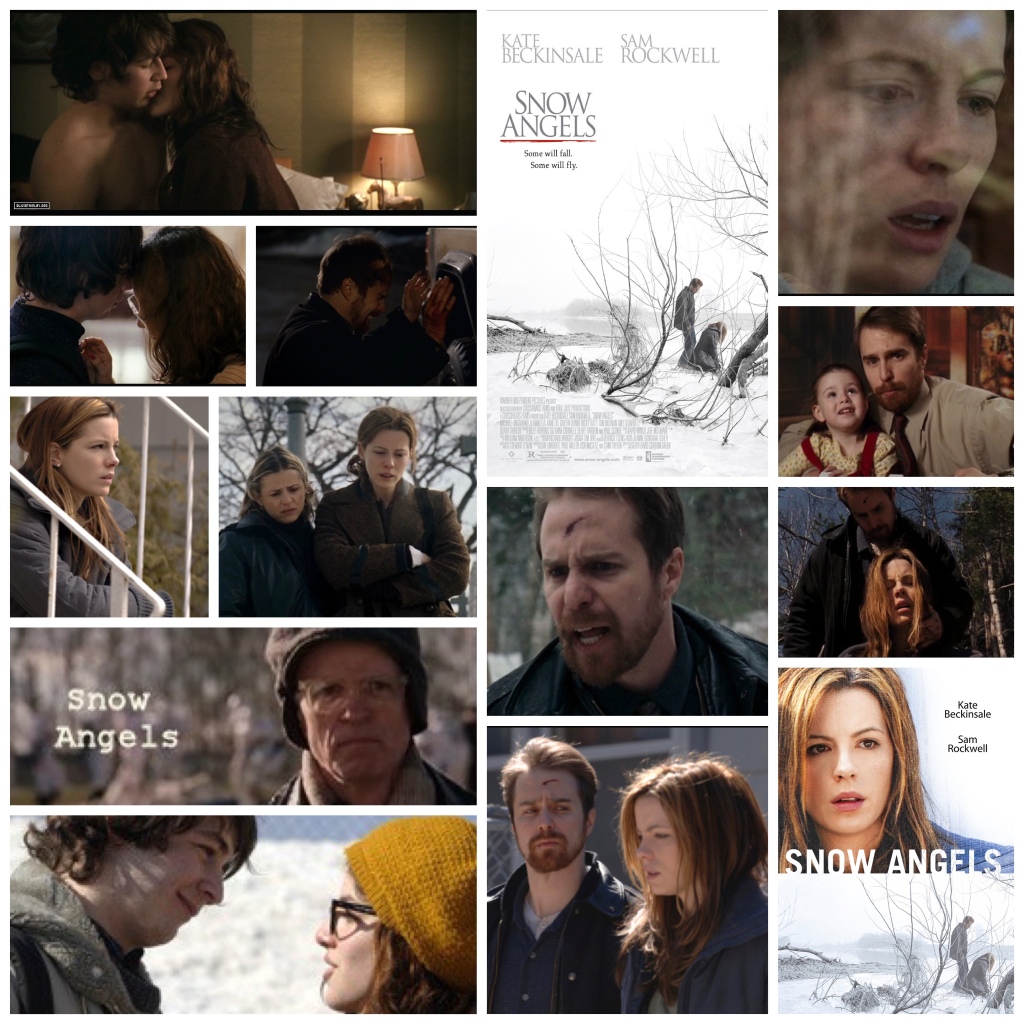

David Gordon Green’s Snow Angels is a film that asks the viewer to accept hard truths: that any given human being is capable of maliciousness, compassion, mistakes, volatility, naïveté and the desire to do better within the same lifetime. It presents to us an ensemble of small town characters at penultimate crossroads of their lives where decisions will be made that cannot be unmade, and may shape both their futures and our perceptions of character but we must remember… they’re only human. Resisting the urge to use any sort of filmmaking gimmickry, Green forges a blunt, unforgiving yet unusually honest portrait of these people: Sam Rockwell and Kate Beckinsale give heartbreaking, career best performances as hopelessly dysfunctional divorced parents who lose their way both as a unit and as individuals following the tragic death of their infant daughter. This event spirals out around them into the community as we see murder, adultery, budding teen romance and all manner of human interaction transpire. Rockwell is a careening time bomb of emotional immaturity, a man who loves his ex wife and loved his daughter dearly but cannot reconcile his own mental health issues and his performance implodes upon itself like a dying star in a work of art that has never seen this actor more vulnerable and raw. Beckinsale ditches her glossy, restrained pretty girl image for a character that it’s easy to dismiss as unlikeable and irresponsible until you see the depth and dimension she pours into the performance, and it’s not so easy to pass judgment or condemn. Others provide vivid impressions including Griffin Dunne, Amy Sedaris, Nicky Katt, Jeannetta Arnette and Tom Noonan who bookends the film in haunting profundity as a no nonsense high school band teacher who seems almost like a godlike force or deity watching over the souls of this small northwestern town. The single uplifting plot thread is a teen romance between Olivia Thirlby and Michael Angarano, who flirt adorably, fall for each other awkwardly and discover sex, conversation and each other’s company in a realistic, down to earth and warm-hearted way, it’s a cathartic oasis of love and light amidst the dark onslaught of this overall bleak snowstorm of a narrative. What makes all of this tragedy, pain and sorrow so palatable then, you may ask? Green is a terrifically intuitive director who gets genuinely believable performances from his actors, full of naturalistic dialogue, believable idiosyncrasies and a sense that nobody in this story is simply good, simply bad or there to serve one archetype, they are all flawed human beings capable of the deepest acts of love, caring and compassion or the most callous, nightmarish violence, neglect and abuse. There’s a scene where a mother comforts her teen son who has made a traumatizing discovery and she tells him how important it is not to keep that pain bottled up, but to feel through it and it’s one of many strikingly intimate, uncommonly intelligent scenes in a film that is a meticulously edited and shot carousel of human experience. The tag line read: “Some will fly, some will fall,” and it’s applicable to our our experience as human beings overall: life is not easy for everyone, mistakes are made, love is found and lost and the cycle continues. A lot can be learned, felt, internalized and reflected upon after watching this miracle of a film.

-Nate Hill