I wanted to give RIPD chance, I really did. But it’s such a shameless ripoff of Men In Black that most of it just constituted one big eye roll from me. It’s not an outright knockoff, but it just uses the unmistakable blueprint of MIB and runs with it as if it were it’s own organic idea. The veteran wiseass, the young hotshot, the clandestine otherworldly law enforcement syndicate, googly, goopy special effects, it’s all there and just feels stale these days, but for a few saving graces. Jeff Bridges is an undeniable charmer as Roy, an undead wild west super cop who is tasked with retrieving runaway souls hiding out down on earth, and capturing them for return to the great beyond, here pictured as the penultimate vision of nightmarish beaurocracy that seems oddly derived from Beetlejuice (huh). When Boston cop Ryan Reynolds is betrayed and murdered by his corrupt scumbag of a partner (a skeezy Kevin Bacon) he’s recruited by Proctor (Mary Louise Parker, all business and loving it) to join Roy in bringing “deados” back upstairs. The two don’t get along, as newly paired cops in movies always behave, and the banter only really works from Bridges’s side. He’s a hoot as crotchety old Roy, while Reynolds plays it a bit too serious, especially in scenes with the wife he left behind (Stephanie Szostak). The film earns it’s one inspired subplot when we see the human avatars the pair use to move about the earthly plane: Bridges is a knockout blonde chick (Marissa Miller), and Reynolds an elderly Chinese man played by the seemingly immortal James Hong. If they spent more time on terrifically funny ideas with potential like that and less on special effects that look like something out of the Garbage Pail Kids, they might have been on to something worthwhile. But alas, most of the film is spent on a whirlwind of silly slapstick and big gross weird things that are in no way engaging. There’s a few slap dash deado hunts, including a brief turn from Robert Knepper as one that is lured out of hiding with Chinese food (what in the..), and a big sky vortex yawner of a finale where evil Bacon tries to wreak havoc on earth. Most of the time it’s just a snooze though, save for the few times the clouds part and we get something fresh, usually from either Bridges or those to damned hilarious avatars. Shame.

Tag: Jeff Bridges

Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King: A Review by Nate Hill

Tragic. Uplifting. Comical. Bittersweet. One of a kind. Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King takes on mental illness by way of a fantastical approach, an odd mix on the surface, but totally fitting and really the only way to put the audience inside a psyche belonging to one of these beautiful, broken creatures. Sometimes an unlikely friendship springs from a tragedy, in this case between a scrappy ex radio DJ (Jeff Bridges) and a now homeless, mentally unstable ex professor of medieval history (Robin Williams). Bridges was partly responsible for an unfortunate incident that contributed to William’s condition, and feels kind of responsible, accompanying him on many a nocturnal odyssey and surreal journey through New York City, an unlikely duo brought together by the whimsical cogs of fate that seem to turn in every Gilliam film. Williams is a severely damaged man who sees a symbolic ‘Red Knight’ at every turn, and seeks a holy grail that seems to elude him at every turn. Bridges is down to earth, if a little aimless and untethered, brought back down from the clouds by his stern, peppy wife (Mercedes Ruehl in an Oscar nominated performance). They both strive to help one another in different ways, Williams to help Bridges find some redemption for the single careless act that led to violence, and Bridges assisting him on a dazed quest through the streets to find an object he believes to be the holy grail, and win over the eccentric woman of his dreams (Amanda Plummer). In any other director’s hands but Gilliam’s, this story just wouldn’t have the same fable-esque quality. Straight up drama. Sentimental buddy comedy. Interpersonal character study. There’s elements of all, but the one magic ingredient is Gilliam, who is just amazing at finding the way to truth and essential notes by way of the absurd and the abstract. Watch for fantastic work from Michael Jeter, David Hyde Pierce, Kathy Najimy, Harry Shearer, Dan Futterman and a quick, uncredited Tom Waits as well. The hectic back alleys and silhouetted trellises of NYC provide a sooty canvas for Gilliam and his troupe to paint a theatrical, psychological and very touching tale of minds lost, friendship found and the past reconciled.

