studios effectively committed genocide against their own. Sure the guy was crazy as hell, but damn could he ever make a great film. This one is one of the most criminally overlooked cop flicks of all time, partly due to Cimino’s scorching direction and partly due to a a performance of monolithic grittiness from Mickey Rourke as Captain Stanley White, the cop who won’t stop. White is fresh out of Nam and mad as hell, launching a unilateral crusade of racist violence and self righteous fury against the Chinese crime syndicate in New York City, particularly a young upstart in their organization named Joey Thai (John Lone). Thai is as ruthless as White is determind, and the two clash in ugly spectacle, causing leagues of collateral damage on either side and inciting them both to roar towards an inevitable, bloody conclusion. Thai’s elderly superiors warn him of men like White, men who are fuelled purely by anger, bitterness and nothing else, smelling the fire and brimstone in the air and wisely stepping out of the way. Thai is of a younger, more petulant generation and foolishly decides to meet the beast head on by essentially kicking the hornet’s nest. White is warned by his caring wife (Caroline Kava) and fellow cop and friend Lou (Raymond J. Barry is excellent, firing Rourke up further with his work) not to mess with such a dangerous crowd. He has a volatile relationship with a beautiful Chinese American reporter (Arianne is the only weak link in the acting chain) who puts herself on the line for him by digging around in dangerous corners. The intensity level of this film is something straight from the adrenal gland; even in episodic scenes of introspect we feel the hum of the character’s emotions, and when the conflict starts again, which it does in fast and furious amounts, the actors are simply in overdrive. Rourke has never been better than he was in the 80’s, it was just his zenith of power. This isn’t a role that gets a lot of recognition, but along with Angel Heart, Rumble Fish and Pope Of Greenwich Village, I think it’s his best. He puts so much of himself into Stanley White that the edges which separate performer from performance begin to blur and waver, until we are locked into his work on a level that goes beyond passive consumption of art and elicits something reflective in us. Not to sound too hippie dippy about it, but the guy is just that fucking good. On the calmer side of the coin, John Lone brings both evil and elegance to Joey, a slick surface charm that’s constantly disturbed by Rourke’s hostility, leading to an eventual meltdown that’s very cool to see in Lone’s expert hands. This is one for the ages and should be in the same pantheon with all timers like Heat, Serpico, The French Connection and others. Rourke fires on all cylinders, as do his colleagues of the craft, and Cimino sits cackling at the switchboard with a mad calm, yanking all the right levers in a frenzy of unhinged genius. Not to be missed.

Tag: Mickey Rourke

SIN CITY: A DAME TO KILL FOR – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

In 2005, Robert Rodriguez adapted the comic book Sin City into a film with help from its creator Frank Miller who co-directed it. Convincing the veteran comic book writer/artist to come on board was a smart move on the filmmaker’s part as it assured that Miller’s luridly violent noir tales would be faithfully translated. This was achieved through a then-groundbreaking green screen environment that allowed Rodriguez to place his actors in Miller’s stylish world with a striking look comprised of black and white with strategic splashes of color. This innovative approach attracted a star-studded cast that included Bruce Willis, Mickey Rourke, Clive Owen and Benicio Del Toro among others. The final result dazzled audiences and was a commercial success.

A sequel seemed inevitable, but instead Rodriguez went on to team up with Quentin Tarantino on the box office misfire that was the Grindhouse double bill (2007) while Miller applied the Sin City aesthetic to a disastrous adaptation of Will Eisner’s comic book The Spirit (2008). Over the years, talk of a sequel surfaced occasionally with the likes of Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie being mentioned in potential leading roles. Nine long years later and the stars (and money) aligned for Rodriguez and Miller to reunite with Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014). The film promptly tanked at the box office and received mixed to negative reviews. What happened? Did Miller and Rodriguez wait too long? A green screen-heavy film is no longer a novelty. Two cast members with characters in the film had passed away and some roles have been recast. The general consensus seems to be that they waited too long to make a sequel and interest in the film had waned.

Some might complain that A Dame to Kill For is just more of the same. As a big fan of the first film this is not necessarily a bad thing. After seeing Sin City, I wanted to see more of Miller’s stories brought to life. In addition to adapting A Dame to Kill For and the short story “Just Another Saturday Night” from the Booze, Broads, & Bullets collection, Miller created two new stories specifically for the film – “The Long Bad Night” and “Nancy’s Last Dance.” By doing this, he has given the fans a real treat by offering two stories where the outcome is not known and introducing new characters into this universe.

In “Just Another Saturday Night,” Marv (Rourke) wakes up amidst a car accident unable to remember how he got there. He proceeds to recall what happened via flashback on a snowy Saturday night. This segment is a nice way to reacquaint us to the brutal yet darkly humorous world of Sin City. “The Long Bad Night” introduces us to Johnny (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), a confident gambler who decides to take on Senator Roark (Powers Boothe), the most powerful man in the city, in a high-stakes poker game and gets more than he bargained for. It’s a lot of fun to see Joseph Gordon-Levitt square off against Powers Boothe, the former playing a young upstart and the latter an evil, influential man.

