There is something about turning 30 that makes one re-evaluate their life. It is that time when you are forced to grow up, find direction, settle down, and become an adult. Beautiful Girls (1996) concerns a group of men faced with this dilemma. They have been living in the past and recent events have forced them to confront it head on. This is also the late director, Ted Demme’s best film in an all-too brief career. As he said in an interview at the time of the film’s release, “I don’t think there are too many movies about turning 30, or just about to turn 30. Those issues are whether to get married or not, whether to have kids or not, am I happy in my job, do I need to find another job, am I unsettled with myself. You’re not a teen anymore, and you don’t want to admit you’re an adult either.”

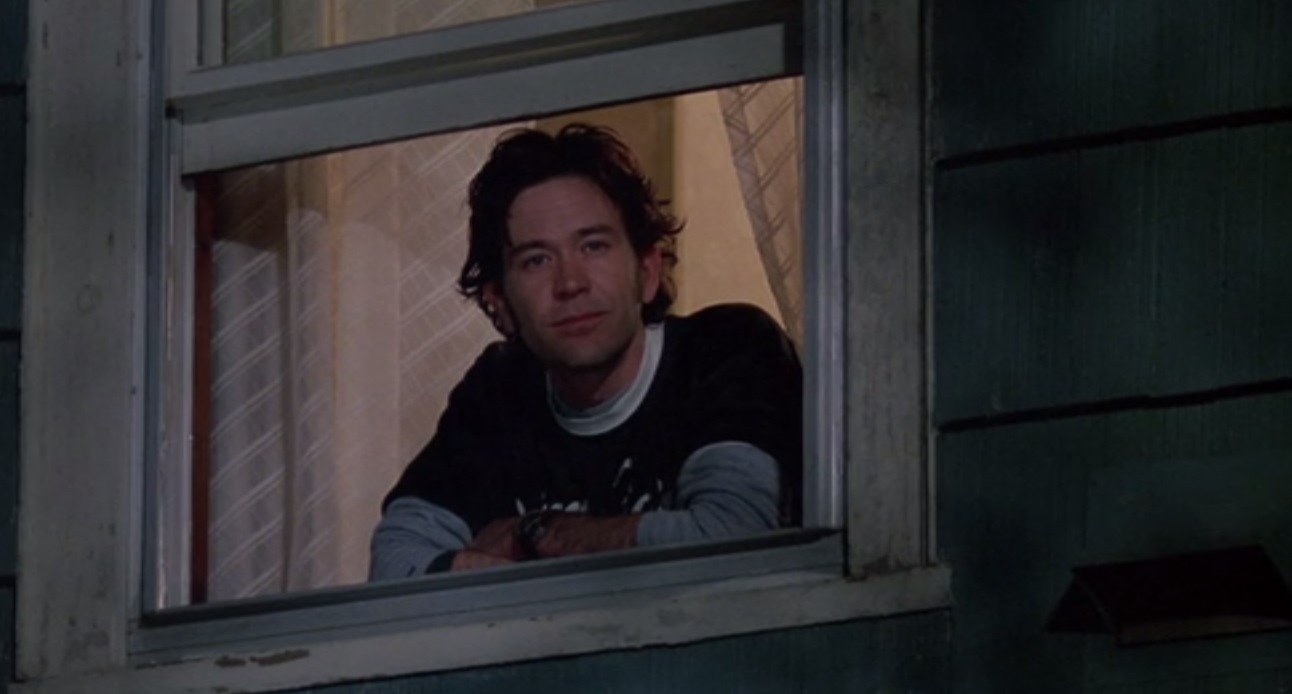

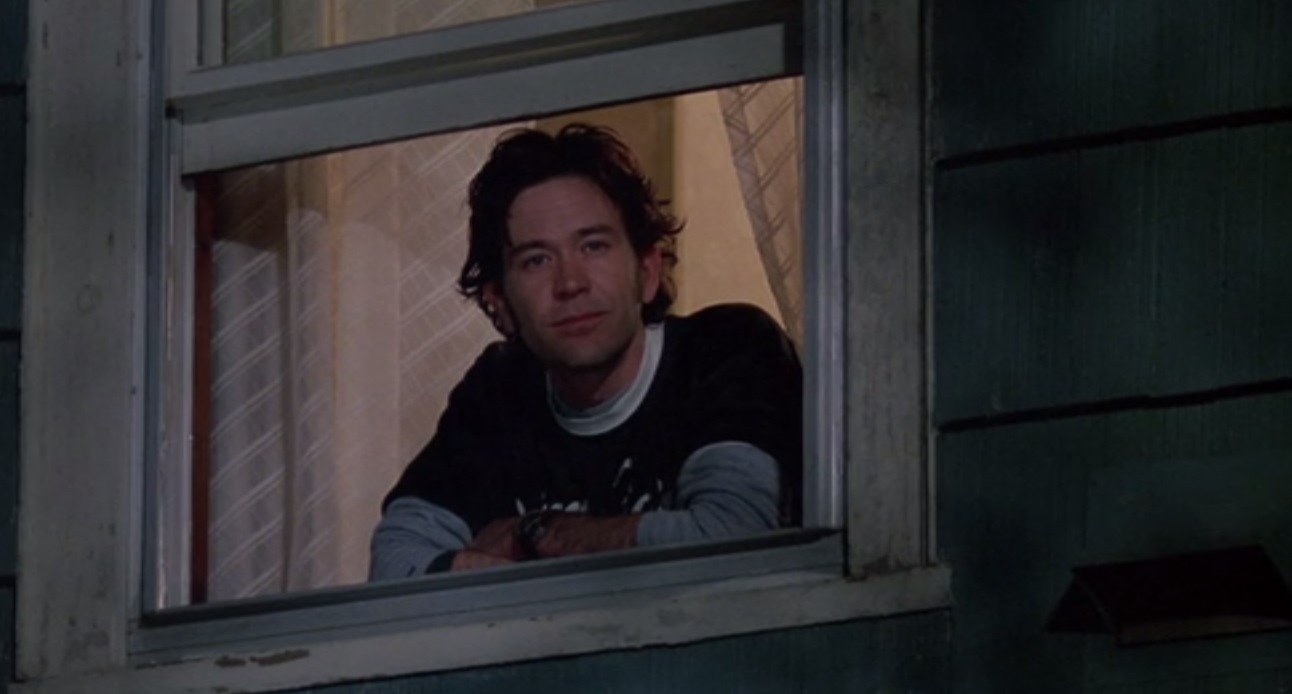

Willie (Timothy Hutton) returns to his small, Northeastern hometown for his ten-year high school reunion, hook up with buddies, and get his life in order. His mom has recently died (leaving his younger brother and father in a deep funk) and all of his friends are having relationship problems. Willie strikes up a friendship with a young girl named Marty (Natalie Portman) who has moved in next door. She is a character out of J.D. Salinger short story – wise beyond her years. Marty sets the tone for the rest of the women in the story. They are all intelligent and end up suffering with men who don’t appreciate what they have right in front of them.