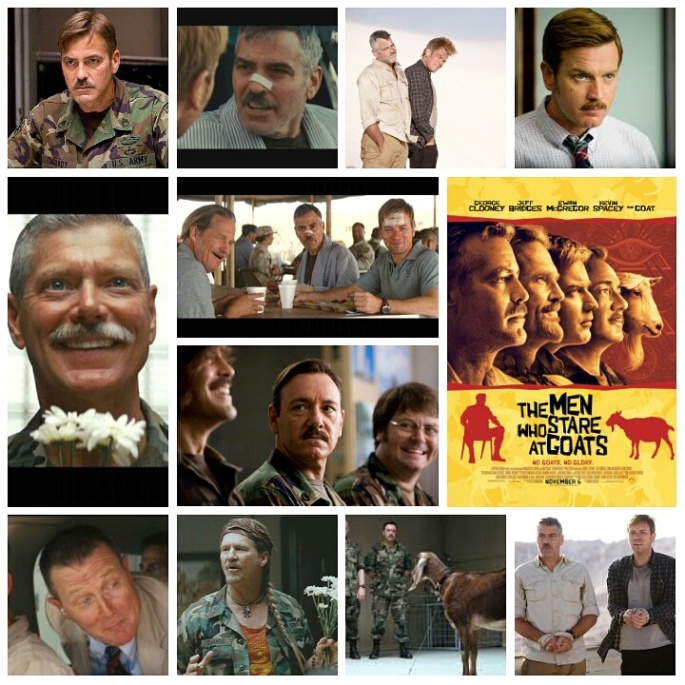

The Men Who Stare At Goats: A Review by Nate Hill

Stephen Lang Week: Day 2

There’s a scene early on in The Men Who Stare at goats where hapless General Dean Hopgood (Stephen Lang) attempts a platform 9 & 3 quarters style sprint towards a solid wall, in attempt to use ‘psychic abilities’ he is being taught at a hush-hush military base. He smashes headlong into it, and in the most deadpan drawl, mutters “damn” in all seriousness. This one moment sort of sums up the absurd vibe that thrums throughout the whole film. It’s kind of like a Coen Brothers thing; you either get it or you don’t. This film isn’t quite as hilarious as it’s sister, Burn After Reading, but damn if it doesn’t try, and come out with some really weird and memorable stuff. It’s colorful hogwash that the cast sells with the enthusiasm of a drunken used car salesman, and speaking of cast, wow there are a lot of heavy hitters playing in the sandbox here. George Clooney, in yet another of his patented lovable goof roles, plays Lyn Cassidy, a former US Army nutjob who claims to have been a part of a clandestine program called the New Earth Army, employing paranormal powers in their missions. Bemused journalist Ewan McGregor is shanghai’d into following him on a mad goose chase to find out if any of his stories are true, but mostly just to babysit him, as he’s kind of a walking disaster. Ineptitude reaches a breaking point when we meet pseudo hippie Bill Django, played by Jeff Bridges who channels every other oddball role he’s done for maximum effect. Bill headed up the program until he got stymied by opposing official Larry Hooper (Kevin Spacey), a tight ass skeptic with no patience for such silliness. In fact, one must have a huge tolerance for such silliness to sit through this, and a sense of humour just south of normal to appreciate what it has to offer. I have both, and greatly enjoyed it, despite being thoroughly bewildered. Watch for Stephen Root, Glenn Moreshower, Rebecca Mader, Nick Offerman and good old Robert Patrick in a cameo as some sort of vague spy dude. A clown show to rival a high school play, no doubt, and I mean that as a compliment.

THE MEN WHO STARE AT GOATS – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

George Clooney is one of those versatile actors that can easily go back and forth between big budget studio films like Ocean’s Eleven (2001) and smaller, more personal independent films like Good Night, and Good Luck (2005). One gets the feeling that given his preference, he’d much rather make the latter than the former but he’s smart enough to know that doing the occasional studio film gives him the opportunity to make smaller films. One glance at the cast list for The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009) and you would assume that it was a studio film with the likes of Clooney, Jeff Bridges, Ewan McGregor, and Kevin Spacey involved. It’s the offbeat premise, however, that could only come from an indie film.

