Walter Hill’s Streets Of Fire is just too good to be true, and yet it exists. It’s like the type of dream concept for a movie that you and your coolest friend think up after a bunch of beers and wish you had the time, money and resources to make yourself. It’s just cool right down to the bone, a beautiful little opus of 1950’s style gang trouble set to a so-good-it-hurts rock n’ roll soundtrack devised by the legendary Ry Cooper, Hill’s go to music maestro. It’s so 80’s it’s bursting at the seams with the stylistic notes of that decade, and both Hill and the actors stitch up those seams with all the soda jerk, greaser yowls and musical mania of the 50’s. Anyone reading up to this point who isn’t salivating right now and logging onto amazon to order a copy, well there’s just no hope for you. I only say that because for sooommeee reason upon release this one was a financial and critical dud, floundering at the box office and erasing any hope for the sequels which Hill had planned to do. I guess some people just aren’t cool enough to get it (can you tell I’m bitter? Lol). Anywho, there’s nothing quite like it and it deserves a dig up, Blu Ray transfer and many a revisit. In a nocturnal, neon flared part of a nameless town that looks a little like New York, the streets are humming with excitement as everyone prepares for the nightly musical extravaganza. Darling songstress Ellen Aim (young Diane Lane♡♡) is about to belt out an epic rock ballad in a warehouse dance hall for droves of screaming fans. There’s one fan who has plans to do more than just watch, though. Evil biker gang leader Raven Shaddock (Willem Dafoe, looking like Satan crossed with Richard Ramirez) kidnaps her as the last notes of her song drift away, his gang terrorizes the streets and disappears off into the night with poor Ellen as their prisoner. The locals need a hero to go up against Raven and rescue Ellen, and so estranged badass Tom Cody (Michael Paré) is called back to town after leaving years before. He’s a strong and silent hotshot who takes no shit from no one, and is soon on the rampage to Raven’s part of town. He’s got two buddies as well: two fisted, beer guzzling brawler chick McCoy (Amy Madigan), and sniveling event planner Billy Fish (Rick Moranis). That’s as much plot as you get and it’s all you need, a delightful dime store yarn with shades of The Outsiders and a soundtrack that will have your jaw drop two floors down. The two songs which Ellen sings are heart thumping legends. ‘Nowhere Fast’ gives us a huge glam-rock welcome into the story, and ‘Tonight Is What It Means To Be Young’ ushers us out with a monumental bang before the credits roll, and damn if Hill doesn’t know how to stage the two songs with rousing and much welcomed auditory excess that’ll have you humming for days. Paré is great as the brooding hero, and you won’t find too many solid roles like this in his career. He’s a guy who somewhat strayed off the path into questionable waters (he’s in like every Uwe Boll movie) but he pops up now and again I’m some cool stuff, like his scene stealing cameo in The Lincoln Lawyer. Dafoe clocks in right on time for his shift at the creepshow factory, giving Raven a glowering, makeup frosted grimace that’s purely vampiric and altogether unnerving. Him and Paré are great in their street side sledgehammer smackdown in the last act. Bottom line, this is one for the books and it still saddens me how unfavorably it was received… like what were they thinking? A gem in Hill’s career, and a solid pulse punding rock opera fable. Oh, and watch for both an obnoxious turn from Bill Paxton and a bizarre cameo from a homeless looking Ed Begley Jr.

