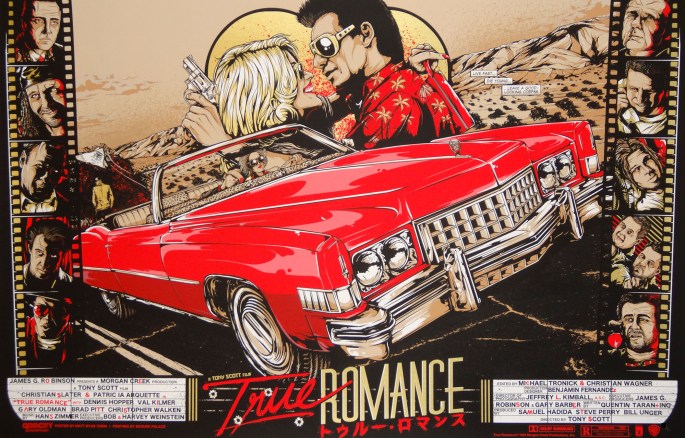

Roger Ebert hailed True Romance as a silly teenage boy’s fantasy come to life, fun and energetic, but absurd. I was a silly teenage boy the first time I saw the Director’s Cut of True Romance on DVD, and like some of my friends at the time, I loved it. I still feel like a silly teenager on the inside sometimes, and that part of me still loves watching this action packed piece of Hollywood entertainment. It might be silly, but that never bothered me before anyways.

True Romance requires a suspension of disbelief, to get your mind past the idea that in a single night, a young comic book store employee named Clarence with a love for Elvis and Sonny Chiba Kung-fu flicks, and the bombshell first time prostitute Alabama hired by Clarence’s boss to give Clarence a good time on his birthday, would ever fall so deeply, madly in love, that they marry the next morning after he kills her pimp, and then set out on a soon to be violent honeymoon with a bag full of cocaine that belongs to the mobsters hot on their tail. Although, this is a Quentin Tarantino screenplay, so most of this sounds like a slow drive to grandma’s house in Tarantino Land.

Christian Slater and Patricia Arquette star as Clarence and Alabama, respectively, the seemingly ideal cinematic couple. Sure, they’re both a little bit cuckoo when you look at the direction the narrative takes, you must be a bit wacko to get married within hours of meeting, but the natural chemistry between the two actors generates a palpable sensation of honest love oozing from Clarence and Alabama. You really feel the passion between them when they kiss and flirt with each other.

The rest of the cast is rounded out by a director’s wet dream of character actors, including Val Kilmer, Gary Oldman, Samuel L. Jackson, Brad Pitt, James Gandolfini, Christopher Walken, Michael Rappaport, Tom Sizemore, Christopher Penn, Bronson Pinchot, Saul Rubinek, and Dennis Hopper as the least crazy, perhaps even 100% normal character in the entire film. They all appear in one facet or another over the course of this ensemble piece, each adding their own unique stamp to the late Tony Scott’s coolest pure action movie. It’s a real pleasure seeing such a remarkable cast at the top of their game.

As strong as the two leads are, they just aren’t as good as my two favourite performances in True Romance, from Gary Oldman, and James Gandolfini. Oldman is almost obnoxiously over the top and nearly unrecognizable as Drexl Spivey, Alabama’s eccentric dead-eyed, scarred, dreadlocked pimp. In such a brief amount of screen time, he creates one of cinema’s most memorable movie villains, a nasty, vile, unpredictable psychopath.

The same can be said for Gandolfini as Coccotti’s underboss Virgil, a shotgun toting psycho in his own right, and the ultimate nightmare for the naive Alabama. He doesn’t get to say much, but what comes out of his mouth carries immeasurable contempt and cruelty, later witnessed physically manifested in his violent abuse of the strong willed Alabama. I genuinely felt afraid for her throughout their graphic struggle, despite my assumption she would eventually overcome Virgil in brutal fashion anyways. Gandolfini was always just that damn good.

Much has been made about the most popular sequence in the film, largely referred to as “the Sicilian scene”, a long conversation between Walken’s Don Vincent Coccotti, whose drugs Clarence and Alabama currently have in their possession, and Hopper’s Clifford, a former cop and Clarence’s estranged father. The popularity of the scene derives in part from the verbal duel between Coccotti and Clifford, which leads to one of the funniest moments in any film Tarantino had his hands on, invoking a big ole belly laugh for those open to the crude and otherwise offensive humour of the scene. It’s my favourite dialogue driven scene in the film, always captivating me with Tarantino’s linguistic flair, and the sharp delivery of the now classic lines by Walken and Hopper. Every single time I watch True Romance and Hopper says “You’re part eggplant.” to which Walken retorts, “You’re a cantaloupe.”, I laugh out loud, and hard.

And then of course, there’s the action. Fast, furious, brutal, and unflinching, the slew of volatile outbursts of stylish, balletic violence are both dazzling and brutal in the same breath, a hypnotic flurry of blood and death. As a teenager, I was completely blown away by just how violent and intense the imagery was. Even today I sometimes find myself picking my jaw off the floor after the infamous bloody final shootout, which you have to see to believe. Tony Scott directed the hell out of those action pieces, and it’s a joy to see their influence running rampant in today’s films.

When you analyze True Romance, the harder and deeper you look, the more likely you might be to find cracks in the foundation; it’s not the flawless masterpiece some might hope for. But if you take True Romance for what it is, a piece of entertainment, and you choose to view it on a superficial level only, you probably won’t find any cracks at all. Not every film has to be perfect to be great entertainment.

“You’re so cool. You’re so cool.”

Podcasting Them Softly is honored to present a chat with actor

Podcasting Them Softly is honored to present a chat with actor