“What I’d like to do today is get your version of what happened,” says a mild-mannered, middle-aged attorney. “Oh? You mean the truth,” replies a rather small, aging Chinese man who identifies himself as bus driver, Egg Shen (Victor Wong). The attorney remains skeptical as his potential client calmly describes his belief in Chinese black magic, and other supernatural phenomenon. As if to prove his point, the man holds up his hands so that they are parallel to one another. Suddenly, small bolts of blue electricity begin to flow from each palm, much to the attorney’s amazement and Shen’s bemusement. “That was nothing,” Shen states. “But that’s how it always begins. Very small.” And with this intriguing, tell-me-a-scary-story teaser, John Carpenter’s film, Big Trouble in Little China (1986), takes us on a ride into the heart of ancient Chinese lore and mythology.

Carpenter, always the maverick director with a knack for exploring offbeat subject matter (see They Live and In the Mouth of Madness), created a film that simultaneously parodies and pays homage to the kung-fu film. This often-maligned genre is given a new level of respectability that is rarely seen in Hollywood. Gone are the ethnic slurs, the insulting stereotypes and that annoying quasi-Chinese music that always seems to accompany representations of Asians in past mainstream features. Big Trouble takes great care in presenting funny and intelligent characters without caring whether they are Chinese or not. What is of paramount importance to Carpenter is telling a good story. He has created an entertaining piece of fantasy that manipulates the conventions of the action film with often-comical results.

From the engaging prologue, Big Trouble takes us back to the beginning of our story with the first appearance of truck driver Jack Burton (Kurt Russell), a good-natured, fast-talking legend in his own mind. When he and his buddy, Wang Chi (Dennis Dun), go to the airport to pick up the latter’s future bride arriving from China, a mix-up occurs. Wang’s bride-to-be is kidnapped by The Lords of Death, a local gang of Chinese punks, and the duo quickly find themselves immersed in the middle of an ancient battle of good vs. evil with immortality hanging in the balance. This struggle takes place deep in the heart of the Little China neighborhood of San Francisco with Burton and Wang Chi taking on David Lo Pan (James Hong), “The Godfather of Little China.” Even Egg Shen appears to help our heroes and provide them with the means to stop the evil that threatens not only Little China, but of course, the whole world.

Big Trouble in Little China was originally written as a period Western set in the 1880s with Jack Burton as a cowboy who rides into town. Producer Paul Monash bought Gary Goldman and David Weinstein’s screenplay but after a reading he found that it was virtually unfilmable due to the bizarre mix of Chinese mythology and the Wild West setting. He had the two first-time screenwriters do a rewrite, but Monash still didn’t like it. “The problems came largely from the fact it was set in turn-of-the-century San Francisco, which affected everything — style, dialogue, action.” The producer decided against having Goldman and Weinstein do additional rewrites because they didn’t want to upgrade the story to a contemporary setting and felt that they had done their best.

Keith Barish and Monash brought in W.D. Richter, a veteran script doctor (and director of cult film, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai) to extensively rewrite the script. Almost everything in the original screenplay was discarded except for Lo Pan’s story. “I realized what it needed wasn’t a rewrite but a complete overhaul. It was a dreadful screenplay. This happens often when scripts are bought and there’s no intention that the original writers will stay on.” Richter’s template for his draft was Rosemary’s Baby (1968). “I believed if, like in Rosemary’s Baby, you presented the foreground story in a familiar context — rather than San Francisco at the turn-of-the-century, which distances the audience immediately — and just have one simple remove, the world underground, you have a much better chance of making direct contact with the audience.” Richter was having a hard time getting his own scripts made into movies so he tried sneaking in his own eccentric ideas into other people’s projects. “It’s often easier to take an idea that they bring to you and try to pass it through your sensibility. If you’re honest up front, you get license to work with material you wouldn’t get them to look at if it was your own story.”

John Carpenter had wanted to do a film like Big Trouble in Little China for some time. Even though it contains elements of an action / adventure / comedy / mystery / ghost story / monster movie, it is, in the filmmaker’s eyes, a kung-fu film. “I have dug the genre ever since I first saw Five Fingers of Death in 1973. I always wanted to make my own kung-fu film, and Big Trouble finally gave me the excuse to do just that.” Barish and Monash offered Carpenter the movie in July of 1985. He had read the Goldman/Weinstein script and deemed it “outrageously unreadable though it had many interesting elements.” After reading Richter’s script he decided to direct. Carpenter loved the off-the-wall style of Richter’s writing and coupled with his love of kung-fu films, it is easy to see why he jumped at the opportunity to make Big Trouble.