The centerpiece of the film is “A Dame to Kill For,” which features Dwight McCarthy (Josh Brolin) as a private investigator taking photographs of a businessman (Ray Liotta) cheating on his wife with a hooker (Juno Temple). When the man tries to kill her, Dwight intervenes. He has a tortured past, which involves keeping his homicidal impulses in check. Afterwards, Dwight gets a call from an ex-lover by the name of Ava Lord (Eva Green), a beautiful woman married to a very rich man. She’s in some kind of trouble and he finds himself drawn into her tangled web yet again. He soon runs afoul of her imposing bodyguard Manute (Dennis Haysbert) who proceeds to work him over. Realizing that he’s out of his depth and bent on rescuing Ava, Dwight enlists Marv’s help, which only complicates things in typical noir fashion.

In “Nancy’s Last Dance,” Nancy Callahan (Jessica Alba) is an exotic dancer still haunted by the death of her lover John Hartigan (Bruce Willis) and is obsessed with avenging his death by killing Roark, the man responsible for it. Over time, she’s counseled/haunted by Hartigan’s ghost, which drives her increasingly crazy.

Actors Josh Brolin, Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Eva Green slip seamlessly into the Sin City world. It helps that they have that old school noir look, especially Brolin with his chiseled tough guy features and gravelly voice – perfect for his character’s voiceover narration. In no time, the actor makes you forget that he plays a character once portrayed by Clive Owen. Gordon-Levitt is excellent as the young newcomer with a secret and manages to elicit sympathy for his ultimately doomed character. Green plays Sin City’s reigning femme fatale. The stunning actress has an alluring, exotic look and can turn a vulnerability on and off at will all the while playing a cold-hearted manipulator of men. Green gives key line deliveries the right venomous spin that makes Ava Lord a fearsome figure in this world.

It’s great to see Mickey Rourke return to the role of Marv, a character he inhabits so well. He brings a world-weary charm and a much-needed dose of dark humor to the film. Powers Boothe, who only had a minor role in the first film, gets a much meatier part in A Dame to Kill For and it’s a lot of fun to see him sink his teeth into such a deliciously evil character. Unfortunately, Jessica Alba is once again miscast as Nancy, the stripper with a heart of gold. While she looks the part, the actress doesn’t have the chops to pull off the tricky evolution of character that goes from sweet girl traumatized by the death of loved one to a revenge-obsessed vigilante. Miller’s stylized dialogue needs to be delivered a certain way. Some actors can pull it off and others can’t. Alba falls into the latter category and it becomes painfully obvious in her segment. Even her dancing is unconvincing.

While it no longer has the technological novelty factor as an incentive (shooting it in 3D really didn’t help either), there is certainly no other film out there that looks like Sin City. There have been a few imitators since, most notably The Spirit and Max Payne (2008), but the look of the film is so specific to its universe that few have dared to emulate it. Rodriguez has said that with the first Sin City he held back somewhat stylistically for fear that it would be too much for audiences. Emboldened by its commercial success, he took the look further and made it even more faithful to Miller’s comic book. So, there are things like Ava being rendered in black and white accentuated with red lips and green eyes, and visual flourishes like Marv recounting past exploits while a tiny car chase revolves around him, or the moody storm clouds that hang heavy in the cemetery where Nancy visits Hartigan’s grave. And why not? It’s not like the characters or the world they inhabit are based on any kind of reality. They exist in a hyper-stylized neo-noir universe drenched in atmosphere.

The dialogue in A Dame to Kill For is riddled with clichés and the characters are drawn from archaic stereotypes, but that’s the point. Miller is paying homage to the Mickey Spillane crimes stories he clearly idolizes. The film immerses itself in noir clichés and wears them proudly like a badge of honor, refusing to make any excuses for trading in them. There’s really nothing more to it than that, which may make the film seem instantly forgettable, but Rodriguez’s film never aspires to be art as it is unrepentedly sexual and violent with very few if any redeeming characters. The first Sin City film came out at the right time and tapped into popular culture zeitgeist. A Dame to Kill For is not so lucky, but you have to give Miller and Rodriguez credit for sticking to their guns and delivering another faithful adaptation of the comic book, which may only appeal to fans and probably won’t convert the uninitiated.

SIN CITY – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

Until recently, most adaptations of independent comic books were far more successful (and by successful I mean faithful to their source material) than long-running mainstream ones from the two largest comic book companies, Marvel and DC. One only has to look at examples, such as Ghost World (2001), American Splendor (2003) and Hellboy (2004) against the failures of Catwoman (2004), Elektra (2004) and Constantine (2005). So, why are the first three films more satisfying triumphs and the last three empty exercises in style? The answer is simple. In the case of the first three movies, the filmmakers wisely allowed the comic book creators direct involvement in the filmmaking process, whether it was working on the screenplay (as with Ghost World and Hellboy) or actually appearing in the movie (American Splendor).