Inspired by Jon Ronson’s non-fiction bestseller of the same name, The Men Who Stare at Goats follows the misadventures of Bob Wilton (McGregor), an investigative journalist in search of a major story to cover. He stumbles across a secretive wing of the United States military called The New Earth Army, created to develop psychic powers in soldiers. These include reading the enemy’s thoughts, passing through walls, and yes, killing a goat by staring at it. While doing a story about a man (Stephen Root) who stopped the heart of his pet hamster with his mind for a local newspaper in Ann Arbor, Wilton finds out that this man used to be part of a top secret military unit of psychic spies in the 1980s. At least, that’s what he claims.

Understandably skeptic about the man’s abilities, Wilton learns about the former leader of the unit, Lyn Cassady (Clooney), “the most gifted psi-guy” who now runs a dance studio. After a co-worker dies suddenly and his wife leaves him for his editor, Wilton interprets these incidents to be a wake-up call and travels to the Middle East to cover the war. By chance (or is it?), while staying at a hotel in Kuwait, he runs into Cassady. This self-proclaimed Jedi Warrior (?!) tells Wilton about Project Jedi, a hush-hush assignment that cultivated Super Soldiers with super powers. Cassady’s technique for tapping into these powers involves drinking alcohol and listening to the music of classic rock band Boston.

Wilton learns all about this elite unit that combines “the courage and nobility of the Warrior” with “the spirituality of the Monk,” and follows in the footsteps of “the great Imagineers of the past”: Jesus Christ, Lao Tse Tung and Walt Disney. Wilton convinces Cassady to allow him to tag along during his mission in Iraq and the rest of the film plays out as a quirky road movie cum satire of war films.

George Clooney is quite good as the clearly bat-shit crazy Cassady. The actor plays the role seriously but you can see that insane glint in his eyes. It’s impressive how he is able to say some of his character’s ridiculous dialogue with a straight face. Clooney gets maximum laughs by playing it straight and is also not afraid to act silly when the situation calls for it. And it does in one of the film’s funniest set pieces during a flashback where Cassady’s New Age commanding officer (Bridges) loosens up the unit by having them spontaneously dance to “Dancing with Myself” by Billy Idol. It’s pretty funny seeing a bunch of uniformed soldiers, Clooney included, dancing their asses off.

Clooney is surrounded by a very impressive supporting cast. Jeff Bridges plays a peace-loving high ranking soldier, sort of the Dude if he had been drafted instead of dropping out of society. Kevin Spacey is the black sheep of the unit and jealous of Clooney’s powers. Meanwhile, Ewan McGregor is the naive reporter and audience surrogate. They all get their moments to show their stuff but the film really belongs to Clooney and his seriously wacky character.

After making serious political films like Syriana (2005) and Good Night, and Good Luck, it’s nice to see Clooney starring in a political satire that is funny but still has something to say as it shows the absurdity of the war in Iraq. This is evident in a scene where Cassady and Wilton narrowly escape a firefight between two competing security firms. The Men Who Stare at Goats falls under the truth is stranger than fiction category as it presents a story populated by eccentric characters and tall tales, some of which might be true. Regardless, it is an entertaining film with a wonderfully oddball sense of humor in the same vein as other memorable war satires like M*A*S*H (1970), Catch 22 (1970) and Three Kings (1999). Don’t be put off by the setting. Although it takes place in Iraq, The Men Who Stare at Goats is not weighed down by the baggage of this war.

TRON – A REVIEW BY J.D. LAFRANCE

When Tron came out in 1982, it was intended to be a visually stunning parable against the abuse of powers by computers and technology. More than thirty years later, the film plays more like a nostalgic ode to the early 1980s than a simple good vs. evil morality tale. Tron evokes the heady days when video games like Pac-Man, Defender and Centipede ruled the arcades and when it seemed like everyone owned a Commodore 64 or an Atari 2600 – the eight track of personal computing. It also anticipated the proliferation of CGI special effects and was not a big hit back in the day but its influence is widespread – it enjoys a loyal cult following today.

Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) is a hot shot computer programmer turned computer hacker after being fired three years ago by ENCOM corporate big wig, Ed Dillinger (David Warner). To add insult to injury, the executive stole a series of video games that Flynn created and transformed them into wildly popular and profitable products, chief among them Space Paranoids – much to the young programmer’s chagrin. Flynn can prove true authorship of the games but only if he can gain direct access to ENCOM’s mainframe. Enter ex-girlfriend Laura (Cindy Morgan) and her current beau, Alan (Bruce Boxleitner) – both disgruntled employees at ENCOM – who give Flynn the access he needs to find out the truth. However, the corporation’s artificial intelligence, the tyrannical Master Control Program, discovers what Flynn is doing and uses a high tech laser to digitize the troublesome hacker and transport him inside the computer world.

This is where Tron really begins to get interesting as writer/director Steven Lisberger creates a flashy, neon-drenched world, a cybernetic version of Social Darwinism where lowly computer programs must participate in gladiatorial battles against the Master Control’s ruthless minions. These involve games where opponents throw glowing discs at each other or, in another game, hurl a ball of energy at one another. If either one of these things hits someone, they are killed or de-rezzed – slang for deresolution. Even though the computer effects are primitive by today’s standards, back then they were considered ahead of their time. There is a certain clunky charm to the effects that makes Tron all that more endearing to its fans. The look of the computer world is all blacks and dark blues, which is in nice contrast to the vivid neon red and blue of some of the characters and vehicles that inhabit it.

Undeniably, the coolest sequence in the film is the light cycle race where Flynn, Ram (Dan Shor) and Tron take on three of the MCP goons. It involves futuristic vehicles made out of energy and that leave behind a solid trail that one uses to block in their opponent and destroy them. The action is fast-paced and exciting to watch with dynamic visuals. The computer world is beautifully realized in vivid detail that immerses one fully and is obviously a large part of the film’s appeal. Lisberger adopts a pretty simple color scheme of predominantly primary colors. Tron is one of those rare examples where style over substance works. The computer world that Lisberger and his team worked so hard to create is rich in detail. It also plays on our romantic notions of what really goes on inside our computers – not a collection of microchips and circuit boards but a vast world where programs fight each other for survival. It’s no wonder that visionary science fiction writer, William Gibson once commented in an interview that the cyberworld in Tron is how he envisioned the cyberspace in his own novels.

The film’s genesis began in 1976 when Lisberger, then an animator of drawings with his own studio, looked at a sample reel from a computer firm called MAGI (Mathematical Applications Group, Inc.). At the time, he was researching technology in the late 1970s. Shortly afterwards, Atari came out with Pong and he was immediately fascinated by them. He wanted to do a film that would incorporate these electronic games. According to Lisberger, “I realized that there were these techniques that would be very suitable for bringing video games and computer visuals to the screen. And that was the moment that the whole concept flashed across my mind.” He was frustrated by the clique-ish nature of computers and video games and wanted to create a film that would open this world up to everyone.

Lisberger and his co-producer Donald Kushner borrowed against the anticipated profits of their 90-minute animated television special, Animalypmics to develop storyboards for Tron. They moved to the west coast in 1977 and set up an animation studio to develop Tron. Originally, the film was conceived to be predominantly an animated film with live-action sequences acting as book ends. The rest would involve a combination of computer generated visuals and back-lit animation. Lisberger planned to finance the movie independently by approaching several computer companies but had little success. One company, Information International, Inc., was receptive. He met with Richard Taylor, a representative, and they began talking about using live-action photography with back-lit animation in such a way that it could be integrated with computer graphics.

Lisberger and Kushner took their storyboards and samples of computer-generated films to Warner Bros., MGM and Columbia – all of whom turned them down. Lisberger spent two years writing the screenplay and spent $300,000 of his own money marketing the idea for Tron and had also secured $4-5 million in private backing before reaching a standstill. In 1980, Lisberger and Kushner decided to take the idea to Disney, which was interested in producing more daring productions at the time. However, Disney executives were uncertain about giving $10-12 million to a first-time producer and director using techniques that, in most cases, had never been attempted.

The studio agreed to finance a test reel which involved a flying disc champion throwing a rough prototype of the discs used in the film. It was a chance to mix live-action footage with back-lit animation and computer generated visuals. It impressed the executives at Disney and they agreed to back the film. The script was subsequently re-written and re-storyboarded with the studio’s input. At the time, Disney rarely hired outsiders to make films for them and Kushner found that he and his group were given a less than warm welcome because “we tackled the nerve center – the animation department. They saw us as the germ from outside. We tried to enlist several Disney animators but none came. Disney is a closed group.”