Tag: Diane Lane

Judge Dredd: A Review by Nate Hill

Ah yes, the 90’s version of Judge Dredd, featuring a hopped up Sylvester Stallone as the titular comic book lawman. There is so much hate floating around for this flick that I feel like radios have picked up some of it right out of the air. There used to be a lot more loathing, but then the 2013 version graced our presence, and it was so good, so true to the source material and such a kick ass flick that the collective bad taste left the fan’s mouths, leaving this version somewhat forgotten and to many people, for good reason. But.. but… bear with me for just a moment, readers, and I’ll tell you why it’s not as bad as it’s utterly poopy reputation. Yes it’s silly, overblown, altogether ridiculous and Stallone takes off his helmet to yell about the law a lot. Basically pretty far from the source material and weird enough to raise eyebrows in many others, and prompt the torch and pitchfork routine from fans of the comic series. But it’s also a huge absurdist sci fi spectacle that will blow up your screen with its massive cast, opulent and decadent special effects and thundering, often incomprehensible plot. It’s in most ways the exact opposite of the 2013 version, all the fat that was trimmed off of that sleek, streamlined vehicle is left to dangle here, resulting in a chaotic mess that looks like a highway pileup between Blade Runner, Aliens and some Roger Corman abomination. But.. is it terribly unwatchable? Not in the least, or at least not to me. Like the highway pileup, it’s so off the rails that we can’t help but gawk in awe, and if we’re not some comic book fan who is already spiritually offended to the core by it, even enjoy that madness and lack of any rhyme or reason in it. Stallone uses his bulk to inhabit the character, and infuses a level of stagnant processed cheese to his dialogue that would be distracting if it weren’t for the electric blue contact lenses he sports the whole time, which look like traffic lights designed by Aqua Man. He’s embroiled in one convoluted mess of a plotline involving a former sibling (a hammy Armand Assante with the same weird eyes). Joan Chen and Diane Lane fill out the chick department, the former being some kind of cohort to Assante, and the latter a fellow judge alongside Dredd. Dredd has two superiors, the noble and righteous “” (Max Von Sydow in the closest thing he’ll ever make to a B-movie), and the treacherous Griffin (a seething, unbridled Jurgen Prochnow). The cast is stacked from top to bottom, including a rowdy turn from James Remar who sets the tone early on as a rebellious warlord who is set straight by Dredd. Rob Schneider has an odd habit of following Stallone around in films where his presence is wholly not needed (see Demolition Man as well), playing a weaselly little criminal who pops up whenever we’re off marveling at some other silly character, plot turn or risible costume choice. Scott Wilson also has an unbilled bit as Pa Angel, a desert dwelling cannibal patriarch, and when one views his scenery chomping cameo, although no doubt awesome, it’s easy to see why he had his name removed from the credits. The whole thing is a delightful disaster that shouldn’t prompt reactions of hate, at least from the more rational minded crowd. Yeah its not the best, or even all that good, but it’s worth a look just for the sake of morbid curiosity, and to see an entire filmmaking, acting and special effects team strive way too hard and throw everything into the mix, forgetting that less is more as they pull the ripcord of excess. Sure I’m generous, but I’d rather be puzzled and amused rather than bitter and cynical when a lot of work still went into this and me as an average joe has no right to bring down artists when my greatest life accomplishments so far are riding a bike with no hands while I have a beer in one and check my phone in the other. Such silliness is what we find in this movie, and I gotta say I was tickled by it.

RUMBLE FISH – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

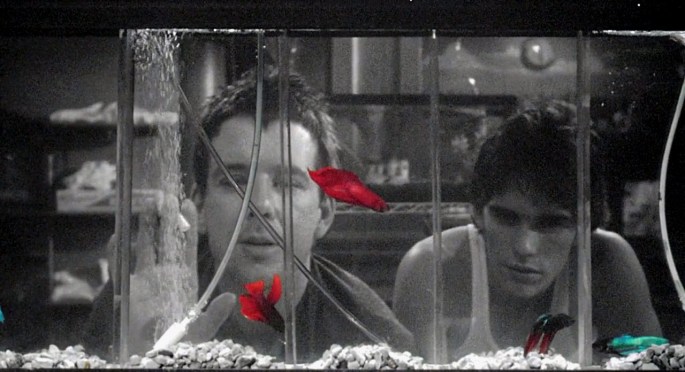

History remembers Francis Ford Coppola’s, Rumble Fish (1983) as a film that was booed by its audience when it debuted at the New York Film Festival and in turn was viciously crucified by North American critics upon general release. It’s too bad because it is such a dreamy, atmospheric film that works on so many levels. It is also Coppola’s most personal and experimental project — on par with the likes of Apocalypse Now (1979). From the epic grandeur of The Godfather films to the excessive Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Coppola has pushed the boundaries, both on-screen and off. He has almost gone insane, contemplated suicide, and faced bankruptcy on numerous occasions, but he always bounces back with another intriguing feature that is visually stunning to watch. And yet, Rumble Fish curiously remains one of Coppola’s often overlooked films. This may be due to the fact that it refuses to conform to mainstream tastes and stubbornly challenges the Hollywood system with its moody black and white cinematography and non-narrative approach.

Right from the first image Rumble Fish is a film that exudes style and ambiance. It opens on a beautiful shot of wispy clouds rushing overhead, captured via time lapse photography to the experimental, percussive soundtrack that envelopes the whole film. This creates the feeling of not only time running out, but also a sense of timelessness. Adapted from an S.E. Hinton novel of the same name, Rumble Fish explores the disintegrating relationship between two brothers, Rusty James (Matt Dillon) and the Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke). The older brother derives his name from his passion: stealing motorcycles for joyrides. The film begins with the Motorcycle Boy absent, perhaps gone for good, while Rusty James tries to live up to his brother’s reputation: to act like him, to look like him, and, ultimately, to be him. Rusty James’ brother is viewed as a legend in the town as he was the first leader of a gang and also responsible for their demise.

Much like Harry Lime in The Third Man (1949), the Motorcycle Boy is initially physically absent, but his presence is felt everywhere — from the shots of graffiti on walls and signs that read, “The Motorcycle Boy Reigns,” to the numerous times he is referred to by characters. This quickly establishes him as a figure of mythic proportions. When the Motorcycle Boy finally does appear — during a fight between Rusty James and local tough, Biff Wilcox (Glenn Withrow) — it is a dramatic entrance on a motorcycle like Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953). This appearance marks a significant change in the film. We begin to see the world through the eyes of the Motorcycle Boy, almost as if the whole film is taking place in his head.