In the past, the comic book creator was, at best, a peripheral presence in the filmmaking process, or not even included at all. With bigger, longer running series, like Spider-Man or Superman, it is much harder to include the creator because there is not just one but many who have worked on the comic book over the years. Where does the filmmaker even start in these cases? To be fair, with Iron Man (2008) began a great run of adaptations of Marvel Comics being successfully translated to the big screen but before it the examples were few and far between.

It only makes sense that if one is going to adapt a comic book into a film that it be faithful in look and tone to its source material. Otherwise, why adapt it in the first place? Of course, there is always the danger of being too faithful to the look of the comic and not being faithful to its content (characterization, story, dialogue, etc.) like Warren Beatty’s take on Dick Tracy (1990) — all style and no substance. It goes without saying that the next logical step would be to include its creator, if possible, in the process so as to achieve the authenticity and integrity of the source material. Filmmaker Robert Rodriguez took this notion to the next level with Sin City (2005) by having its creator Frank Miller co-direct the movie with him. In fact, Rodriguez is so respectful of Miller’s work that he not only has the artist’s name listed first in the directorial credit but also displays his name prominently above the film’s title.

Sin City began as a series of graphic novels created by Miller. They are loving homages to the gritty pulp novels Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane and classic film noirs from the 1940s and 1950s. Miller’s world — the dangerous, crime-infested Basin City — is populated by tough, down-on-their-luck losers who risk it all to save impossibly voluptuous women from corrupt cops and venal men in positions of power through extremely violently means in the hopes of ultimately redeeming themselves. The movie ambitiously consists of three Sin City stories: That Yellow Bastard, The Hard Goodbye, and The Big Fat Kill with the short story, “The Customer is Always Right” acting as a prologue.

In the first story, Hartigan (Bruce Willis), a burnt-out cop with a bum-ticker and on the eve of retirement, is betrayed by his partner (Michael Madsen) after maiming a vicious serial killer (Nick Stahl) of young girls who also happens to be the son of the very power Senator Roark (Powers Boothe). The next tale features a monstrous lug named Marv (Mickey Rourke) who wakes up in bed with a dead prostitute named Goldie (Jaime King) and decides to get revenge on those responsible for killing the only thing that mattered in his miserable life. The final segment focuses on Dwight’s (Clive Owen) attempt to keep the peace in Old City when the prostitutes who run the area unknowingly kill a high profile (and also a sleaze bag) cop named Jack Rafferty (Benicio del Toro) and in the process risk destroying the precarious truce between the cops and the hookers that currently exists.

The three main protagonists are all well cast. Bruce Willis is just the right age to play Hartigan. With the age lines and the graying stubble on his face, he looks the part of a grizzled, world-weary cop with nothing left to lose. Willis has played this role often but never to such an extreme as in this film. Quite simply, Mickey Rourke was born to play Marv. With his own now legendary real life troubles and self-destructive behavior well documented, the veteran actor slips effortlessly into his role as the not-too-bright but with a big heart hero. British thespian Clive Owen is a pleasant surprise as Dwight and is more than capable of convincingly delivering the comic’s tough guy dialogue. As he proved with the underrated I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (2003), Owen is able to project an intense, fearsome presence.

The larger-than-life villains are also perfectly cast. Nick Stahl exudes deranged sleaze as Roark, Jr. and cranks it up an even scarier notch or two once he undergoes his “transformation” as the Yellow Bastard of his story. Perhaps one of the biggest revelations is the casting of Elijah Wood as the mute cannibal Kevin. Nothing he has done previously will prepare you for the absolutely unsettling creepiness of his character. Finally, Benicio del Toro delivers just the right amount reptilian charm as Jackie-Boy. Not even death stops him from tormenting Dwight and it is obvious that Del Toro is having a blast with this grotesque character.

Miller’s pulp-noir dialogue may seem archaic and silly but it is actually simultaneously paying homage and poking fun at the terse, purple prose of classic noirs and crime novels of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Rourke, Willis and Owen fair the best with this stylized dialogue as they manage to sell it with absolute conviction. It helps that both Rourke and Willis have voices perfectly suited for this kind of material: weathered and worn like they have smoked millions of cigarettes and downed gallons of alcohol over the years.

Of the women in the cast, Jessica Alba is the only real miscast actress. Not only does she not look like her character, Nancy Callahan (who was much more curvy, full-bodied and naked most of the time in the comic) but she does not go all the way with the role and her line readings feel forced and unnatural. Fortunately, Rosario Dawson more than makes up for Alba as Gail, an S&M-clad, heavily-armed prostitute who helps Dwight dispose of Rafferty’s body. She looks the part and inhabits her role with the kind of conviction that Alba lacks.

