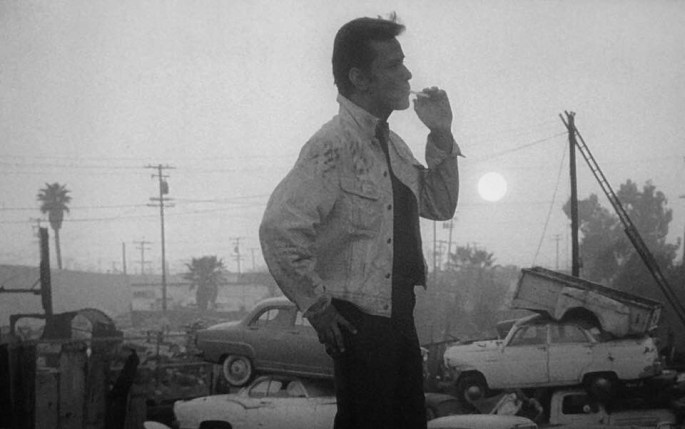

Where Russ Meyer’s previous features had generally begun with soft, laconic shots of nature that were coupled with a booming bowl full of earnest, corn-filled narration, Lorna’s mobile, ghost train opening shot promises to transport us to a place we’ve never been before. And, for sure, we eventually roll up to a man clad in black (credited as “The Man of God”) who stands in the middle of the road and immediately breaks the fourth wall, warning us of sin and judgement. The nudie cuties, it seems, were just the soft preliminaries. For when we’re eventually waved on by our ominous stranger and begin moving further down the road of iniquity, we’ve fully graduated into the real world of Russ Meyer. Welcome to Lorna, a film in which the titular character was promised as being “TOO MUCH FOR ONE MAN!” on its promotional one-sheet.