Consequently, Rumble Fish is shot entirely in black and white to simulate his color blindness. We even begin to hear the world like he does: voices sound echoey, disembodied, with his own heartbeat threatening to drown everything else out. It is this existential worldview that makes the Motorcycle Boy a tragic character. The rest of the film explores his attempts to come to grips with this outlook and his relationship with Rusty James, who views him as a hero — a label that the older sibling has never been able to accept.

Coppola wrote the screenplay for Rumble Fish with Hinton on his days off from shooting The Outsiders (1982). As the filmmaker said in an interview, “the idea was [that] The Outsiders would be made very much in the style of that book, which was written by a 16-year old girl, and would be lyrical and poetical, very simple, sort of classic. The other one, however, Rumble Fish, which she wrote years later, was more adult, kind of Camus for teenagers, this existential story.” Coppola even went so far as to make the films back-to-back, retaining much of the same cast and crew. Warner Brothers was not happy with an early cut of The Outsiders and chose not to distribute Rumble Fish. Despite a lack of financing, Coppola completely recorded the film on video during two weeks of rehearsals in a former school gymnasium, encouraging his young cast to improvise.

Actual filming began on July 12, 1982 on many of the same Tulsa, Oklahoma sets used in The Outsiders. The attraction to Rumble Fish, for Coppola, was the “strong personal identification” he had with the subject matter: a young brother hero-worships his older, intellectually superior sibling. Coppola realized that the relationship between Rusty James and the Motorcycle Boy mirrored his own connection to his brother, August. It was an older, more experienced August who introduced Francis to film and literature. Coppola always felt like he was living in the shadow of his brother and saw the film as a “kind of exorcism, or purgation” of this relationship.

As always, Coppola assembled an impressive ensemble cast for his film. From The Outsiders, he kept Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Glenn Withrow, William Smith, and Tom Waits, while casting actors like Mickey Rourke and Vincent Spano who were overlooked for roles in the film for one reason or another. They fill out their roles admirably, but Mickey Rourke in particular, is mesmerizing as the Motorcycle Boy.

To get Rourke into the mindset of his character, Coppola gave him some books written by Albert Camus and a biography of Napoleon. “There’s a scene in there when I’m walking down the bridge with Matt; and I’d try and stylise my character as if he was Napoleon,” the actor remembers. The Motorcycle Boy’s look was patterned after Camus complete with trademark cigarette dangling out of the corner of his mouth — taken from a photograph of the author that Rourke used as a visual handle. He portrays the character as a calm, low key figure that seems to be constantly distracted as if he is in another world or reality. Rourke “Methodically” conceived the Motorcycle Boy as being “an actor who no longer finds his work interesting.” To this end, he uses subtle, little movements and often cryptic phrases that only he seems to understand.

This feeling is further enforced by the two brothers’ alcoholic father, played brilliantly by Dennis Hopper in a surprisingly low key performance. He describes the Motorcycle Boy perfectly when he says that “he is merely miscast in a play. He was born in the wrong era, on the wrong side of the river. With the ability to be able to do anything that he wants to do and finding nothing that he wants to do.” Rourke’s Motorcycle Boy is almost embarrassed by the myth that surrounds him, that threatens to drown him. He openly rejects it when he says, “I’m tired of all that Robin Hood, Pied Piper bullshit. You know, I’d just as sooner stay a neighborhood novelty if it’s all the same to you… If you’re gonna lead people, you have to have somewhere to go.” It is this reluctance to embrace his legendary reputation that gives the Motorcycle Boy an element of humanity that was not in the novel.

Not only did Coppola assemble a talented cast of actors, but he also gathered an impressive crew to create the images and the proper mood to compliment them. The striking black and white photography of the film’s cinematographer, Stephen Burum, lies in two main sources: the films of Orson Welles and German cinema of the 1920s. Welles’ influence is particularly apparent in one scene where the Motorcycle Boy and Steve bring a wounded Rusty James home. While Steve and Rusty James talk in the background, the Motorcycle Boy looms into a close-up, as if the lens were a mirror in which he was admiring himself. He is clearly a character who suffers from what one critic called, “fatal narcissism,” a trait common in many of Welles’ films. This deep focus shot (a favorite of Welles) shows how far removed the Motorcycle Boy is from his brother and from everyone. He is like a mirror, impenetrable and impossible to read as Steve observes, “I never know what he’s thinking.” This scene harkens back to Welles’ masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941), which used the deep focus technique to give characters that look of “fatal narcissism,” to live a doomed existence.

Before filming started, Coppola ran regular screenings of old films during the evenings to familiarize the cast and in particular, the crew with his visual concept for Rumble Fish. Most notably, Coppola showed Anatole Litvak’s Decision Before Dawn (1951), the inspiration for the film’s smoky look, and Robert Wiene’s Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) which became Rumble Fish‘s stylistic prototype. Coppola’s extensive use of shadows (some were painted on alley walls for proper effect), oblique angles, exaggerated compositions, and an abundance of smoke and fog are all hallmarks of these German Expressionist films. Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (1983), shot mainly in time-lapse photography, motivated Coppola to use this technique to animate the sky in his own film. The result is an often surreal world where time seems to follow its own rules.