Finally, somebody has realized that the panels of a comic book are perfect storyboards for a movie adaptation. With Miller’s guidance, Robert Rodriguez has uncannily recreated, in some cases, panel-for-panel, Sin City onto film. He has not only preserved the stylized black and white world with the occasional splash of color from Miller’s comic, but also the gritty, dime-novel love stories that beat at its heart. Fans of the comic will be happy to know that virtually all of the film’s dialogue (including the hard-boiled voiceovers) has been lifted verbatim from the stories and the sometimes gruesome ultraviolence has survived the MPAA intact.

If you think about it, Rodriguez’s career has led him up to this point. With the stylized, over-the-top action of Desperado (1995), the pulp-horror pastiche of From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) and the mock-epic Once Upon a Time in Mexico (2003), he has been making comic book-esque movies throughout his career. It was only a matter of time before he adapted an existing one. Cutting his teeth on these action movies has allowed him to perfectly capture the kinetic action of Miller’s comic. Seeing hapless thugs fly through the air at the hands of El Mariachi’s deadly weapons in Desperado foreshadows the cops being propelled through the air when Marv makes his escape in Sin City.

What Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) did for the pulp serials of the 1930s and ‘40s, Sin City does for film noir. There is no question that Sin City resides at the opposite end of the spectrum from Sky Captain. While both feature retro-obsessed CGI-generated worlds, the former looks grungy and lived-in and the latter is pristine and perfect-looking. Sin City is absolutely drenched in the genre’s iconography: hired killers, femme fatales that populate dirty, dangerous city streets on rainy nights. It is the pulp-noir offspring of James Ellroy and Sam Fuller with a splash EC Comics gore. Ultimately, Sin City is a silly and cool ride and one has to admire a studio for having the balls to release a major motion picture done predominantly in black and white with the kind of eccentric characters, crazed violence and specifically-stylized world that screams instant-cult film.

B Movie Glory with Nate: The Courier

The Courier is a strange little flick that dabbles in the kind of pulpy narrative which the 80’s were famous for. One lone antihero sets out to deliver a package of enigmatic value to a recipient that is always one step ahead of him, proving to be quite elusive. Bad guys and gals hinder him at every turn and violence ensues, leading up to an inevitable confrontation and in this case a neat little twist that admittedly defies any sort of reason, yet is fun for the actors to play out and provides sensationalism, a trait that’s commonplace in such films. Jeffrey Dean Morgan is a haggard presence in any role, a guy you immediately feel rooted to in a scene. He gets the lead role here, playing an underground criminal courier, passing along dangerous goods from one cloak and dagger person to another. His latest task comes from his handler (Mark Margolis): Deliver an odd case to a reclusive criminal mastermind known only as Evil Sivle. Little information is given beyond that, but it soon becomes apparant that his mission is a cursed one, as he finds himself a hot target for all kinds of weirdos. German live wire Til Schweiger plays a dirty federal agent who hassles him with that campy charisma and narrow eyed theatricality that only he can bring to the table. Miguel Ferrer and Lilli Taylor are priceless as Mr. & Mrs. Capo, a pair of married contract killers who discuss their dinner plans whilst hunting their quarry, and have devised some truly vile torture methods involving culinary instruments. Yeah, it’s that kind of movie, where B movie mavericks are let off the chain and allowed to throw zany stuff into their otherwise pedestrian material that often borders on experimental. Morgan is assisted by a young chick (Josie Ho) who saves his ass more than a couple of times. Mickey Rourke shows up late in the game as Maxwell, a mysterious Elvis impersonator and Vegas gangster who plays a crucial role in Courier’s quest. Trust Rourke to take a derivitive, underwritten supporting character and turn the few minutes of screen time he has into utter gold that elevates his scene onto a plane which the film as a whole is sheepishly undeserved of. Morgan is better than the flick too, but he’s great in anything. He ducks the heroic panache of the action protagonist and dives into growling melancholy, his grizzly bear voice and imposing frame put to excellent use. This one got critically shredded upon release. Yeah it ain’t great, but it sure as hell ain’t terrible. Worth it for a cast that makes it work, and for that classic genre feel that can’t be beat.

RUMBLE FISH – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

History remembers Francis Ford Coppola’s, Rumble Fish (1983) as a film that was booed by its audience when it debuted at the New York Film Festival and in turn was viciously crucified by North American critics upon general release. It’s too bad because it is such a dreamy, atmospheric film that works on so many levels. It is also Coppola’s most personal and experimental project — on par with the likes of Apocalypse Now (1979). From the epic grandeur of The Godfather films to the excessive Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Coppola has pushed the boundaries, both on-screen and off. He has almost gone insane, contemplated suicide, and faced bankruptcy on numerous occasions, but he always bounces back with another intriguing feature that is visually stunning to watch. And yet, Rumble Fish curiously remains one of Coppola’s often overlooked films. This may be due to the fact that it refuses to conform to mainstream tastes and stubbornly challenges the Hollywood system with its moody black and white cinematography and non-narrative approach.