One the reasons why the cyberspace in Tron is so striking is because of the creative brain trust assembled to help realize it. Futuristic industrial designer Syd Mead, legendary French comic book artist Jean “Moebius” Giraud, and high-tech commercial artist Peter Lloyd served as special visual consultants. Mead designed most of the vehicle designs (including Sark’s aircraft carrier, the light cycles, the tank and the solar sailer). Moebius was the main set and costume designer for the film. Lloyd designed the environments. However, these jobs often overlapped with Moebius working on the solar sailer and Mead designing terrain, sets and the film’s logo. The original Program character design was inspired by the main Lisberger Studios logo, a glowing body builder hurling two discs. CGI had been used in films before, most notably in Westworld (1973) and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), but it was used much more extensively in Tron. In order to pull it off, four of the United States’ foremost computer graphics houses produced the computer imagery for the film. They invented the computer techniques and created the visual effects in approximately seven months. More than 500 people were involved in the post-production work, including 200 inker and hand-painters in Taiwan.

Jeff Bridges brings a playful energy to the film both in the real world – like when he breaks into ENCOM – and in the computer world, like when he gets acclimatized to his new surroundings. Tron is the no-nonsense hero while Flynn provides comic relief. We are introduced to Flynn in his environment – the video arcade that he owns, beating the world record score for Space Paranoids, one that he invented but was stolen from him. Now, he plays the game and the only profits he sees from it are the quarters that kids put in it. Bridges brings an engaging, boyish charm to the role as is evident in the way he gleefully circumvents ENCOM security and then proceeds to sneak in so that he can find and use an unattended computer terminal. There are the little touches, like when Flynn sneaks on ahead and hides from Laura, that keep the mood light and fun, just before our hero is zapped into the computer world.

In the real world, Tron’s alter ego, Alan is a bespectacled, slightly bookish programmer who is frustrated by the lack of access he has to his company’s computer system. Bruce Boxleitner plays these two contrasting roles quite well. He knows he’s the straight man to Bridges’ charismatic goofball Flynn. We meet his character as he tries to access a high level of security so that he can run his Tron program, an independent security program that would act as a watchdog to the company’s MCP computer. There is a cut to a long shot and we see that Alan’s cubicle is one of hundreds – impersonal and he is treated as an insignificant cog in a massive corporation. Interestingly, the corporation’s name is ENCOM, which eerily foreshadows another evil empire, but in the real world – ENRON.

Amazingly, Tron wasn’t even nominated for a special effects Academy Award because “the Academy thought we cheated by using computers,” Lisberger remembers. However, his film and the world he and his team created captivated a small group of moviegoers. A loyal cult following developed around Tron over the years. The film may have not captured the public consciousness when it first came out but it has since developed a loyal following that loves it dearly. In many respects, Tron is a snapshot of the early ’80s when video games were just starting to take off, but it also was a harbinger of things to come. It paved the way for the elaborate computer graphics we see in movies like The Matrix (1999) and the new Star Wars movies. However, Tron warns that we cannot rely totally on computers to do everything because in doing so we run the risk of losing our humanity. I always imagine Flynn going on to become Bill Gates or maybe Steve Jobs.

Amazingly, Tron wasn’t even nominated for a special effects Academy Award because “the Academy thought we cheated by using computers,” Lisberger remembers. However, his film and the world he and his team created captivated a small group of moviegoers. A loyal cult following developed around Tron over the years. The film may have not captured the public consciousness when it first came out but it has since developed a loyal following that loves it dearly. In many respects, Tron is a snapshot of the early ’80s when video games were just starting to take off, but it also was a harbinger of things to come. It paved the way for the elaborate computer graphics we see in movies like The Matrix (1999) and the new Star Wars movies. However, Tron warns that we cannot rely totally on computers to do everything because in doing so we run the risk of losing our humanity. I always imagine Flynn going on to become Bill Gates or maybe Steve Jobs.