Coppola envisioned a largely experimental score to compliment his images. He began to devise a mainly percussive soundtrack to symbolize the idea of time running out. As Coppola worked on it, he realized that he needed help from a professional musician. And so he asked Stewart Copeland, drummer of the musical group The Police, to improvise a rhythm track. Coppola soon realized that Copeland was a far superior composer and let him take over. The musician proceeded to record street sounds of Tulsa and mixed them into the soundtrack with the use of a Musync, a new device at the time, that recorded film, frame by frame on videotape with the image on top, the dialogue in the middle, and the musical staves on the bottom so that it matched the images perfectly. One only has to see Copeland’s evocative score matched with the film’s exquisite imagery to realize how well the musician understood Coppola’s intentions.

Rumble Fish is a rare example of a gathering of several talented artists whose collaboration under the guiding vision of a filmmaker results in a unique work of art. Why then, did the film receive such scathing reviews when it was released? The film alienated former head of production for Paramount, Robert Evans, who “remembers being shaken by how far Coppola had strayed from Hollywood. Evans says, ‘I was scared. I couldn’t understand any of it.'” Rumble Fish’s failure may have been due to the climate of American cinema at the time. The film was released in the early 1980s when art films and independent cinema were not as widely celebrated as they are now. Nobody was ready for a stylish black and white film with few big name stars and little sign of mainstream appeal. American critics and studio executives, on the whole, just did not “get it.”

It is a marvel that Rumble Fish was even made at all. Only Francis Ford Coppola’s unwavering determination and his loyal cast and crew could have made such a project possible. He had the clout and the resources to assemble such a collection of talented people to create a challenging film that acts as the cinematic equivalent of the novel by capturing its mood and tone perfectly. Every scene is filled with dreamy imagery that never gets too abstract but, instead, draws the viewer into this strange world. Coppola uses color to emphasize certain images, like the Siamese fighting fish in the pet store — some of the only color in the film — to create additional layers in this complex, detailed world.

With a few odd exceptions, Coppola has been content to merely rest on his laurels and reputation and crank out safe, formulaic films that lack any real substance or passion. Perhaps Coppola is tired from the numerous battles he has had with Hollywood studios over the years and simply does not have the energy to make the daringly ambitious films that he made during the ’70s and early ’80s. It is too bad, because Rumble Fish shows so much promise and creativity. Tossed off as a self-conscious art film, now that some time has passed, I see it as a movie clearly ahead of its time: a stylish masterpiece that is obsessed with the notion of time, loyalty, and family. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Coppola’s film is that it presents a world that refers to the past, present, and future while remaining timeless in nature.

UNFAITHFUL – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

Sometimes it’s frustrating being a Diane Lane fan. For an actress so talented, she appears in a lot of dreck. For every The Outsiders (1983) or A Walk on the Moon (1999), there are three or four Must Love Dogs (2005) type clunkers. Yet, she gamely plugs along, turning in consistently good performances in even the most routine films (Murder at 1600). With Unfaithful (2002), she finally found material that could challenge her by portraying a fascinatingly flawed character in a provocative film. It was a remake of Claude Chabrol’s 1968 film, La femme infidele and was directed by Adrian Lyne, a filmmaker not afraid to court controversy by bringing a European sensibility to sex and sensuality in films like 9½ Weeks (1986), Indecent Proposal (1993), and Lolita (1997). With Unfaithful, he proposed a simple yet intriguing premise: why would a woman with a successful, loving husband and nice child threaten this security with an illicit affair with another man? While his film ultimately conforms to clichéd thriller conventions, Lane transcends the material with a career-best performance that garnered her all kinds of critical accolades and awards, chief among them an Academy Award nomination.

Constance Sumner (Lane) has it all: Edward (Richard Gere), a handsome husband with a successful business in New York City, and Charlie (Erik Per Sullivan), an adorable son. They live in a beautiful house on a lake outside of the city. Not to mention Connie has a body most women her age would kill for. The worst you could say about Connie and Edward’s marriage is that it’s gotten routine. They obviously still love each other and have that familiar shorthand that couples do after living together for years. For example, one morning she notices that he’s wearing a sweater inside out and lets him know before he goes off to work. We first see her in the midst of domesticity, doing the dishes and getting Charlie ready for school. She’s loving and supportive towards her husband and child.

Diane Lane and Richard Gere play this sequence well and are quite believable as a married couple by the way they interact with each other. Lyne inserts little details to reinforce their comfortable domesticity, like how Connie stops the dog bowl from moving around as their pet hungrily chows down on his food – it’s a move that looks like she’s done many times over the years. It also didn’t hurt that Lane and Gere were paired up previously in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984) and while they didn’t have much chemistry together on that film, they at least had something to build on.