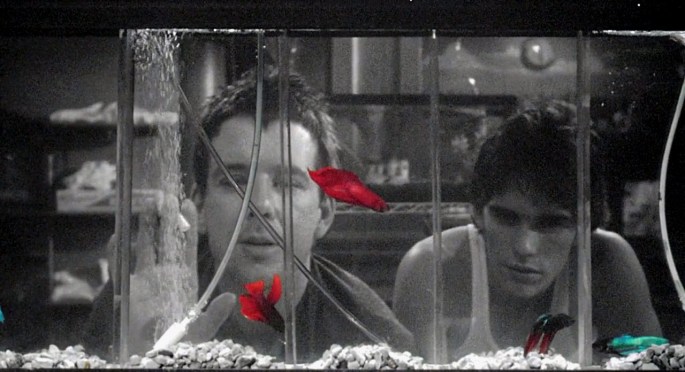

Right from the first image Rumble Fish is a film that exudes style and ambiance. It opens on a beautiful shot of wispy clouds rushing overhead, captured via time lapse photography to the experimental, percussive soundtrack that envelopes the whole film. This creates the feeling of not only time running out, but also a sense of timelessness. Adapted from an S.E. Hinton novel of the same name, Rumble Fish explores the disintegrating relationship between two brothers, Rusty James (Matt Dillon) and the Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke). The older brother derives his name from his passion: stealing motorcycles for joyrides. The film begins with the Motorcycle Boy absent, perhaps gone for good, while Rusty James tries to live up to his brother’s reputation: to act like him, to look like him, and, ultimately, to be him. Rusty James’ brother is viewed as a legend in the town as he was the first leader of a gang and also responsible for their demise.

Much like Harry Lime in The Third Man (1949), the Motorcycle Boy is initially physically absent, but his presence is felt everywhere — from the shots of graffiti on walls and signs that read, “The Motorcycle Boy Reigns,” to the numerous times he is referred to by characters. This quickly establishes him as a figure of mythic proportions. When the Motorcycle Boy finally does appear — during a fight between Rusty James and local tough, Biff Wilcox (Glenn Withrow) — it is a dramatic entrance on a motorcycle like Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953). This appearance marks a significant change in the film. We begin to see the world through the eyes of the Motorcycle Boy, almost as if the whole film is taking place in his head.

Consequently, Rumble Fish is shot entirely in black and white to simulate his color blindness. We even begin to hear the world like he does: voices sound echoey, disembodied, with his own heartbeat threatening to drown everything else out. It is this existential worldview that makes the Motorcycle Boy a tragic character. The rest of the film explores his attempts to come to grips with this outlook and his relationship with Rusty James, who views him as a hero — a label that the older sibling has never been able to accept.

Coppola wrote the screenplay for Rumble Fish with Hinton on his days off from shooting The Outsiders (1982). As the filmmaker said in an interview, “the idea was [that] The Outsiders would be made very much in the style of that book, which was written by a 16-year old girl, and would be lyrical and poetical, very simple, sort of classic. The other one, however, Rumble Fish, which she wrote years later, was more adult, kind of Camus for teenagers, this existential story.” Coppola even went so far as to make the films back-to-back, retaining much of the same cast and crew. Warner Brothers was not happy with an early cut of The Outsiders and chose not to distribute Rumble Fish. Despite a lack of financing, Coppola completely recorded the film on video during two weeks of rehearsals in a former school gymnasium, encouraging his young cast to improvise.

Actual filming began on July 12, 1982 on many of the same Tulsa, Oklahoma sets used in The Outsiders. The attraction to Rumble Fish, for Coppola, was the “strong personal identification” he had with the subject matter: a young brother hero-worships his older, intellectually superior sibling. Coppola realized that the relationship between Rusty James and the Motorcycle Boy mirrored his own connection to his brother, August. It was an older, more experienced August who introduced Francis to film and literature. Coppola always felt like he was living in the shadow of his brother and saw the film as a “kind of exorcism, or purgation” of this relationship.

As always, Coppola assembled an impressive ensemble cast for his film. From The Outsiders, he kept Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Glenn Withrow, William Smith, and Tom Waits, while casting actors like Mickey Rourke and Vincent Spano who were overlooked for roles in the film for one reason or another. They fill out their roles admirably, but Mickey Rourke in particular, is mesmerizing as the Motorcycle Boy.

To get Rourke into the mindset of his character, Coppola gave him some books written by Albert Camus and a biography of Napoleon. “There’s a scene in there when I’m walking down the bridge with Matt; and I’d try and stylise my character as if he was Napoleon,” the actor remembers. The Motorcycle Boy’s look was patterned after Camus complete with trademark cigarette dangling out of the corner of his mouth — taken from a photograph of the author that Rourke used as a visual handle. He portrays the character as a calm, low key figure that seems to be constantly distracted as if he is in another world or reality. Rourke “Methodically” conceived the Motorcycle Boy as being “an actor who no longer finds his work interesting.” To this end, he uses subtle, little movements and often cryptic phrases that only he seems to understand.