Screenwriter Scott Rosenberg was living in Boston, waiting to see if Disney would use his script for Con Air (1997). “It was the worst winter ever in this small hometown. Snow plows were coming by, and I was just tired of writing these movies with people getting shot and killed. So I said, ‘There is more action going on in my hometown with my friends dealing with the fact that they can’t deal with turning 30 or with commitment’ – all that became Beautiful Girls.” The resulting screenplay turned out to be quite autobiographical, with Willie being Rosenberg’s surrogate.

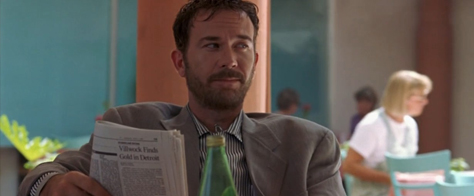

The friendship between Willie and Marty pushes the boundaries of what is comfortable in a comfort movie but it never goes beyond it. Rosenberg’s screenplay is smart enough to be self-aware of this and even addresses it in a scene between Willie and his friend Mo (Noah Emmerich). Fortunately, the film narrowly avoids letting things get too uncomfortable and therefore taking us out of the captivating spell established by the movie. It also avoids clichés like the beautiful Andrea (Uma Thurman) having sex with one of the guys. Instead, she rebuffs them all because she is loyal to her boyfriend who, makes her martinis listens to Van Morrison and reads the newspaper with her on Sunday mornings – simple pleasures. She is not a perfect ideal, just on another level than these guys.

Rosenberg’s script is also able to juggle the various subplots without resorting to cliché resolutions. Tommy (Matt Dillon) is cheating on his girlfriend Sharon (Mira Sorvino) with his high school sweetheart (Lauren Holly). When he gets beat up by her husband (Sam Robards) and his buddies you anticipate Willie, Paul (Michael Rapaport) and Mo to mobilize and kick some ass but at the last second they stop because the man’s child will see her father get beaten up. This stops Mo who also has kids.