One particularly windy, blustery day, Connie goes into the city to run some errands and literally runs into a young man (Olivier Martinez) carrying an armful of books. They both go sprawling and she ends up scraping her knees. He invites her up to his apartment so that she can tend to her wounds and call for a taxi. His offer isn’t difficult for her to accept. He’s gorgeous looking and has a sexy French accent. Paul is a book dealer who just happens to look like fashion model – of course he does or how else are the filmmakers going to explain Diane Lane cheating on someone like Richard Gere? Paul is aloof and accommodating but when Connie goes off to use his telephone, he checks her out. The camera adopts his point-of-view, slowly moving up her long legs to her face. No one can quite make a trenchcoat look sexy like Lane does in this scene.

Paul startles Connie by gently placing an ice pack on her knee and first physical contact is made. The look she gives him, a sly smile, makes you wonder if it is at this moment that she first thinks about having an affair with this man. The extremely windy day that starts off this scene is a harbinger, an ominous warning of how turbulent Connie’s life will become once she accepts this man’s invitation. After this alluring encounter, Connie comes home to reality: toys lying around, the dog roaming around and her son watching television. Later, she and Edward try to make love but are interrupted by Charlie – the ultimate mood killer.

Home alone during the day, she checks out the book Paul gave her and inside is his business card. On an impulsive whim, she takes the train into the city and calls him on a pay phone. Paul invites her over and Connie accepts, turned on by the attention she is getting from this mysterious, attractive young man. Once there, he slyly puts the moves on her, taking off her coat so that his fingers brush up against her neck. Lane is excellent in this scene as she conveys the excitement her character feels being with this man, the apprehension of being unsure of what she’s doing, and the inner turmoil as you can tell that she’s trying to decide whether to leave or stay. Ultimately, Connie leaves and visits her husband at work, giving him a present out of the guilt she feels for seeing Paul.

She visits him again and he excites her in the way he looks and touches her. Paul looks at Connie in a very seductive way that makes her feel wanted and desired – something that she doesn’t feel with Edward. She has a moment of conscience where she tells Paul that what they are doing is a mistake, to which he replies, “There’s no such thing as a mistake. There’s what you do and what you don’t do.” Connie leaves and then comes right back to get her coat. Before she can say anything, Paul embraces here and literally sweeps her off her feet. Lyne does an interesting thing here. Instead of just showing their subsequent love scene, he breaks it up by intercutting Connie’s train ride home, juxtaposing her emotional reaction to what she’s done with the act itself. As he demonstrated with 9½ Weeks, Lyne certainly knows how to capture the erotic intimacy of a sex scene.

Lyne shows Paul gently touching Connie’s body, which is trembling in fear and excitement. The emotional turmoil that plays across Lane’s face is astounding as she displays a vulnerability that is quite raw. This gentle foreplay segues into something more primal as Connie attempts one more time to stop this and Paul tells her to hit him so that her aggressive passion that he knows lurks under her conflicted surface will take away her fear. It does as she pummels him and this gives way to passionate kisses as she hungrily devours him. This is intercut with Connie’s train ride home as she reflects on what she’s done. The range of emotions that play across her face as she replays it over in her mind is incredible to watch. She smiles to herself and her hand absently runs across her chest. Her mood darkens ever so gradually before lightening again as she smiles and then breaks out into a laugh. Finally, her face takes on a slightly sad expression. In only a few moments, she has run a whole gamut of emotions and pulls it off masterfully.

Edward has been married to Connie long enough to sense when something is off with her. Early on, he doesn’t have any definite indicator that something is amiss except for a possible small lie that she told him. But it’s enough for him to ask her one night if she loves him. Richard Gere asks Lane in such a way that your heart goes out to his character. He’s done nothing wrong while she’s off having an affair with another man.

Lyne orchestrates another fascinating montage that juxtaposes Connie spending time with Edward and her son at their home with her spending time with Paul in the city. She has fun with both men but in different ways. With Edward, she feels safe and secure in domesticity, and with Paul, she feels excited and passionate. Ultimately, she is looking for someone who can make her feel both safe and passionate. Connie’s affair emboldens her to take unnecessary risks, like kissing Paul in a public place and, by chance, one of the men (Chad Lowe) that works with her husband sees them.

As he demonstrated in both 9½ Weeks and Indecent Proposal, Lyne really knows how to photograph women and bring out their beauty. Unfaithful is no different as he does an incredible job of conveying Lane’s beauty, both naked (the scene where she takes a bath) and clothed (she can even make wearing a t-shirt and jeans look sexy). It is the way he lights her and the angles he uses that bring out her natural good looks. Lane has never looked or acted so well.