This feeling is further enforced by the two brothers’ alcoholic father, played brilliantly by Dennis Hopper in a surprisingly low key performance. He describes the Motorcycle Boy perfectly when he says that “he is merely miscast in a play. He was born in the wrong era, on the wrong side of the river. With the ability to be able to do anything that he wants to do and finding nothing that he wants to do.” Rourke’s Motorcycle Boy is almost embarrassed by the myth that surrounds him, that threatens to drown him. He openly rejects it when he says, “I’m tired of all that Robin Hood, Pied Piper bullshit. You know, I’d just as sooner stay a neighborhood novelty if it’s all the same to you… If you’re gonna lead people, you have to have somewhere to go.” It is this reluctance to embrace his legendary reputation that gives the Motorcycle Boy an element of humanity that was not in the novel.

Not only did Coppola assemble a talented cast of actors, but he also gathered an impressive crew to create the images and the proper mood to compliment them. The striking black and white photography of the film’s cinematographer, Stephen Burum, lies in two main sources: the films of Orson Welles and German cinema of the 1920s. Welles’ influence is particularly apparent in one scene where the Motorcycle Boy and Steve bring a wounded Rusty James home. While Steve and Rusty James talk in the background, the Motorcycle Boy looms into a close-up, as if the lens were a mirror in which he was admiring himself. He is clearly a character who suffers from what one critic called, “fatal narcissism,” a trait common in many of Welles’ films. This deep focus shot (a favorite of Welles) shows how far removed the Motorcycle Boy is from his brother and from everyone. He is like a mirror, impenetrable and impossible to read as Steve observes, “I never know what he’s thinking.” This scene harkens back to Welles’ masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941), which used the deep focus technique to give characters that look of “fatal narcissism,” to live a doomed existence.

Before filming started, Coppola ran regular screenings of old films during the evenings to familiarize the cast and in particular, the crew with his visual concept for Rumble Fish. Most notably, Coppola showed Anatole Litvak’s Decision Before Dawn (1951), the inspiration for the film’s smoky look, and Robert Wiene’s Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) which became Rumble Fish‘s stylistic prototype. Coppola’s extensive use of shadows (some were painted on alley walls for proper effect), oblique angles, exaggerated compositions, and an abundance of smoke and fog are all hallmarks of these German Expressionist films. Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1983), shot mainly in time-lapse photography, motivated Coppola to use this technique to animate the sky in his own film. The result is an often surreal world where time seems to follow its own rules.

Coppola envisioned a largely experimental score to compliment his images. He began to devise a mainly percussive soundtrack to symbolize the idea of time running out. As Coppola worked on it, he realized that he needed help from a professional musician. And so he asked Stewart Copeland, drummer of the musical group The Police, to improvise a rhythm track. Coppola soon realized that Copeland was a far superior composer and let him take over. The musician proceeded to record street sounds of Tulsa and mixed them into the soundtrack with the use of a Musync, a new device at the time, that recorded film, frame by frame on videotape with the image on top, the dialogue in the middle, and the musical staves on the bottom so that it matched the images perfectly. One only has to see Copeland’s evocative score matched with the film’s exquisite imagery to realize how well the musician understood Coppola’s intentions.

Rumble Fish is a rare example of a gathering of several talented artists whose collaboration under the guiding vision of a filmmaker results in a unique work of art. Why then, did the film receive such scathing reviews when it was released? The film alienated former head of production for Paramount, Robert Evans, who “remembers being shaken by how far Coppola had strayed from Hollywood. Evans says, ‘I was scared. I couldn’t understand any of it.'” Rumble Fish’s failure may have been due to the climate of American cinema at the time. The film was released in the early 1980s when art films and independent cinema were not as widely celebrated as they are now. Nobody was ready for a stylish black and white film with few big name stars and little sign of mainstream appeal. American critics and studio executives, on the whole, just did not “get it.”

It is a marvel that Rumble Fish was even made at all. Only Francis Ford Coppola’s unwavering determination and his loyal cast and crew could have made such a project possible. He had the clout and the resources to assemble such a collection of talented people to create a challenging film that acts as the cinematic equivalent of the novel by capturing its mood and tone perfectly. Every scene is filled with dreamy imagery that never gets too abstract but, instead, draws the viewer into this strange world. Coppola uses color to emphasize certain images, like the Siamese fighting fish in the pet store — some of the only color in the film — to create additional layers in this complex, detailed world.

With a few odd exceptions, Coppola has been content to merely rest on his laurels and reputation and crank out safe, formulaic films that lack any real substance or passion. Perhaps Coppola is tired from the numerous battles he has had with Hollywood studios over the years and simply does not have the energy to make the daringly ambitious films that he made during the ’70s and early ’80s. It is too bad, because Rumble Fish shows so much promise and creativity. Tossed off as a self-conscious art film, now that some time has passed, I see it as a movie clearly ahead of its time: a stylish masterpiece that is obsessed with the notion of time, loyalty, and family. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Coppola’s film is that it presents a world that refers to the past, present, and future while remaining timeless in nature.

