The 1970s saw the rise of the Movie Brats, a collection of filmmakers that had grown up watching and studying films. They made challenging films that reflected the times in which they were made and were revered by cineastes as much as some of the actors appearing in them. Directors like William Friedkin, Francis Ford Coppola, Hal Ashby and Martin Scorsese made intensely personal films that blended a European sensibility with American genre films. However, the one-two punch of Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) and the failure of expensive passion projects like New York, New York (1977) and Heaven’s Gate (1980) ended these directors’ influence and saw the rise of producers like Joel Silver, Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, and movie star-driven blockbusters in the 1980s and beyond. It got harder and harder for the Movie Brats to get their personal projects made. Most of them went the independent route, making films for smaller companies like Orion and doing the occasional paycheck gig with a Hollywood studio.

For years, Scorsese had been trying to fund a personal project of his own – an adaptation of The Last Temptation of Christ. It was a tough sell and he ended up making After Hours (1985) and The Color of Money (1986) as a way of keeping busy while he tried to get Last Temptation made. At the time of The Color of Money much was made of it being Scorsese’s first movie star-driven film and some critics and fans of the director felt that he was selling out. It would not only be promoted as a film starring Paul Newman and Tom Cruise (and not as a Scorsese film), but was a sequel (something that the director was never fond of doing) of sorts. Newman had been interested in reprising his famous role of “Fast” Eddie Felson from The Hustler (1961) for some time but he had never met the right person for the job – that is, until he met Scorsese.

The Color of Money begins twenty-five years after the events depicted in The Hustler and we find that Eddie (Newman) is enjoying a comfortable existence as a savvy liquor salesman with his bar owner girlfriend Janelle (Helen Shaver) and occasionally fronting a pool hustler. His current investment, a cocaine addict named Julian (played with just the right amount of sleazy arrogance by John Turturro), is getting roundly beaten by a young turk named Vincent (Tom Cruise) who catches Eddie’s attention with his “sledgehammer break.” He becomes fascinated watching Vincent play and his cocky behavior between shots, like how he works the table. Eddie also watches the dynamic between Vincent and his girlfriend Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). What really catches his attention is not just Vincent’s raw talent but also his passion for the game. He’s even willing to play Julian after he’s won all of the guy’s money because he just wants his “best game.”

There’s a nice bit where Eddie tests Carmen’s skill as Vincent’s manager, exposing her lack of experience and schooling her on the basics of pool hustling in a beautifully written monologue by Richard Price that Newman nails with the ease of a seasoned pro. We get another healthy dose of Price’s authentic streetwise dialogue in the next scene where Eddie takes Vincent and Carmen out for dinner and continues to school his potential protégés: “If you got an area of excellence, you’re good at something, you’re the best at something, anything, then rich can be arranged. I mean rich can come fairly easy.” The scene is also nicely acted as Tom Cruise plays the cocky upstart with just the right amount of arrogant naiveté without being a typical goofball. As Eddie puts it, “You are a natural character. You’re an incredible flake,” but tells him that he can use that to hustle other players. The ex-pool player lays it all out for the young man: “Pool excellence is not about excellent pool. It’s about becoming something … You gotta be a student of human moves.” And in a nice bit he proves it by making a bet with them that he’ll leave with a woman at the bar. Of course, he knows her but it certainly proves his point. This is a wonderful scene that begins to flesh out Vincent and establish how much he and Carmen have to learn and how much Eddie has since The Hustler.

The young man is a real piece of work – brash, directionless but with raw talent. It is clear that Eddie sees much of his younger self in Vincent and decides to take the young man under his wing and teach him “pool excellence” by taking him and Carmen on the road. It’s an opportunity to make some money while also getting back Eddie’s passion for playing pool. The Color of Money proceeds to show the three of them on the road for six weeks, getting ready for an upcoming nine-ball tournament in Atlantic City. Of course, there are the predictable bumps in the road as Vincent’s impulsive knack for showing off costs them money and Eddie feels like the young man’s not listening to him. It’s a formula we’ve seen used in countless films but Scorsese does everything he can visually to keep things interesting, especially in the dynamic way he depicts the numerous games of pool, the use of music (for example, one game is scored to “Werewolves of London” by Warren Zevon) and the actors that play some of the opponents along the way, like a young Forest Whitaker as a skilled player that manages to hustle and beat Eddie at pool.

However, it is the camerawork by veteran cinematographer Michael Ballhaus that impresses the most. He and Scorsese depict each game differently, employing a variety of techniques, like quick snap zooms in and out, and floating the camera gracefully over the pool table or gliding around it. He even has the camera right on the pool table following the balls around. The camera movement and editing rhythm of each game is dictated by the mood and intensity of each match, like the grandiose techniques employed when Vincent shows off during a game of pool. As he revels in his own showboating moves, the camera spins around him as if intoxicated by his bravado. However, much like the chaotic pool hall brawl in Mean Streets (1973), the camera movement goes nowhere symbolizing the futility of Vincent’s actions. Sure, he beat the top guy at that pool hall but in doing so scared off an older player that had much more money.