In addition to the clever plotting, Rosenberg’s script also features a lot of funny, memorable dialogue. Tommy chastises Paul for getting his on again-off again girlfriend, Jan (Martha Plimpton) a brown-colored diamond when he tells him, “Buddy, you been eating retard sandwiches.” There is also great throwaway dialogue like Stinky (Pruitt Taylor Vince) with his proprietor lingo, “We got apps!” or the often-used word “crease” to convey frustration at something, like when Tommy asks, “What’s got him creased?”

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo.

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo.

The women in the film are smarter than the guys and make them (and us) feel like they are lucky that their behavior is even tolerated much less loved despite all of their failings. This is epitomized in Gina (Rosie O’Donnell)’s famous monologue where she chastises Tommy and Willie for obsessing over the women in Penthouse magazine. She tells them, “If you had an ounce of self-esteem, of self-worth, of self-confidence, you would realize that as trite as it may sound, beauty is truly skin-deep.” Gina speaks for the women in the film when she reminds the men to forget the airbrushed ideal of women that we see in magazines and movies. They do not exist or are unattainable to any normal guy.

To counter her argument, later on in the movie, Paul delivers a monologue defending men’s idealization for the impossibly perfect image of women. “She can make you feel high full of the single greatest commodity known to man – promise. Promise of a better day. Promise of a greater hope. Promise of a new tomorrow.” It is a rare, articulate moment for Paul, suggesting that he may be more than some lunkhead who drives a snowplow. He may actually be a romantic. It is nice to see a film that is obviously told from a man’s point of view trying to show both sides of the argument.

The women in the film are not treated like excess baggage. They all have a soul and a brain which is rare for a film written and directed by men. There is a tendency to make them perfect or marginalized with their problems defining them. This is not the case with Beautiful Girls. This is reversed and it is the problems that define the men.

Ted Demme assembled a fantastic cast of independent character actors for his movie: Michael Rapaport, Max Perlich, Pruitt Taylor Vince and Mira Sorvino to name only a few. They all work so well together and their friendships are believable because of the preparation the director made them do. He had the entire cast come to Minneapolis and live together for two to three weeks so that they could bond. One only has to watch a scene like Andrea’s first appearance in Stinky’s bar as Willie and his friends try desperately to impress her that the two week bonding session paid off. There is an ease and casual nature between everyone that is authentic.

The setting is a character unto itself. Demme has set his film in a charming east coast hamlet that is filled with little diners and bars that look so inviting that you want to go there, you want to be there. It all looks so comforting, so inviting and this is so hard to achieve properly in any film. He commented in an interview that he “wanted to make it look like it’s Anytown USA, primarily East Coast. And I also wanted it to feel like a real working class town.” To this end, Demme drew inspiration from Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978). “The first third of the film is really an amazing buddy movie with those five actors. You could tell they were best friends, but they all had stuff amongst them that was personal to each one of them.” Demme wanted to make Beautiful Girls more than just a buddy movie. When he read Rosenberg’s screenplay he told him, “‘You know, we really need to take this to another level.’ If I was ever going to make a buddy movie, which I never thought I would, I wanted to make sure it had some real depth to it.”

The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.

The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo.

All of the guys in Beautiful Girls are essentially the same person. Willie is just finding his luck, Paul just lost his luck as the film begins, Tommy loses it over the course of the movie, and Mo has already found and achieved it with his family. Demme does not waste an opportunity to subtly illustrate his point. In one scene, he frames all three guys together: Paul (lost luck) is driving with Willie (finding luck) and Mo (achieved luck) along for the ride. The women counterpoint their men in this cycle: Tracy (Annabeth Gish) for Willie, Jan for Paul, Sharon for Tommy, and Sarah (Anne Bobby) for Mo. The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.

The film does not wrap everything up nice and neatly. Paul and Jan’s subplot is not resolved in the sense that we don’t know if they settle their differences and get back together. Tommy and Sharon will probably get back together but it is not spelled out. Instead, as the closing credits appear we are left to imagine what happens to the characters. It is Paul’s parting comments to Willie as he is about to go back to New York City, “Come and see us any time, Will. We’ll be right here where you left us. Nothing changes in the Ridge but the seasons.” This is also a message to the viewer as well. Come back and see Beautiful Girls again. The film’s world and its characters are comforting and making you want to revisit them again and again.