Episode 18: TONY SCOTT’S DOMINO and Top Five Tony Scott and Mickey Rourke

We’re back with a regular episode! It’s been too long, so we’re here to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Tony Scott’s seminal film, DOMINO. Along with our thoughts on DOMINO, we also discuss our top five Tony Scott films and top five Mickey Rourke performances.

10TH ANNIVERSAY REVIEW OF TONY SCOTT’S MASTERPIECE DOMINO — BY NICK CLEMENT

Without question or hesitation, I can firmly state that Domino is my absolute favorite Tony Scott film, the one I keep coming back to the most, and at 10 years old, I feel it’s time that this insanely undervalued pièce de résistance from one of our ultimate modern auteurs got the critical attention and audience credit that it truly deserved. Ahead of its time yet also fabulously au courant when the film was unleashed upon cinemas in 2005, Domino is a smashing entertainment, the perfect synthesis of Scott’s gritty yet slick, highly aggressive style that he developed in the 80’s and 90’s with The Hunger, Top Gun, Days of Thunder, Beverly Hills Cop 2, Revenge, The Last Boy Scout, True Romance, Crimson Tide, and The Fan, which then led to a decidedly expressionistic (and at times impressionistic) aesthetic in the mid to late 2000’s, with such works as Man on Fire, Beat the Devil, Agent Orange, Déjà Vu, The Taking of Pelham 123, and his final film, the hard-charging and incredibly entertaining Unstoppable, pushing his trademark visual flourishes to the absolute extreme. Sandwiched in between were his two “silver-blue sheen” political thrillers Enemy of the State and Spy Game, with the former sort of predicting our post 9/11 world climate, and the latter commenting on it in real-time. But for me, Domino is the *Toniest* Tony Scott film that the iconic filmmaker ever crafted.

Easily one of the most misunderstood, sadly maligned films of the last decade, Domino is due to gain a much-deserved cult following. It bombed at the box office, and with the exception of a few sharp critics (Ebert, Dargis, Strauss), people really attacked Scott over this distinctly personal and hyperactive piece of purposefully heightened cinema. And make no mistake, like an effort by Picasso, Domino is a work of collage-inspired art, maybe the first piece of true cubist-cinema ever crafted, leading a super-charged group with the likes of Running Scared by Wayne Kramer, Joe Carnahan’s Smokin’ Aces and Stretch, Michael Davis’ Shoot ‘em Up, and Edgar Wright’s Scott Pilgrim vs.The World, all of which feel spiritually and stylistically connected to Scott’s over the top yet highly artistic sensibilities. Simply put, Domino is one of the most visually elaborate and sophisticated movies ever created, and all of these efforts feel birthed from the seismic contribution that Oliver Stone’s breakneck masterwork Natural Born Killers brought to the forefront in 1994, with its unrelenting sense of visual dynamism, outlandish humor, graphic violence, experimental tone and structure, and an emphasis on constant forward momentum. It’s also more important to note that Scott went on record as saying that Domino was his most favorite film that he ever directed; at the end of the day, he got the movie made the way he wanted to make it, and that says a lot in our current bean-counting movie climate.

I know that this is Scott’s most divisive, most critically savaged film. Many people hate it. Some people, like me, consider it to be the apex of Scott’s razzle-dazzle career as a storyteller and stylist, with a wild cast of characters (Keira Knightley, Mickey Rourke, Edgar Ramirez, Mo’Nique, Christopher Walken, Dabney Coleman, Delroy Lindo and many others) who all throw themselves into the filmmaking process with gusto and unending enthusiasm for the lurid material. The film is a slightly insane, pseudo-biopic of infamous bounty hunter Domino Harvey (the fantastic Knightley) that exists primarily as a showcase for Scott’s obsession with style and form and, as per usual, a heartfelt narrative. What makes Domino work as a whole is that the story is as unhinged as the style, always complimenting each other, always doing this crazy cinematic dance. Also, many people forget that much of the film takes place through a cloud of mescaline, and most of the third act incorporates a hallucinogenic-trip aspect to the proceedings. And then there’s Domino herself – a wild, rebellious British model turned bounty hunter who wanted only to march to the beat of her own drum. The real Domino Harvey did in fact lead a crazy life, but it probably wasn’t as over the top as Richard Kelly’s crisscrossing and zigzagging script, which was based on a story co-created by The Last Seduction scribe Steve Barancik. The filmmakers make it clear upfront that they’ve taken liberties with the facts – there’s even a graphic that reads: “Based on a true story…sort of.” What I love most about Domino is how frenetic and in your face the filmmaking is, and how incredibly intricate the plotting becomes by the finale. Scott’s hyperventilating and exhilarating style would mean diddly-squat if it wasn’t in service to an exciting plot with characters you like and stakes that are high. Knightley shredded her good-girl image with her balls-out performance as the titular heroine; from the lap-dance scene to breaking Brian Austin Green’s nose to busting out the double machine guns during the finale, she grabbed the role and ran with it. Mickey Rourke’s recent career resurgence really began here, with a gruff and stern performance as Domino’s boss. And Edgar Ramirez, who would later blaze up the screen in the epic five hour terrorist biopic Carlos, busted out in a big way as Domino’s volatile partner, Choco, and the love story that develops between them is as soft and tender as the rest of the film is jagged and primal.