When Edward suspects that Connie isn’t being truthful with him yet again, he checks up on her excuse and finds out that she lied to him. To add further risk, when she’s in the city to meet Paul for another tryst, Connie runs into a friend of hers with a co-worker. Unable to ditch them, they all go out to lunch. Connie calls Paul and tells him what happened and he shows up. On the spur of the moment, they have sex in a bathroom stall. Lyne shows a playful side during this scene as he cuts between Paul and Connie’s brief but passionate bout of sex and Connie’s friend talking to her co-worker about how good Connie looks, which is rather obvious. As Edward’s suspicions grow, he decides to have Connie followed and what he finds out and how he acts on it, changes the entire complexion of the story and the film.

The longer the affair goes on, the more selfish Connie becomes and she loses sight of what’s important to her – Edward and Charlie. She has become addicted to her rendezvous with Paul as he consumes her thoughts to the point where she even gets jealous when she spots him with another woman. Connie becomes more desperate and her behavior more erratic as the affair continues.

Richard Gere has the thankless role of playing the spurned husband and he does a good job of eliciting sympathy early on. Edward may not be has handsome as Paul but, c’mon, it’s Richard Gere! The man has aged incredibly well and looks handsome no matter how many frumpy sweaters Lyne tries to put him in. Gere’s finest moment in Unfaithful is when his character confronts Paul. Edward starts off angry but Gere doesn’t chew up the scenery – it’s a slow burn as Edward questions Paul and then he gradually becomes unglued. Gere has to convey a wide spectrum of emotions in this scene and does so quite expertly. From that scene on, his character undergoes a very profound change and it is interesting to see how Gere plays it out.

After years of playing heroic roles in films like Judge Dredd (1995), Lane began to seek out projects that gave her the chance to play more flawed characters. In many respects, A Walk on the Moon was a warm-up for her role in Unfaithful. In that film, she played a 1960s housewife who gets caught up in the sexual revolution of the era and cheats on her husband with a good-looking traveling clothes salesman. Whereas her character’s motivation was clearer in that one, it is more ambiguous in Unfaithful. In fact, Lyne cast Lane based on her work in A Walk on the Moon in which he found her to be “very sympathetic and vulnerable.”

During the production, Lyne fought with 20th Century Fox over the source of the affair. Executives felt that there needed to be a reason while the director believed that chance played a large role. Early drafts of the screenplay featured the Sumners with a dysfunctional sexual relationship and the studio wanted them to have a bad marriage with no sex so there would be more sympathy for Connie. Lyne and Gere disagreed and the director had the script rewritten so that the Sumners basically had a good marriage. He said, “The whole point of the movie was the arbitrary nature of infidelity, the fact that you could be the happiest person on Earth and meet somebody over there, and suddenly your life’s changed.”

When it came time to assemble the crew for this film, Lyne asked director of photography Peter Biziou, with whom he had made 9½ Weeks, to shoot Unfaithful. After reading the screenplay, Biziou felt that the story lent itself to the classic 1.85:1 aspect ratio because there was often “two characters working together in frame.” During pre-production, Biziou, Lyne and production designer Brian Morris used a collection of still photographs as style references. These included photos from fashion magazines and shots by prominent photographers.

Initially, the story was set against snowy exteriors but this idea was rejected early on and the film was shot from March 22 to June 1, 2001 with Lyne shooting in sequence whenever possible. Much of the film was shot in Greenwich Village and Lyne ended up incorporating the city’s unpredictable weather. During the windstorm sequence where Connie first meets Paul, it rained and Lyne used the overcast weather conditions for the street scenes.

Lyne also preferred shooting in practical interiors on location so that, according to Biziou, the actors “feel an intimate sense of belonging at locations,” and use natural light as much as possible. A full four weeks of the schedule was dedicated to the scenes in Paul’s loft which was located on the third floor of a six-story building. Biziou often used two cameras for the film’s intimate sex scenes so as to spare the actors as little discomfort as possible. For example, Olivier Martinez wasn’t comfortable with doing nudity. So, to get him and Lane in the proper frame of mind for the sex scenes, Lyne showed them clips from Five Easy Pieces (1970), Last Tango in Paris (1972), and Fatal Attraction (1987). The two actors hadn’t met before filming and didn’t get to know each other well during the shoot, a calculated move on Lyne’s part so that their off-camera relationship mirrored the one of their characters.

Lyne tested his cast and crew’s endurance by using smoke in certain scenes to enhance the atmosphere. According to Biziou, “the texture it gives helps differentiate and separate various density levels of darkness farther back in frame.” Lyne used this technique on all of his films; however, on a set where cast and crew were filming 18-20 hour days, it got to be a bit much. Gere remembered, “Our throats were being blown out. We had a special doctor who was there almost all the time who was shooting people up with antibiotics for bronchial infections.” Lane even used an oxygen bottle for doses of fresh air between takes.

