When you begin to consider the high-level talent that went into the formula that produced Robert Altman’s HealtH, it’s difficult to recall another movie in film history that was, and continues to be, treated as poorly. Coming directly after Altman’s twin failures of 1979, Quintet and a Perfect Couple, its production was relatively quick and on-the-fly; an attempt to get one in the can while things at 20th Century Fox were still being run by Alan Ladd, Jr., a staunch Altman proponent who once gave the maverick filmmaker a million and a half dollars to make 3 Women, a movie that came to Altman in a dream and had no real cohesive story.

When you begin to consider the high-level talent that went into the formula that produced Robert Altman’s HealtH, it’s difficult to recall another movie in film history that was, and continues to be, treated as poorly. Coming directly after Altman’s twin failures of 1979, Quintet and a Perfect Couple, its production was relatively quick and on-the-fly; an attempt to get one in the can while things at 20th Century Fox were still being run by Alan Ladd, Jr., a staunch Altman proponent who once gave the maverick filmmaker a million and a half dollars to make 3 Women, a movie that came to Altman in a dream and had no real cohesive story.

Sure enough, things did change and Ladd was ousted. HealtH, which had an initial scheduled release date in late 1979, began to get slowly pushed back on the schedule. Early 1980 came and went and a series of test runs arranged by the new management proved to be less than promising. The master plan of having it released before the 1980 presidential election never materialized. It’s safe to assume that when Altman began shooting the lavishly budgeted, dual-studio event picture Popeye in 1980, he couldn’t dream that he would get it shot, edited, and in theaters before HealtH.

But Popeye was released in time for Christmas in 1980 and HealtH was eventually pushed off of the Fox release schedule entirely. It did manage to play a limited engagement at Film Forum in 1982 but, aside from its occasional, stealthy appearance on various television movie channels, HealtH has never seen a release on home video. It’s a depressing world in which we live that Robert Downey Sr.’s similarly-imprisoned the Gong Show Movie finally gets a Blu ray release and HealtH can’t even be bought on the sad, used VHS market. Every once in a while, a widescreen rip from one of those movie channel broadcasts makes its way onto YouTube, but its difficult to know if it’s been edited for time or whether the somewhat squeezed visual presentation is a representation of the film’s true aspect ratio.

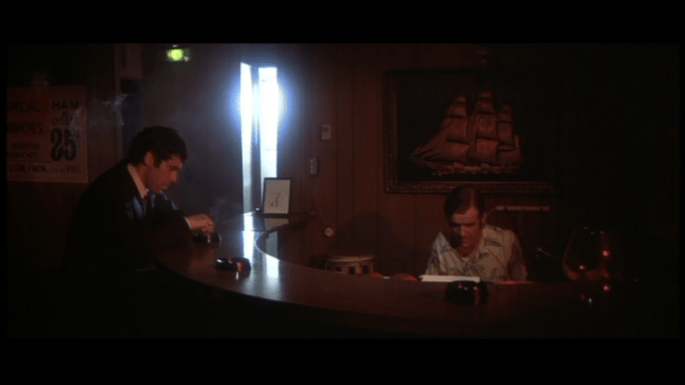

Given its obscurity, the perceived notion is that HealtH must be some kind of otherworldly dog of a film; a real hubristic bonanza crafted amidst a barrage of likeminded projects by Altman. But the truth of the matter is that HealtH is a surprisingly strong look at the ridiculousness of the American political system as filtered through the world of the then-bourgeoning consumer health industry. A fine addition to the busier, wide-canvas ensemble pieces Altman could engineer with remarkable skill and dexterity, HealtH performs double duty as a sly comedy and a prescient warning of the toxic injection of empty personality and media-driven messaging into our electoral process.

In a way, the overtly political overtones of HealtH would go on to serve Altman well when it came time for him to produce his masterpiece of the 80’s, Tanner ’88; one specific element, the jaunty campaign theme “Exercise Your Right to Vote,” is heard in both films. In its earlier incarnation, it’s delivered by The Steinettes, an a capella outfit who acts as a ridiculous but appropriate greek chorus to HealtH’s very odd portrait of 1979 America.

HealtH is, on the surface, about two days at a health convention in which two candidates are running for the title of “President of HealtH.” Present at this convention are product pitchmen, authors, political functionaries & fixers, glad-handing bureaucrats, dirty tricksters, aides, liaisons, and PR staff all centering around the two presidential hopefuls.

In one corner, Esther Brill (Lauren Bacall), 83 year-old virgin whose ubiquitous campaign slogan “Feel Yourself,” is delivered with an astounding cluelessness as Brill believes that each orgasm shaves 28 days off of your life. Her staff is made up of PR guru Harry Wolff (James Garner), oversexed campaign manager, Dr. Ruth Ann Jackie (Ann Ryerson) Brill’s undersexed personal physician who secretly lusts after Wolff, and a gaggle of nurses who are constantly drinking behind Brill’s back.

In the other corner is Isabella Garnell (Glenda Jackson) a pragmatic-yet-cold idealist whose speeches all seem swiped from Adlai Stevenson. Her entourage consists solely of Willow Wertz (Diane Stilwell), a sweet-natured aide whose ongoing sexual frustration is rooted in her inability to feel anything sexual for anything whatsoever.