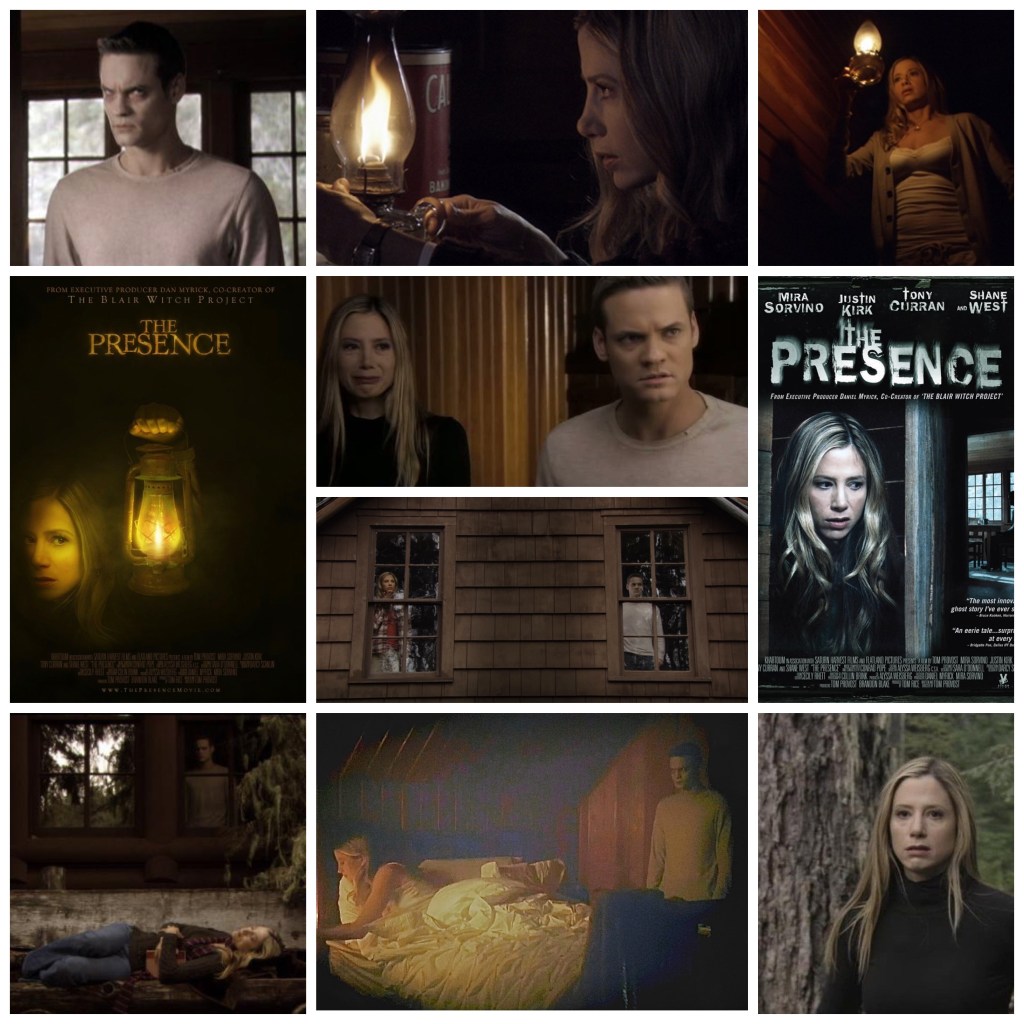

Envisioned and quickly written by Meyer and James Griffith (who also plays the ominous Man in Black), Lorna was Meyer’s first attempt at a true narrative where he would be calling all the shots. Fanny Hill, Meyer’s debut outside the confines of the nudie cutie, was such a miserable experience that he traded in that film’s costume-laden period decor for the starkness of Nowheresville, America. And where Fanny Hill had a mid-size cast that mostly had little to do, Meyer strips Lorna down to a world populated by ten people.

Lorna was the first in a long string of tongue-in-cheek morality plays constructed by Meyer in order so soft-peddle his cantilevered beauties. However, Lorna really plays it smart with those moral angles. The film begins as a standard roughie in the row houses of the backwater California town of Locke where Luther (Hal Hopper) and Jonah (Doc Scortt) stalk a drunken women named Ruthie (Althea Currier) to her house. There, their twisted sexuality is put on full display as Ruthie is beaten and raped by Luther while Jonah leers through a window. Down the river apiece, Lorna (Lorna Maitland) is a deadpan saint to her well-meaning but weak sauce husband, Jim (James Rucker) who is studying to becomes a CPA while working down at the salt mines with Luther and Jonah, the former forever chiding Jim about Lorna and her supposed infidelities which barely conceal his lustful coveting of her.

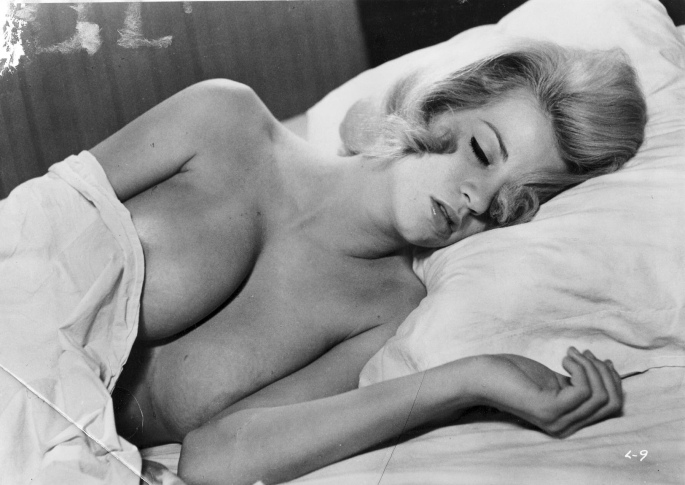

In truth, Lorna and Jim are fundamentally decent folks who, for no greater sin than being normal, flawed humans, get more misery heaped upon them than they probably deserve. Jim might be a wet mop whose cocksmanship isn’t anything to write home about, but he really isn’t a bad guy and he truly loves and cares for Lorna. And Lorna isn’t a bad woman, either. Treated like a thing on a pedestal, which she doesn’t necessarily object to, Lorna argues that perhaps this attitude can be taken a bit too far and that there is a decent-size chasm between being respected and being handled like a porcelain doll. And being stuck in a fishing shack with absolutely nothing to do all day and nobody around for miles, it’s not hard to fault Lorna when, after another disappointing night in bed with Jim, she goes out to onto the dock and more or less wishes upon a star to be whisked away toward a more exciting life, shown in a dazzling montage of neon burlesque over a much happier, undulating Lorna Maitland.