Many complained that Scott’s directorial tricks and kinetic editing patterns were a major problem in Domino. To those individuals I say: Go home and watch Driving Miss Daisy. First off, lest anyone forget, the film is framed through the P.O.V. of a main character who is tripping on mind-altering substances – that should be the first sign to the viewer that the film is going to be a bit off-kilter. Kelly’s labyrinthine yet still coherent screenplay is a marvel of ingenuity, character construction, and dense plotting with a couple of his customary satiric zingers thrown in for good measure. Daniel Mindel’s super-saturated, kaleidoscopic cinematography bleeds with intense color as the images jump off the screen, assaulting and overwhelming the viewer’s senses – it’s a hot-blooded cinegasm of technique, designed to get you off. Repeatedly. And when you take into consideration that Kelly’s off-the-wall but still rooted in reality screenplay frequently shoots off in various directions at any given point, always carrying the potential to spin wildly out of control, you have to applaud the zeal of all the people behind this crazy undertaking. Strip away all the pyrotechnics and the nonlinear structure and you’re left with a rather simple story of love, deceit, revenge, and emotional and physical catharsis. And let me tell you – if you don’t find it cinematically satisfying when Keira Knightley and Mickey Rourke and Edgar Ramirez are speeding down that elevator shaft in the Stratosphere hotel while the penthouse level is exploding from an I.E.D., well, I’m not sure what to tell you!

There are just so many glorious sights that this movie has to offer: The epic opening credit sequence which needs to be played at full volume blast, Christopher Walken stealing scenes as a lunatic reality TV producer with a serious “font issue,” Ian Ziering and Brian Austin Green destroying their 90210 celebrity personas in hilarious cameos, Tom Waits as a tripped-out roamer of the desert with some poetic and interesting notions regarding fate, Knightley giving a bra and panty lap dance to a gang member in order to get her crew out of trouble – this movie never stops chugging and churning, throwing stuff at the audience, egging them on for a visceral response. The Jerry Springer interlude with the unveiling of the “mixed-race flow chart” is still a pisser for the ages, and overall, the bizarre nature of the narrative can never really be pinned down, which is a huge part of the fun factor. This was Tony Scot unleashed, the moment where you felt Scott put ALL OF HIMSELF into making a movie. It’s that rare, expensive, personal project that only gets funded by private investors who then let the filmmaker do whatever it is that they want. Domino is Tony Scott’s undying love letter to cinema as a whole and stands as his immortal masterpiece. As Manohla Dargis of the New York Times said in her glowing review of the film: “It’s all the Tony Scott you could want in a Tony Scott movie.” Damn straight.

TONY SCOTT’S MAN ON FIRE — A REVIEW BY NICK CLEMENT

Tony Scott’s slick, gritty and highly influential revenge thriller Man on Fire is over 10 years old (which seems insane to think about!) and it holds even more fiery resonance today than when it did upon first release. Brian Helgeland’s hard-nosed, straight-ahead screenplay set a simple foundation for Scott to run amok with his distinct brand of directorial tricks. The film is a stylistic tour de force and serves as a bridge from the post-Bruckheimer era to the more experimental/artiste period for the filmmaker. Mixing staccato editing patterns with mixed film-stock cinematography by the brilliant cameraman Paul Cameron (Deja Vu, Collateral) that occasionally borders on the avant-garde (Scott would push his maximalist style to the breaking point in his next film, the career-defining genre-bender Domino), Scott utilized wildly creative subtitles (notice the fonts and screen placement) and a hyper-layered soundtrack of both scored and sourced music and threatening ambient sounds, thus achieving a fractured-nightmare quality that sneaks up and envelopes the viewer, as it does lead character Creasey, played with stoic resilience by Denzel Washington. Bloody and violent but never unnecessarily so, the film has a mean-streak a mile wide, but also contains, like so many other Scott films, a seriously warm heart. The restless, nervy filmmaking aesthetic intelligently meshed with the damaged psychological complexities of Washington’s character; it’s a slow burn performance and one of Denzel’s absolute best and most compelling. And every bit his equal was Fanning, whose enormously affecting performance as the girl-in-trouble makes the viewer care each and every step of the way, no matter how dark and nasty things get within the framework of the story. Creasey’s about to paint his masterpiece, and we’re invited to the wild show. Man on Fire is one of the best examples of its genre.