The two filmmakers had crossed paths before when Carpenter rewrote Richter’s screenplay, The Ninja, a big-budget martial arts epic, for 20th Century Fox. In fact, Richter and Carpenter had both attended University of Southern California Film School from 1968 to 1971. “Rick and I went through all three production classes together. We each had our own crews, so we never actually collaborated on a film.” Carpenter made his own additions to Richter’s screenplay, which included strengthening Gracie Law’s role and linking her to Chinatown, removing a few action sequences (due to budgetary restrictions), and eliminating material deemed offensive to Chinese Americans. Carpenter was disappointed that Richter didn’t receive a proper screenwriting credit on the movie for all of his hard work. A ruling by the Writer’s Guild of America gave Goldman and Weinstein sole credit.

Problems began to arise when Carpenter learned that the next Eddie Murphy vehicle, The Golden Child (1986), featured a similar theme and was going to be released near the same time as Big Trouble. Ironically, Carpenter was asked by Paramount to direct The Golden Child. “They aren’t really similar. Originally, Golden Child was a serious Chinese, mystical, very sweet, very nice film. But now they don’t know whether to make it funny or serious.” However, as both films went into production, Carpenter’s views of the rival production became increasingly bitter. “Golden Child is basically the same movie as Big Trouble. How many adventure pictures dealing with Chinese mysticism have been released by the major studios in the past 20 years? For two of them to come along at the exact same time is more than mere coincidence.” To avoid being wiped out by the bigger star’s film, Carpenter began shooting Big Trouble in October 1985 so that 20th Century Fox could open the film in July 1986 — a full five months before Golden Child’s release. This forced the filmmaker to shoot the film in 15 weeks with a $25 million budget.

To achieve the efficiency that he would need for such a shoot, Carpenter surrounded himself with a seasoned crew from his previous films. He reunited with three long-time collaborators, line producer Larry J. Franco (Starman), production designer John Lloyd (The Thing), and cinematographer Dean Cundey. The cameraman had worked with Carpenter on his most memorable features: Halloween (1978), Escape from New York (1981), and The Thing (1982). The director wanted as many familiar faces on board because “the size and complexity are so vast, that without it being in dependable, professional hands, it could have gone crazy…So I went back to the guys who had been with me in the trenches before on difficult projects.”

Carpenter and Cundey had parted company before Starman due to “attitude problems.” Cundey says it was due to scheduling conflicts, but Carpenter has said that they had problems while working on The Thing. However, when Big Trouble came along, Carpenter met Cundey in Santa Barbara one weekend. “His attitude about survival in the [movie] business coincided with my own. We had a really good time, so we decided to work together again.”

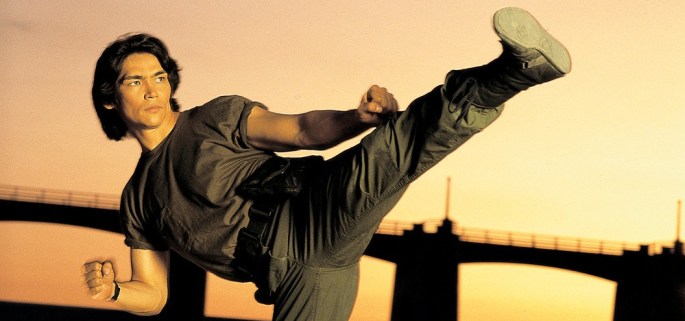

Big Trouble also saw Carpenter re-team with his old friend, actor Kurt Russell who has appeared in several of the director’s films, most notably Escape From New York and The Thing. At first, Carpenter didn’t see Russell as Jack Burton. He wanted to cast a big star like Clint Eastwood or Jack Nicholson to compete with Golden Child‘s casting of Eddie Murphy. However, both Eastwood and Nicholson were busy and Fox suggested Russell because they felt that he was an up-and-coming star. The actor remembered reading the script and thinking that it “was fun, but I was soft on the character. I wasn’t clear how to play it. There were a number of different ways to approach Jack, but I didn’t know if there was a way that would be interesting enough for this movie.” After Carpenter and Russell began to go over the script, the character started to take shape. The role was a nice change for Russell as Carpenter remembers, “Kurt was enthusiastic about doing an action part again, after playing so many roles opposite ladies recently. So off we went.”

After watching Big Trouble it’s impossible to see anybody else as Jack Burton. Russell perfectly nails the macho swagger of his character: he’s a blowhard who’s all talk, totally inept when it comes to any kind of action and yet is still a likable guy. It is the right mix of bravado and buffoonery, a parody of the John Wayne action hero much in the same way Russell made Escape From New York’s Snake Plissken a twisted homage to Clint Eastwood. Russell said, at the time, that he “never played a hero who has so many faults. Jack is and isn’t the hero. He falls on his ass as much as he comes through. This guy is a real blowhard. He’s a lot of hot air, very self-assured, a screw-up. He thinks he knows how to handle situations and then gets into situations he can’t handle but some how blunders his way through anyhow.” Russell showcases untapped comedic potential that ranges from physical pratfalls to excellent comic timing in the delivery of his dialogue. One only has to look at his scene with Wang and the elderly Lo Pan to see Russell’s wonderful comic timing. No one before or since Big Trouble has been able to tap into Russell’s comedic potential as well as Carpenter does in this movie.