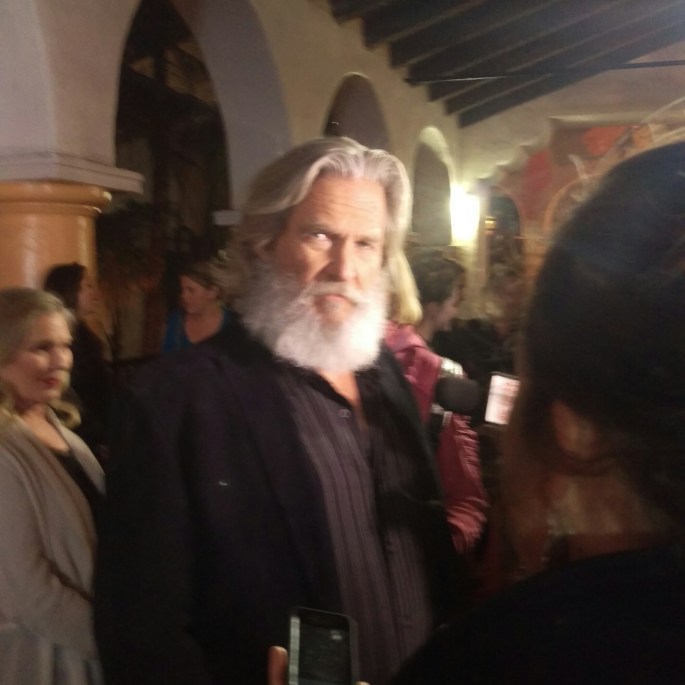

31st Santa Barbara International Film Festival Opening Night: THE LITTLE PRINCE

Opening the 31st Santa Barbara International Film Festival was the new film by Mark Osborne, THE LITTLE PRINCE. The film completely honored Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s legendary novella. SBIFF’s director, Roger Durling, introduced the film, spoke of how much the novella means to him, and then he joyfully introduced Santa Barbara’s favorite son, donning an incredibly glorious beard, Jeff Bridges.

The voice cast is one of the most eclectic and brilliant voice casts ever. Bridges headlines as the Aviator, Rachel McAdams as the Mother, Paul Rudd as Mr. Prince, Marion Cotillard as the Rose, James Franco as the Fox, Benico Del Torro as the Snake, Bud Cort as the King, Paul Giamatti as the Academy Teacher, Riley Osborne as the Little Prince, Mackenzie Foy as the Little Girl, Ricky Gervais as the Conceited Man, and Albert Brooks as the Business Man.

The film itself has a wonderfully unique animation style that was a merger of stop motion looking animation and clean and crisp animation that was masterfully fastened together by Osborne.

The film was as funny as it was sweet and struck the perfect balance of the importance of child’s development of daring to be yourself and adult oriented entertainment.

STEPHEN HOPKINS’ BLOWN AWAY — A REVIEW BY NICK CLEMENT

Back in the summer of 1994, there were three big action films to hit the marketplace: Speed, True Lies, and sandwiched in between, was the underrated Blown Away, which suffered the worst box office fate of the bunch but still delivered more than enough thrills and excitement to qualify as an action-packed blast of unpretentious entertainment. This movie is so much fun in an old-school, traditional manner (it just FEELS, in a great way, like an MGM movie), shot with lots of style by director Stephen Hopkins (Predator 2, The Ghost and the Darkness) and acted with intense ferocity by Jeff Bridges and Tommy Lee Jones, as a Boston bomb squad officer and a mad Irish bomber respectively. Jones is running wild on the streets of Boston, blowing up anything and everything he can find, all in an effort to exact revenge on his old friend Bridges, who both went through IRA/terrorist issues which are dealt with in black and white flashback. Bridges is the noble cop who always seems to know which wire to cut – the blue one or the red one. While the plotting is mostly predictable, the film knows exactly what it’s doing with its numerous action scenes, and it must be pointed out, that the film features the SINGLE GREATEST DONE-FOR-REAL EXPLOSION ever captured on film. There’s no debating this. I fucking LOVE movie explosions. I’ve made it a point to STUDY them throughout my life. This one is top-dog. When Jones’ old shipyard boat goes kablooey at the climax, you literally can’t believe what you’re watching and that the two fearless stuntmen weren’t killed or burned to death. The image has REAL camera shake, glass windows in downtown buildings were blown out, and total radio silence in and around Boston Harbor was kept for 10 miles so no interference could occur with the destruction of the balsa wood ship. Peter Levy’s cinematography is terrific all throughout, and the brisk editing keeps the pace moving fast. Kino has just released an excellent special edition Blu-ray of this extremely fun, throw-back type action thriller that was more old-fashioned than audiences may have been expecting. Hopkins provides a great, info-filled commentary, and the picture transfer is very crisp and clean, retaining that awesome, slick-and-gritty 90’s film stock look, with that final explosion looking all sorts of epic and awesome in full 2.35:1 widescreen (previous DVD releases were non-anamorphic). Alan Silvestri’s score is appropriately bombastic and thoroughly exciting. Forest Whitaker, Suzy Amis, Ruben Santiago-Hudson, John Finn, and Lloyd Bridges all offer memorable support. Cuba Gooding Jr. has literally 30 seconds of screen time in one scene. Jay Roach (Meet the Parents) got original story credit!