Between the two candidates is Gloria Burbank (Carol Burnett), a representative from the White House and Wolff’s ex-wife; Dr. Gil Gainey (Paul Dooley), an independent candidate for president and shill for something called “Vita-Sea;” Colonel Cody (Donald Moffat), a bellowing political string-puller; Bobby Hammer (Henry Gibson), a slimy political operative sent to disrupt the Garnell campaign; Sally Benbow (Alfre Woodard), the convention hotel’s PR director; and, finally, Dick Cavett, as himself, who is there to cover the event for his talk show. Oh, yeah, and the Steinettes.

In the film, we’re told that HealtH (which stands for “Happiness, Energy and Longevity through Health”) is an organization more than three times the size of the NRA and whose members can be similarly motivated to vote one way or the other. So the film certainly exists in an America that could also produce the cockeyed presidential campaign of Nashville’s Hal Phillip Walker. But Walker didn’t much have a real-life counterpart in 1975. The populist politics of Nashville reflected a hopelessness that washed through the post-Watergate, pre-Carter country like a rotten fever. The politics of HealtH were much more immediate. While sending up the then-current political climate, the film seems to anticipate the cultural shift that occurred in the presidential election in 1980. Even if the other candidates in the film could be composites of many other political figures, Esther Brill is a certain representation of the perceived image of Ronald Reagan, a man who counted on a network of advisors and aides to keep him informed and aware and who was about to enter the presidential race with a boatload of sunny optimism and slogans aplenty.

While HealtH is far from perfect due to its unfocused and rushed production and its occasional tendency to get lost in the weeds of its own mix of satire and reality (you never really feel like you should be investing in it as you really should), there is a great deal to admire. The script, by Altman regular Frank Barhydt, actor Dooley, and Altman does an admirable job keeping the film equally steeped in reality (through the characters of Woodard and Garner), television (Cavett and, eventually, Dinah Shore), and fantasy (basically everything else). The performances, too, are all top-notch. Burnett, Bacall, and Jackson are all terrific but the film is absolutely stolen at every turn by Woodard whose polite facade hilariously begins to give way to disdain as the convention rolls along. Among the men, Garner turns in a reliably easy-going performance, Paul Dooley is as energetic as I’ve ever seen him, and Dick Cavett, remarkably comfortable in a sizable role, has a great deal of fun.

As history marches on, HealtH’s chances of being anything other than a completely forgotten and mostly unseen film become slimmer and slimmer. Altman passed away ten years ago so it’s unlikely that any other event could be the catalyst for its release. Sometimes chuckling and sometimes wincing while watching it in the midst of our own current presidential election that certainly seems like it could play out in an Altman film, it’s a cinch that HealtH could still find an audience today.

When you begin to consider the high-level talent that went into the formula that produced Robert Altman’s HealtH, it’s difficult to recall another movie in film history that was, and continues to be, treated as poorly. Coming directly after Altman’s twin failures of 1979, Quintet and a Perfect Couple, its production was relatively quick and on-the-fly; an attempt to get one in the can while things at 20th Century Fox were still being run by Alan Ladd, Jr., a staunch Altman proponent who once gave the maverick filmmaker a million and a half dollars to make 3 Women, a movie that came to Altman in a dream and had no real cohesive story.

When you begin to consider the high-level talent that went into the formula that produced Robert Altman’s HealtH, it’s difficult to recall another movie in film history that was, and continues to be, treated as poorly. Coming directly after Altman’s twin failures of 1979, Quintet and a Perfect Couple, its production was relatively quick and on-the-fly; an attempt to get one in the can while things at 20th Century Fox were still being run by Alan Ladd, Jr., a staunch Altman proponent who once gave the maverick filmmaker a million and a half dollars to make 3 Women, a movie that came to Altman in a dream and had no real cohesive story.

California Split is not afraid to show the ugly side of gambling. Bill sells his car and his possessions for a big poker game in Reno. Charlie exacts a rough, bloody revenge on the guy who mugged him at the beginning of the film. These are not always likeable guys and to Altman’s credit he doesn’t try to romanticize or judge them, leaving that up to the audience. Altman wanted to convey the empty feeling that winning from gambling gives these guys as he told Film Heritage magazine, “The mistaken feeling that winning…you can’t spend that money; you don’t go out and pay the milk bill with it unless you’re about to go to jail. It just means that you can play that much longer…In other words, it’s passes. It’s more tickets to the amusement park – that’s all it is.” California Split is arguably Altman’s loosest film in terms of plot and one of the richest in terms of character and observing their behavior.

California Split is not afraid to show the ugly side of gambling. Bill sells his car and his possessions for a big poker game in Reno. Charlie exacts a rough, bloody revenge on the guy who mugged him at the beginning of the film. These are not always likeable guys and to Altman’s credit he doesn’t try to romanticize or judge them, leaving that up to the audience. Altman wanted to convey the empty feeling that winning from gambling gives these guys as he told Film Heritage magazine, “The mistaken feeling that winning…you can’t spend that money; you don’t go out and pay the milk bill with it unless you’re about to go to jail. It just means that you can play that much longer…In other words, it’s passes. It’s more tickets to the amusement park – that’s all it is.” California Split is arguably Altman’s loosest film in terms of plot and one of the richest in terms of character and observing their behavior.