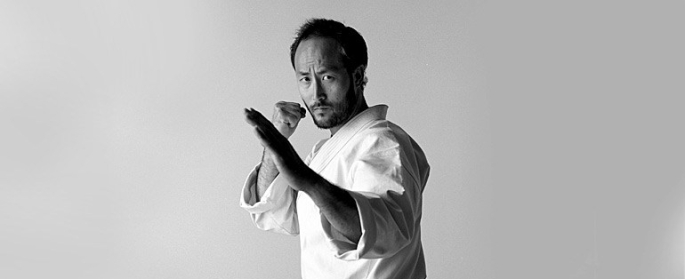

By many of the actors’ accounts, Carpenter is a director open to suggestions and input from everyone involved. Dennis Dun’s character starts off as the sidekick of Big Trouble and ends up accomplishing most of the film’s heroic tasks while the initial hero, Jack Burton, becomes the comic relief. Prior to Big Trouble, Dun’s only other film role was a small part in Michael Cimino’s Year of the Dragon (1985) but he was a veteran of more than twenty plays. Carpenter liked the actor in Cimino’s film and met with him twice before casting him in Big Trouble. Even though shooting began only a few days after Dun was cast, the action sequences weren’t hard for the actor who had “dabbled” in martial arts training as a kid and done Chinese opera as an adult.

Dun enjoyed the freedom he had on the set. “John gave me a great deal of leeway to develop my character and pretty much let me do what I wanted. He just encouraged me to be as strong as I could. He gave me a lot of freedom.” This freedom results in a very strong performance from Dun who holds his own against a veteran actor like Russell. Dun remembers that he and Russell shared the same approach to acting. “We never really talked about the scenes. We would come in that day to shoot a scene, and we would just do it. A large part of it was working off each other, just looking in each other’s eyes and taking each other’s energy and running with it.” The chemistry between the two characters is one of the many endearing qualities of Big Trouble as evident from numerous scenes, most notably the one where Wang Chi bets Jack that he can split a beer bottle in half and the scene where the two men attempt to break into Lo Pan’s building to rescue Wang’s fiancée.

The studio pressured Carpenter to cast a rock star in the role of Gracie Law, Jack Burton’s love interest and constant source of aggravation. For Carpenter there was no question, he wanted Kim Cattrall. The studio wasn’t crazy about the idea because at the time Cattrall was primarily known for raunchy comedies like Porky’s (1981) and Police Academy (1984). “I told them we needed an actress, and I enjoyed the way Kim wanted to play the character. She blended in well with the film’s style.” Cattrall plays Gracie as a pushy, talkative lawyer who acts as the perfect foil for deflating Burton’s macho ego at every opportunity.

Big Trouble’s script cleverly avoids the trap of reducing her role to a screaming prop by having Gracie take an aggressive part in the action. “Actually,” Cattrall said in an interview, “I’m a very serious character in this movie. I’m not screaming for help the whole time. I think humor comes out of the situations and my relationship with Jack Burton. I’m the brains and he’s the brawn.” There’s a great give and take between her and Russell. Their characters make for an entertaining screwball comedy couple: he’s always on the make while she constantly fends off his obvious advances. This was Carpenter’s intention. He saw the characters in Big Trouble like the ones “in Bringing Up Baby or His Girl Friday. These are very 1930s, Howard Hawks people.” Listen to how Jack and Gracie talk to each other — it’s a very rapid-fire delivery of dialogue that is reminiscent of Hawks’ comedies.

Production designer John Lloyd designed the elaborate underground sets and re-created Chinatown with three-story buildings, roads, streetlights, sewers and so on. This was necessary for the staging of complicated special effects and kung-fu fight sequences that would have been very hard to do on location. For the film’s many fight scenes Carpenter “worked with my martial arts choreographer, James Lew, who literally planned out every move in advance. I used every cheap gag – trampolines, wires, reverse movements and upside down sets. It was much like photographing a dance.”

Another refreshing aspect of Big Trouble is the way it is immersed in authentic Chinese myths and legends. Carpenter explains: “for example, our major villain, Lo Pan, is a famous legend in Chinese history. He was a ‘shadow emperor,’ appointed by the first sovereign emperor, Chan Che Wong. Lo Pan was put on the throne as an impersonator, because Chan Che Wong was frightened of being assassinated. Then, Lo Pan tried to usurp the throne, and Chan Che Wong cursed him to exist without flesh for 2,000 years, until he can marry a green-eyed girl.” Big Trouble could have easily made light of Chinese culture, but instead mixes respect with a good dose of fun.