The last 25 minutes of Unfaithful slides dangerously into formulaic thriller territory, threatening to derail what had been up to that point an engrossing drama about an illicit affair. Why did Lyne feel the need to go in this direction? Did the studio influence his decision and mandate that he incorporate more commercial elements? Lane and Gere do their best to keep things on track and it’s a credit to their abilities that they keep us interested in what is happening to their characters as they transcend the material. In some respects, Unfaithful is a horror film for married couples or for people in some kind of long-term relationship as it shows the ramifications of cheating on one’s spouse. The tragic thing is that all of this could have been avoided if Connie and Edward just talked to each other openly and honestly about how they felt about things. After all, communication is the key to a successful marriage or any meaningful relationship. As Unfaithful shows, lies only complicate things and drive people apart. It’s a harsh lesson that Connie and Edward learn the hard way.

Batman Vs Superman: Dawn Of Justice – A Review by Nate Hill

Batman Vs. Superman: Dawn Of Justice. Wow. Where to even start. What a symphony of scorched earth heroics, a two and a half hour maelstrom of thundering action, introspective gloom and very current vibes of apocalyptic dread. I’m not sure if I was watching an entirely different film from some of these bitter bottomed critics who are maiming it with inaccurately nasty reviews. Balls to them. Zach Snyder should be proud of this achievment, for in the face of both ruthless odds and rabid fans who would make any one of us piss down our legs at the thought of ‘getting it right’, he has mounted a titanic epic of a superhero flick, hitting all the right notes and fuelling both casual moviegoers and salivating super fans with a rekindled love for comic book films. A much welcomed grit and violent edge creeps into the proceedings here, a tone which Snyder has a passion for and is incredibly deft with. We begin with a visually arresting opening credit sequence, which Snyder previously perfected to hair raising brilliance in Watchmen, a ten minute opus set to Bob Dylan. Here he inter cuts shots of young Bruce Wayne, both discovering the prophetic swarm of bats and on the fateful night of his parents murder, a sequence done over a thousand times in film, but never quite with the inventive flair used here. We then arrive with adult Bruce (Ben Affleck) in Metropolis right as it’s being ripped to shreds by the Def Jam smackdown match of Superman (Henry Cavill) and Zod (Michael Shannon). There’s eerie shades of 9/11 as Bruce darts through the ashen rubble, attempting to save the employees in one of his towers. One senses the fear and rage in Wayne right off the bat (pun intended). He glowers in seething fury at the man of steel, primally threatened and haunted all over again by loved ones he couldn’t save a second time around. This film addresses the ludicrous amount of destruction that Superman wrought upon Metropolis in several ways. Political nerve endings are fried as Senate and State alike get hostile towards the god in the red cape. No one is more aggressive than Batman, though. This brings me to Affleck as Batman. Without a doubt my favourite cinematic incarnation of the caped crusader, and his debonair counterpart to date. Yes, even more so than Bale. Nolan’s The Dark Knight is still tops for me, but the portrayal of Batman by Bale didn’t strike as harmonious a chord with me as Affleck. It just didn’t feel like pure Batman, it was real world Batman. Affleck feels much more rooted in the comics, and God damn it all if he isn’t the most savage, violent Bats to come our way, well… ever. I’ve always been bothered by the nagging fact that Batman refuses to kill. Even in in a beatdown he could easily inadvertently cause death, so why bother trying? Here, he doesn’t go out of his way to deliberatly kill, but he sure has no problem brutally breaking bones and stabbing his adversaries without an iota of faux-noble hesitation. That’s the kind of Batman I want to see. Fuming, fired up and full of rage demons that erupt into fantastic action scenes. One sequence involving a room full of thugs is just jaw dropping and probably my favourite sequence of the film, even over the titular smackdown with Superman. There’s an earthy, simplistic take to him as well, with a modest suit that gives nods to Frank Miller and even Batman: The Animated Series. He is by far the elemental force that the character should be, and the part of the film that I connected with most. I hope he gets his standalone film real soon. Henry Cavill has grace and intuition as Superman, and a surprisingly earthly aura as Clark Kent, in a fit about Batman’s vigilante tactics. He’s the outsider here, an orphaned deity truly trying to do his best in a world that often shuns him in fear. He was never my favourite superhero, or even on the list, but Cavill combined with Snyder make him a force to be reckoned with, and a hero I can get behind. The two eventually meet in a remarkably choreographed clash of the titans, a duel that really only lasts a few minutes and isn’t central theme, which raises questions in my head about the first part of that title. Their fight is composed of Batman’s hard hitting, blunt force physicality pitted against Superman’s fluid, elegent invincibility which is satisfyingly put to the test by the appearance of a certain green mineral we all know about. The James Cameron-esque suit Batman wears for the fight is a grinding wonder that looks like it weighs a metric ton and could level buildings alongside the man of steel. The combat feels urgent, from the gut and roars into action perfectly. Of course, that isn’t where the fireworks stop, but I ain’t sayin any more than that. Gal Gadot is truly wonderful as Wonder Woman, I also can’t wait for her solo outing, and wish she’d been in the film more. Her much talked about entrance is the definition of crowd pleasing, and will make you cheer in approval, which I did out loud. She’s endlessly gorgeous, and has the toughness to go along with it, a great casting decision by anyone’s tally. Jesse Eisenberg wowed me as a young, jittery Lex Luthor, in what is probably the most clinically insane portrayal thus far. Forget bumbling Gene Hackman and hammy Kevin Spacey, this guy seals it for me. There’s a true madness to his Lex, which when given enough money and resources can have cataclysmic results. It’s a villain to remember, and Eisenberg exudes palpable danger from every pore, his psychopathic sheen of logic barely shrouding the mania beneath. Jeremy Irons is a more restrained, jaded Alfred who is still unconditionally supportive of Wayne, but is reaching the end of his rope which is tethered to pure world weariness. He gets some of the only humerous bits of the film, albeit of dry, brittle variety. Amy Adams is reliably terrific, her eyes pools of perception that mirror the horror and spectacle of the events through the mind of a human, with every ounce of nerve and courage as those around her that have superpowers, or expensive toys. Diane Lane is weathered wisdom and maternal compassion as Martha Kent, nailing her scenes with the small town, kindhearted patience that a film this noisy deserves, tipping the scales to provide occasional serenity in the eye of the hurricane. Kevin Costner makes a brief appearance in one of the films numerous and often confusing dream sequences. He was a highlight in Man Of Steel, and brings the same baleful, gruff adoration here, in a wonderful but brief scene with Clark. Laurence Fishburne is another source of rare humour as the perpetually exasperated Perry, CEO of the Daily Planet. Aggravated and cheeky, he commands every frame he’s in and had me chuckling no end. Holly Hunter has forged a career of playing no nonsense hard asses, here a ballbreaking US Senator here who shares a moment of distilled intensity with Luthor proving that Superhero films can have some of the best written dialogue. Harry Lennix makes great use of said writing too as the steely Secretary Of Defense. Callan Mulvey and Scoot McNairy are memorable in supporting turns. Listen hard for Patrick Wilson and Carla Gugino, and look for a certain ocean dwelling dude in the briefest of moments. Jeffrey Dean Morgan also has a cameo that’s almost too good to be true. Hans Zimmer and Junkie XL, who was so top notch with Mad Max: Fury Road, combine efforts for a score that knocks it out of the park and several miles further. Batman has a soul rousing battle cry of an overture, with subtle shades of Zimmer’s work on the Nolan films, built upon to give us something truly unique and fitting for the character. Lex Luthor is accompanied by a fitful cacophony of strings that sound like the Arkham Asylum charity orchestra having a collectively unnerving seizure. My favourite riff though I think is for Wonder Woman, a deviously disarming jaunt that strays from the grandiose, baroque theme and feels wickedly subversive, getting you just so pumped for her character. Zimmer’s work on Interstellar made it my top score of 2014, because he leapt out of the box of his usual tricks and gave us something we’d never heard from him before. Here he shreds that box with ingenuity and creative output, a varied, explosive piece that assaults your ears splendidly. My one concern with the film was a dream sequence midway through concerning Batman, and anyone who’s seen the film knows what I’m talking about. I’m sure comic book fans have some point of reference or context regarding it, but the casual viewer doesn’t, and a little more explaining would have been nice. I will say though it showcases Batman in an entirely new light which took me off guard nicely. This is what a superhero movie should be, plain and simple. Big, bold, audacious, stirring and full of high flying action, dastardly villains, conflicted heroes clashing like the ocean tides and a sense of pure adventure. Forget what the critics are saying, this one comes up aces in all categories and is a perfectly wonderful start to the stories of a group of characters that I look forward to seeing in many a film to come. Especially Affleck’s Batman.