Episode 8: Brad Bird’s TOMORROWLAND, Tod Williams’ THE DOOR IN THE FLOOR, Top Five Jeff Bridges and Kim Basinger

Episode 8 is now live! We discuss the current theatrical release of Brad Bird’s TOMORROWLAND, and our feature film of the week, Tod Williams’ THE DOOR IN THE FLOOR as well as our top five performances of Jeff Bridges and Kim Basinger! Enjoy everyone!

THE DOOR IN THE FLOOR 2004 Dir. Tod Williams – A Review by Frank Mengarelli

“Don’t ever, not ever, never, never, never, open the door in the floor.”

Simply put, THE DOOR IN THE FLOOR is one of the best films from the previous decade. It is small, intimate and arousing. Set in present day in New England, the film follows a young man, Eddie, who is set to graduate from a prestigious prep school, Exeter Academy, the same school where Ted Cole (Jeff Bridges) went, and his two deceased teenage sons went as well. The intent of Eddie’s summer is meant to be spent interning for Ted, Ted was a novelist who became a popular children’s writer, and Eddie is an aspiring writer himself. As the summer moves along, revelations are made, tragedy, old and new are summoned, and a love affair between Ted’s wife Marion (Kim Basinger) and Eddie formulates.

This film is tough. Pain, love, loss and isolation surface almost immediately. Marion never got over the death of their two sons, and Ted has transformed the pain into raising their young daughter Ruth (Elle Fanning) and working on a new children’s book featuring his recurring characters, Thomas and Timothy which are hauntingly named after their two sons who died.

Jeff Bridges gives him most vicious and turbulent performance as Ted. He is an alcoholic philanderer who emotionally uses people, and softly degrades them. Basinger gives her finest performance as the broken and stoic Marion, who has never fully recovered from the loss of their two sons, and who uses Eddie sexually as a vessel to channel her pain.

There are few, but the scenes between Bridges and Basinger are absolutely beautiful. These two characters are so broken, and everything they have been through together was only sustainable by their love for each other. Even though it is not expressed physically, nor shown at all, you can feel how pure it is, how undying it is.

So many films are made about love, and very few can express it the way THE DOOR IN THE FLOOR does. Pure love at times messy, filled with pain, and beautifully tragic and this film is an absolute visual and musical interpretation of that love. The film is beautifully shot by Terry Stacey, and remarkably scored by Marcelo Zaruos. The film’s score is as important as any other aspect of the film, it does not arbitrarily show up and is not easily ignored. It is designed to provoke an emotional reaction in a scene of a film that is layered with joyous yet heartbreaking emotion.

The film’s title is taken from Ted’s most famous children’s book, which upon watching him read it to an audience, and seeing the dark drawings of the book (which Bridges drew himself), it is perhaps the most intense children’s book ever written. The film begs a question to the audience. Have you opened your own door in the floor? Will you open your own door in the floor? Will you face your own desires, your fears? Will you come to terms with the realities of everything that you love, everything that you hate? It is simple for anyone to open the door in the floor, but not many can withstand what comes through it.