When an escaped convict stumbles his way through the marshes and eventually happens upon Lorna, he sexually assaults her which leads to a kind of physical deliverance for her. This is sort of a narrative blunder where the arcane convention of the “struggling woman who gives in to the passion” is taken to the outer limits of taste and decorum. While a certain contingency of more seasoned generations recognizes this kind of coded filmic language when they see it and mostly give it a pass, it’s hard to fault the reactions to those for whom the origins of this convention have been buried under layers and layers of film history, especially to those who aren’t familiar with the context of the roughie. But in Lorna, however ill-advised it seems in retrospect, I’m not totally convinced that this device isn’t executed for the benefit of Lorna’s character as she both takes control over the situation (thereby drawing a contrast to the earlier character of Ruthie), and achieves a long-needed sense of sexual release with the convict.

Whatever complications are apparent in the tact of sexualizing rape, Lorna mostly gets away with it due to the uncommon skill of Meyer as a filmmaker and his knack for throwing his characters into a blender and upending any preconceived notions about them. For like in a very sly play, everything in Lorna gets turned upside down in its second half, proving the liquidity inherent in quick-shifting morality. While it’s loaded to make it look like the ones who are punished are the ones who upend their marriage vows, Lorna actually dies for everyone’s sins. Would her relationship with the convict been different if Jim would have shown her the kind of care for her and their one year anniversary as he should have? And what does one make of Luther’s tearful breakdown at the end of the film as he finds some sort of redemption (if not complete absolution) when, not 70 minutes earlier, we watched him beat a woman senseless? As articulated in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, “It’s a strange world.”

But above all, Lorna was a way for Meyer to strut his stuff as director, producer, co-writer, editor, and photographer. Forever innovative, Meyer finds a clever way to reduce the strip teases of Europe in the Raw down to the restless Lorna, hot and bothered while her husband toils away at his studies in the another room, writhing around in their bed while bathed by chiaroscuro lighting. And Lorna, if nothing else, is economical. Lorna’s flashbacks are presented by heat waves over static shots of a running brook and Dutch angles of the church in which they’re married. Meyer also gets a lot of story by employing nothing more than a POV camera as a prison break is pulled off on a Saturday afternoon by grabbing a few pickup shots here and there and throwing an alarm sound effect over them. And if this were mere sexploitation, the beauty in the carefully designed and thought-out match cuts wouldn’t roll over the audience like a pleasant breeze. Nor would the hotted up climax, replete with axes and hooks, work like absolute gangbusters if not for Meyer’s skill as an editor.

In terms of casting, Lorna Maitland creates quite the mold as the first of Meyer’s superstars, defining the Meyer female outside of the nudie cuties as strong, highly libidinous, and yearning for her own identity. Special mention, too, should go to Hal Hopper who is just terrific as Luther and also co-wrote the film’s catchy theme song. If I were to find out that Hopper was a slobbering, high-wire nut job in real life (he wasn’t), I would not hesitate to believe it to be true as he literally embodies the kind of ghastly creep one spends most of their life avoiding.

Lorna was definitely a page-turner and game-changer for Meyer and laid a foundation upon which he could begin to build his very singular cinematic universe populated by decent people doing the best they can while toiling about in a judgmental, hostile, and unforgiving world littered with violence, betrayal, and poisoned passions. It also gave the world a heroine in whom a salacious promise of being too much for one man was entirely conditional on the broke-dick dude in question.

(C) Copyright 2021, Patrick Crain