Big Trouble also places Asian actors in several prominent roles, including Victor Wong and Dennis Dun who is the real hero of the story, as opposed to Kurt Russell’s character who is a constant source of comedy. “I’ve never seen this type of role for an Asian in an American film,” Dun commented in an interview, “I’m Chinese in the movie, but the way it’s written, I could be anybody.” Big Trouble crushes the rather derogatory Charlie Chan stereotype by presenting interesting characters that just happen to be Chinese. Carpenter also wanted to avoid the usual cliché soundtrack. “The other scores for American movies about Chinese characters are basically rinky tink, chop suey music. I didn’t want that for Big Trouble. I wanted a synthesizer score with some rock ‘n’ roll.”

As if sensing the rough commercial road that the film would face, Russell felt that it would be a hard one to market. “This is a difficult picture to sell because it’s hard to explain. It’s a mixture of the real history of Chinatown in San Francisco blended with Chinese legend and lore. It’s bizarre stuff. There are only a handful of non-Asian actors in the cast.” Unfortunately, mainstream critics and audiences did not care about this radical reworking of the kung-fu film. Opening in 1,053 theaters on July 4, 1986, Big Trouble in Little China grossed $2.7 million in its opening weekend and went on to gross $11.1 million in North America, well below its estimated budget of $25 million.

Big Trouble came out before the rise in popularity of Hong Kong action stars like Jackie Chan, Jet Li and Chow Yun-Fat, and filmmakers like John Woo and Wong Kar-Wai. Mainstream audiences weren’t ready for this kind of movie. Despite being promoted rather heavily by 20th Century Fox, Big Trouble disappeared quickly from theaters. Bitter from having yet another movie of his snubbed by critics and ignored by audiences, Carpenter swore off the big studios. He learned the hard way that working with them meant compromising his art in order to advance his career. Carpenter laid it all out in an interview a year later: “everybody in the business faces one truth all the time — if your movie doesn’t perform immediately, the exhibitors want to get rid of it. The exhibitors only want product in their theaters which makes money. Quality has nothing to do with it.” Years later, he said, “The experience [of Big Trouble] was the reason I stopped making movies for the Hollywood studios. I won’t work for them again. I think Big Trouble is a wonderful film, and I’m very proud of it. But the reception it received, and the reasons for that reception, were too much for me to deal with. I’m too old for that sort of bullshit.”

Big Trouble in Little China has stood the test of time. It was rediscovered on home video where it has become a celebrated cult film with a dedicated audience. It has since become one of the most beloved films in John Carpenter’s career and with good reason. It is a fun, clever movie that still holds up today and remains one of the finest examples of cinema as pure entertainment.

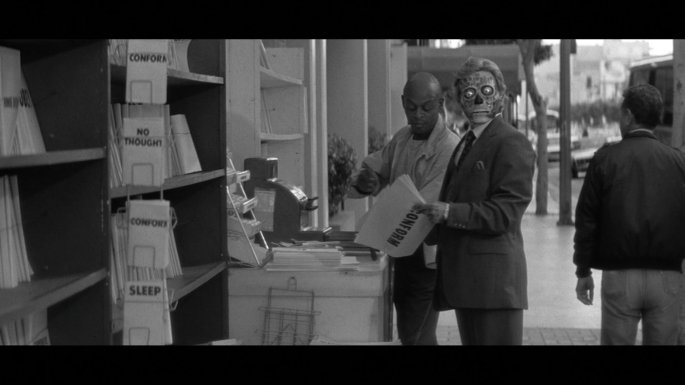

Carpenter sees the commercial failure of his film as a result of “people who go to the movies in vast numbers these days [who] don’t want to be enlightened.” It’s a shame because They Live is far from being an overtly preachy film. On the contrary, it is always exciting and entertaining first, and a scathingly social satire second. However, the director sees the real tragedy to be the lack of humanity in society. “The real threat is that we lose our humanity. We don’t care anymore about the homeless. We don’t care about anything, as long as we make money.” If They Live is about anything, it’s a strong indictment against the capitalist greed that was so fashionable in the 1980s. It’s sentiment that still exists. This makes Carpenter’s film just as relevant today as it was back in 1988.

Carpenter sees the commercial failure of his film as a result of “people who go to the movies in vast numbers these days [who] don’t want to be enlightened.” It’s a shame because They Live is far from being an overtly preachy film. On the contrary, it is always exciting and entertaining first, and a scathingly social satire second. However, the director sees the real tragedy to be the lack of humanity in society. “The real threat is that we lose our humanity. We don’t care anymore about the homeless. We don’t care about anything, as long as we make money.” If They Live is about anything, it’s a strong indictment against the capitalist greed that was so fashionable in the 1980s. It’s sentiment that still exists. This makes Carpenter’s film just as relevant today as it was back in 1988.