The Cotton Club: A Review by Nate Hill

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club is every bit as dazzling, chaotic and decadent as one might imagine the roaring twenties would have been. it’s set in and revolves around the titular jazz club, conducting a boisterous, kaleidoscope study of the various dames, dapper gents, hoodlums, harlots and musicians who called it home. Among them are would be gangster Dixie Dwyer (a slick Richard Gere), Sandman Williams (Gregory Hines), a young Bumpy Johnson (Laurence Fishburne) and renowned psychopathic mobster Dutch Schultz (a ferocious James Remar). Coppola wisely ducks a routine plot line in favor of a helter skelter, raucous cascade of delirious partying, violence and steamy romance, a stylistic choice almost reminiscent of Robert Altman. Characters come and go, fight and feud, drink and dance and generally keep up the kind of manic energy and pizazz that only the 20’s could sustain. The cast is positively stacked, so watch for appearances from Nicolas Case, Bob Hoskins, Diane Lane, John P. Ryan, James Russo, Fred Gwynne, Allen Garfield, Ed O Ross, Diane Venora, Woody Strode, Giancarlo Esposito, Bill Cobbs, Sofia Coppola and singer Tom Waits as Irving Stark, the club’s owner. It’s a messily woven tapestry of crime and excess held together by brief encounters, hot blooded conflict and that ever present jazz music which fuels the characters along with the perpetual haze of booze and cigarette smoke. Good times.