While The Color of Money was made fairly early on in Tom Cruise’s career, his relative inexperience actually suits his character. His youthful energy mirrors Vincent’s. It is his job to come across as an arrogant flake of a human being, which he does quite well (too well for some who were unimpressed with his performance). Cruise has always been an actor that performs better surrounded by more talented and experienced people and with the likes of Paul Newman acting opposite him and Scorsese directing, it forces the young actor to raise his game. One imagines he learned a lot on the job much like Vincent does in the film. Scorsese knew exactly what he was doing when he cast Cruise and got a solid performance out of him. In the late ‘80s, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio acted in a series of high profile roles like The Abyss (1989), The January Man (1989) and this film. She’s given the thankless job of the girlfriend role but manages to make the most of it. One gets the feeling that Carmen is a fast learner and smarter than Vincent. She is much like Eddie in understanding the business side of pool hustling.

Naturally, Newman owns the film, slipping effortlessly back into Eddie’s skin after more than 20 years and it’s like he never left. The scenes between him and Cruise are excellent as the headstrong Vincent bounces off of the world-weary Eddie. Over the course of the film something happens to the elder pool player. As he tells Vincent at one point, “I’m hungry again and you bled that back into me.” We see that youthful spark fire up in Eddie again after so many years dormant and Newman does a fantastic job conveying that. While many felt that his Academy Award for the performance he gives in The Color of Money was really a consolation prize for a career of brilliant performances, this does a disservice to just how good he is in this film and how enjoyable it is to watch him get to work with someone like Cruise and Scorsese, watching how their contrasting philosophies towards acting and filmmaking co-exist in this film. There is an energy and vitality that Cruise brings and Newman feeds off of it and Scorsese captures it like lightning in a bottle.

When Paul Newman read Walter Tevis’ sequel to The Hustler it made him wonder what “Fast” Eddie Felson would be doing now and wanted to revisit the character. He had seen Raging Bull (1980) and was so impressed by it that he wrote a letter to Scorsese complimenting him on such a fine piece of work. The director was just coming off of After Hours and was attached to several projects, including Dick Tracy, with Warren Beatty, a fantasy film entitled Winter’s Tale, Gershwin, with a screenplay written by Paul Schrader, and Wise Guy, a book about the New York mafia written by Nicholas Pileggi. However, they all took a backseat when Newman invited him to direct a sequel to The Hustler. The actor had been working on it for a year with a writer. Scorsese was interested but didn’t like the script Newman showed him because it was “a literal sequel. It was based on at least some familiarity with the original.” Scorsese felt like he couldn’t be involved with the project if he didn’t have some input on the original idea of the script.

Scorsese wanted to go in a different direction and brought in a new screenwriter, novelist Richard Price who had written The Wanderers and also a script for the director based on the film Night and the City (1950). Scorsese liked the script because it had “very good street sense and wonderful dialogue.” For The Color of Money, Price and Scorsese’s concept was basically what became the film, exploring the director’s preoccupation with redemption but with what Newman saw as “recapturing excellence, having been absent from it, and then witnessing it in somebody else.” Newman liked it and Price and Scorsese came up with an outline and began rewriting the script. Price studied pool players and wrote 80 pages of a script. They took it to Newman and got his input. By the end of nine months, Price and Scorsese decided to make the film with Newman.

For Scorsese this was the first time he had ever worked with a star of Newman’s magnitude. “I would go in and I’d see a thousand different movies in his face, images I had seen on that big screen when I was twelve years old. It makes an impression.” As a result, Scorsese and Price made the mistake of writing for themselves when they should have tailored the script to suit Newman and his image, or as Scorsese later said, “we were making a star vehicle movie.” The actor wanted to explore aging and the fear of losing his “pool excellence.” He also wanted the character of Minnesota Fats, played so memorably by Jackie Gleason in The Hustler, to return but Price couldn’t get the character to fit into the script. He and Scorsese even presented a version of the script with Fats in it to Gleason but he “felt it was an afterthought,” said Scorsese.

It was Newman that suggested Cruise for the role of Vincent to Scorsese. The young actor had met Newman before when auditioning to play his son in Harry & Son (1984). Scorsese cast Cruise before Top Gun (1986) had come out but he was a rising movie star thanks to Risky Business (1983). He had seen the young actor in All the Right Moves (1983) and liked him. The project was initially at 20th Century Fox but they didn’t like Price’s script and didn’t want to make it even with Cruise and Newman attached. Eventually, it went to Touchstone Pictures.

Newman was not fond of improvising on the set and suggested two weeks of rehearsals before filming. Scorsese wasn’t crazy about this and found them “aggravating. You are afraid that you are going to say ridiculous things, and the actors feel that way too.” However, he agreed to it and brought in Price so that he could make changes to the script. Fortunately, everyone felt secure in character and with each other. Price and Scorsese didn’t have the film’s ending resolved and felt that they had written themselves into a corner. The studio wanted them to shoot the film in Toronto but Scorsese felt that it was too clean and chose Chicago instead. Both Cruise and Newman did all their own pool playing with the former being taught how to do specific shots that he played in the film with the exception of one, which would have taken two additional days to learn and Scorsese didn’t want to spend the time. Cruise had dedicated himself to learning how to play pool: “All I had in my apartment was a bed and a pool table.” He worked with his trainer and the film’s pool consultant Mike Sigel for months before shooting started.

Some Scorsese fans marginalize The Color of Money as one of his paycheck films – the first he did for the money – and while it may not have the personal feel of a film like Taxi Driver (1976), it still has its merits, a strong picture that fits well into the man’s body of work. I would argue that it is one of his strongest films stylistically with some truly beautiful, often breathtaking camerawork capturing all the nuances of playing pool: the energy and vitality of the game is there without sacrificing any of the story or the characters. This film also shows how a director like Scorsese can take a hired gun project and make it his own. It looks, sounds and, most importantly, feels like one of his films and not a commercial studio picture. Others must have agreed as the film not only became Scorsese’s most financially successful film at the time but a critical hit as well.

The director proved to the studios that he could deliver the goods at the box office while to himself he was still able to invest the film with some of his own personal touches. Ultimately, The Color of Money is about Eddie’s redemption and rekindling the spark he had in The Hustler before the screws were put to him. As with many sports movies, the story builds towards the climactic big game or, in the case of this film, the big tournament but Price’s script offers a slight twist in that Eddie’s victory is a hollow one and the real one is at the very end when his love for playing pool has finally come back completely. He is reinvigorated and excited about where his life and game will go from here and this is summed up beautiful in the film’s last line – “I’m back.”

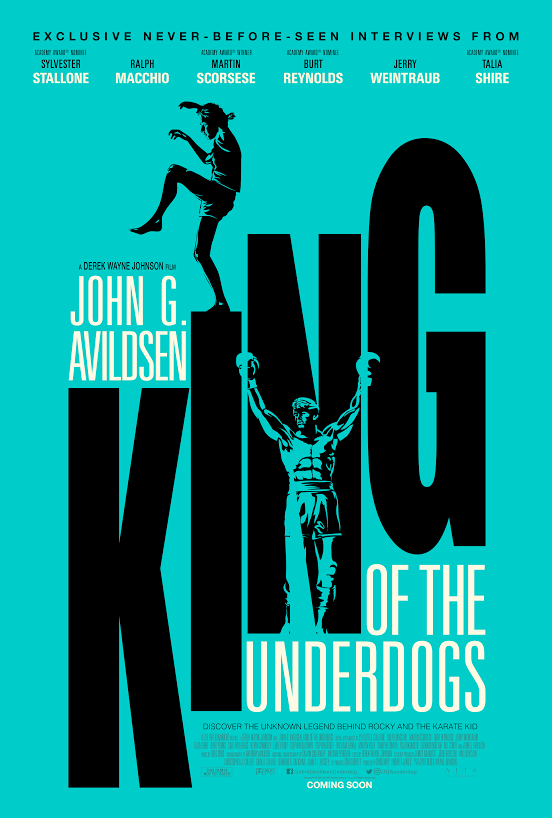

Joining Frank is filmmaker Derek Wayne Johnson whose film JOHN G. AVILDSEN KING OF THE UNDERDOGS premiered in February at the 32nd Santa Barbara International Film Festival. It is a fantastic film, chalked full of interviews with Sylvester Stallone, Martin Scorsese, Talia Shire, Ralph Macchio, Burt Young, Carl Weathers, Burt Reynolds, Bill Conti, and John Avildsen himself. Derek is currently going into production on his next two films, STALLONE: FRANK THAT IS and 40 YEARS OF ROCKY: THE BIRTH OF A CLASSIC. For those who tuned into our SBIFF podcast, you should remember my red carpet interview with Derek.

Joining Frank is filmmaker Derek Wayne Johnson whose film JOHN G. AVILDSEN KING OF THE UNDERDOGS premiered in February at the 32nd Santa Barbara International Film Festival. It is a fantastic film, chalked full of interviews with Sylvester Stallone, Martin Scorsese, Talia Shire, Ralph Macchio, Burt Young, Carl Weathers, Burt Reynolds, Bill Conti, and John Avildsen himself. Derek is currently going into production on his next two films, STALLONE: FRANK THAT IS and 40 YEARS OF ROCKY: THE BIRTH OF A CLASSIC. For those who tuned into our SBIFF podcast, you should remember my red carpet interview with Derek.

Podcasting Them Softly is extremely excited to present our conversation with critically acclaimed filmmaker

Podcasting Them Softly is extremely excited to present our conversation with critically acclaimed filmmaker